The App Store had just turned one when, sometime in the summer of 2009, concept artist and game developer Zach Gage published a preview video for an iPhone game he had been working on. The game was based on a simple premise: Gage’s girlfriend liked playing Tetris for iPhone, which he thought was a rushed adaptation of the console game that didn’t take advantage of the iPhone’s unique hardware. “I just looked at it”, Gage told me in an interview on our podcast AppStories, “and I thought – I can make a better game than this”. So, in his spare time between different projects, he got to work.

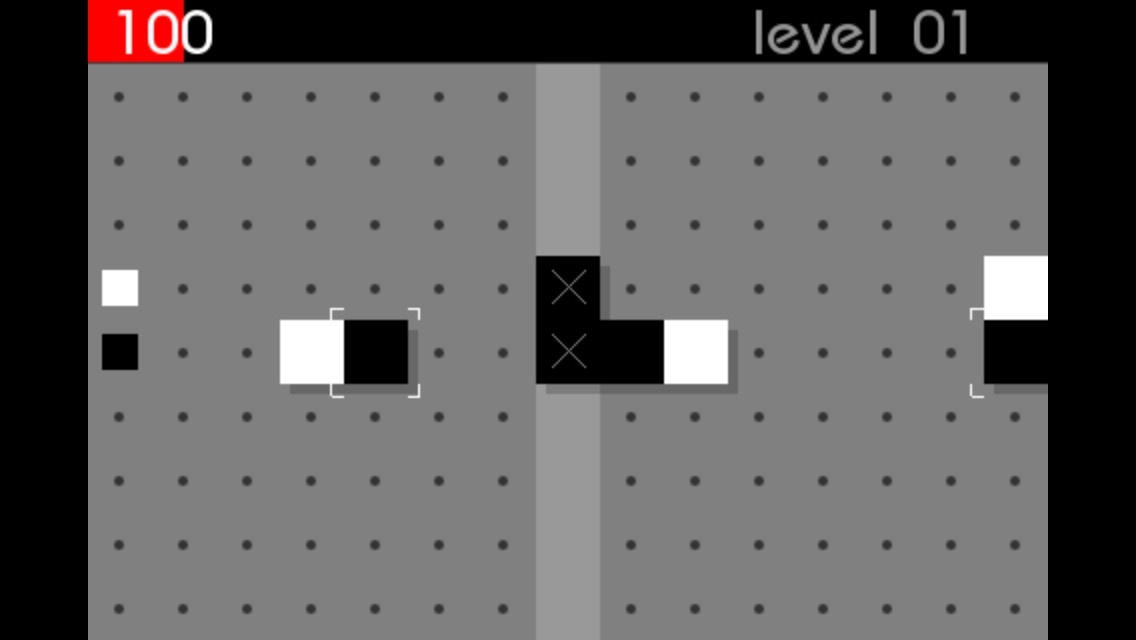

The game, which launched in fall 2009, was called Unify. On his website, Gage described it as “Touch-Tetris for both sides of the brain”. In Unify you can see traits that would define Gage’s later work on the App Store: the game takes a well-known concept and adds a twist to it – blocks come in from both sides of the screen rather than falling from the top as in classic Tetris. Graphics are minimal, but instantly recognizable and somewhat cute in their simplicity. Unify is entirely controlled via touch, eschewing any kind of console-like onscreen controls. “I was trying to imagine what Tetris would look like as a game designed for multitouch”, Gage added. “And that kind of got me hooked. After that, I just kept making games”.

Unify has all the elements for an ideal App Store origin story: a basic preview video uploaded to Vimeo 9 years ago, before YouTube became the de-facto standard for videogame trailers; an independent artist and game developer who, years later, would win awards for innovation in mobile gaming; a funny backstory that stems from big publishers’ inability to adapt console games to touchscreens a decade ago.

You’d think that Unify would make for the perfect case study in app development and mobile creativity, if only for historic purposes. Except that Unify is gone from the App Store, as if it never existed in the first place.

If you were to look at the App Store’s developer page for Zach Gage – who worked on the award-winning Ridiculous Fishing, released indie breakthroughs such as Really Bad Chess and Flipflop Solitaire, and was even profiled in an App Store story by Apple – you’d see 2016’s Sage Solitaire as his App Store debut. Unless you still have an old iPhone that was never updated to iOS 11, Gage’s early work isn’t playable anymore. All that remains are old reviews on gaming blogs, awkward gameplay videos recorded before YouTube Let’s Plays, and our memories.

The story of Unify is emblematic of a bigger change on the App Store, one which is considered by some a problem at a cultural level, and which others simply ascribe to the evolution of the App Store as a digital marketplace.

For the past two years under Phil Schiller’s tenure, Apple has been cleaning up the App Store, ridding it of spam and clone apps, outdated and abandoned software, and other categories of apps that the company doesn’t see fit for the platform anymore. Unify and thousands of other older iOS apps and games were “purged” as part of Apple’s crackdown on 32-bit legacy software: with iOS 11 last year, the company began preventing apps that hadn’t been updated for 64-bit devices from being launched altogether, thus rendering 32-bit apps that were still installed on users’ devices useless.

During this process, Apple didn’t forcibly remove 32-bit apps from the App Store; they just made them non-installable for users, showing a message on the product page that explained why an app couldn’t be downloaded anymore. However, to avoid explaining to customers why an app could only be installed on an older device running iOS 10, several developers simply went ahead and removed their apps from the App Store as they had no intention of updating them anymore. Others, like Gage, just left older “lite” (i.e. free) versions on the Store. As a result of this technical cleanup, the App Store shrunk for the first time in 2017; according to stats shared by analytics firm Appfigures, around 100,000 apps (out of two million) were “lost” between October 2016 and late 2017.

Very few people would be sad that their favorite fart app from 2008 was never updated for 64-bit and got nuked by iOS 11, but the same isn’t true for pioneering titles that were essential in writing the history of the App Store. And while the topic of software preservation has been addressed by other industries, Apple has largely ignored this conversation, treating all apps as equal commodities in spite of the fundamental role that some of them played in the history of the App Store, the art of gameplay design, and, ultimately, our culture.

On the tenth anniversary of the App Store, and looking ahead to the App Store’s next 10 years, this feels like a discussion worth having.

Update Culture

“Digital preservation” often gets thrown around as an esoteric concept only activists care about, but the reality is much simpler: as Wikipedia neatly sums up, digital preservation is the practice of ensuring that “digital information of continuing value remains accessible and usable”.

Certain historians strive to preserve precious manuscripts and old books; digital archivists have poured years of effort into allowing notable pieces of software to stand the tests of time. But while conserving analog documents and artifacts mostly concerns the physical aspects of degradation and preservation (that is, ensuring that paper can survive multiple centuries or that libraries don’t burn down), preserving software involves trickier challenges, from ever-changing technical standards and programming languages to legal hurdles that may range from copyright disputes to new legislation. The intangibility of software is its biggest strength in our everyday usage of apps, web services, and games: they can easily be available anywhere, at any time. From a preservation standpoint though, this can also be their weakest point of failure.

In this scenario, the App Store is squarely at odds with any software preservation effort because of how Apple structured it 10 years ago and operates it to this day.

First and foremost, even though Apple didn’t invent the idea of a digital marketplace that manages users’ purchases and periodic software updates, the App Store established a superior framework for others to copy; with over two million apps available for users to download, the App Store epitomizes modern digital distribution at scale. It’s undeniable that the App Store has influenced, if not directly shaped, the digital shopping experiences of the likes of Google, Microsoft, Sony, and Nintendo. One of the App Store’s core principles, which we take for granted today, is the fact that every app you download is but a version of it from a specific point in time.

Unlike, say, the SNES cartridge for 1992’s Super Mario Kart or a Street Fighter arcade cabinet from the late 80’s, an app is a constantly evolving product that changes rapidly over time across multiple versions to support different devices, introduce new features, or alter gameplay mechanics. While videogame companies still straddle the line of selling physical copies of games that often require digital patches and updates, the App Store never offered physical counterparts of apps to begin with. To “preserve an app” begs the fundamental question of which iteration of it should be archived for posterity, and who should be in charge of doing so.

Alongside this approach is Apple’s relentless push for new technologies, which has forced the company to regularly increase the compatibility threshold for apps to receive updates or remain on the App Store. Over the past 10 years, Apple has often tied new app requirements to new hardware, features of specific devices, or OS updates. In a way, the App Store is a digital representation of Apple’s evolving product line.

In 2012, for example, Apple required new app submissions to include Retina screenshots in their App Store product pages, pushing developers to support the high-resolution display of the iPhone 4, which came out in 2010. The following year in December, Apple required both new apps and app updates submitted to the App Store to be built with the latest version of Xcode and support iOS 7, a sweeping redesign of the OS that launched to the public in September. A year later, the company told developers they would require new apps to be compiled for iOS 8 and include 64-bit support by February 2015; a few months later, they confirmed that existing apps also needed to support 64-bit architectures by June 1, 2015 if they wanted to receive future updates. The iPhone 5s, the first iPhone to deliver a 64-bit SoC, had come out two years prior in 2013.

Between 2016 and last year, Apple announced a major App Store cleanup initiative to get rid of outdated apps and, following numerous warnings, the company completely dropped support for legacy 32-bit apps. Just this year, Apple started requiring new apps submitted to the App Store to be built for iOS 11 and support the iPhone X’s Super Retina display, including Universal apps; sometime later this month, app updates submitted to the App Store will have to comply to the same requirements.

It’s important to note that Apple’s approach, although justified by the fast innovation pace of mobile devices and a commitment to provide a great App Store experience to customers, has created the modern expectation of downloading an app once and thinking it’ll be supported forever. Think about it: how many times have you heard from a friend or relative who bought an app four years ago and was upset that it eventually stopped working?

The “update culture” that permeates our digital lives today – which has been accelerated by smartphones – has long clashed with the economic realities app makers face every day. For years, while Apple was asking developers to keep updating their apps to support new versions of iOS or new display resolutions, they weren’t giving them enough tools to turn apps into sustainable businesses that could justify ongoing development throughout the years.

There’s a (New) App for That

The App Store never supported free trials in the traditional sense, and In-App Purchases have never been a great solution for business models based on recurring revenue. Apple only opened up auto-renewing subscriptions to developers in 2016 – long after app makers had been lamenting the burden of supporting an app forever while failing to make money off of it across several years. As a result, while subscriptions are allowing more developers to support the same app over time today (with free trials now officially part of the same system too), the App Store wasn’t always like this, which creates a fundamental problem when debating mobile app preservation.

To compensate for the lack of flexible purchase mechanisms in the early days of the App Store, developers came up with an idea: instead of having to update an app forever without getting paid for it, they could just release a major update as a brand new, separate version on the App Store and charge for it again. The technique was allowed by Apple and it’d give developers an alternative to upgrade pricing, another common strategy of the shareware world that was never translated to the App Store’s new economy.

Tweetie, a groundbreaking Twitter client created in 2008 by Loren Brichter, is widely regarded as the pioneer of this concept: when Brichter was ready to release version 2.0 of the app in late 2009, he decided to sell it as a separate, paid upfront app on the Store. The decision was controversial at the time, but became common practice in the indie developer community in the intervening years: from Reeder and OmniFocus to Tweetbot and Fantastical, hundreds of developers of high-profile apps – utilities that Apple also celebrated with Design Awards – opted for selling major updates as new SKUs, eventually phasing out old versions after an initial grace period. For developers who don’t want to use In-App Purchases or subscriptions, this is still the easiest way to ensure the “same” app can be profitable over time.

This way of selling software on the App Store has enabled several solo developers and small shops to keep producing apps, but it has also substantially complicated the discussion on whether apps (i.e. non-game apps) ought to be preserved, and if that could even be possible. When we think of preservation, we generally think of museums, which collect and conserve artwork or tools that still exist. Apps are nothing like that: not only are they digital, but they are often updated with changes that alter their original functionality or prevent them from running on modern hardware. When you visit the Louvre, you don’t have to worry about which version of the Mona Lisa you’re looking at; when physical artwork requires actual changes, those who work in restoration strive to be as close to the original version as possible (at least most of the time). If we were to preserve the original Tweetie or one of Apple’s legacy iOS apps, which version of those apps should we try to immortalize in time? Perhaps all of them? And if, thirty years from now, someone decides to offer the equivalent of the Internet Archive’s Classic Macintosh Software Library but for iOS apps, will they ever be able to retrieve all versions of apps that were pulled by developers from the App Store to make room for new SKUs? Would old versions even work at all?

The answer, as things stand today, is likely “no”. Apple has never addressed preservation of old apps, nor have they ever offered tools to emulate old apps or download specific releases from the App Store’s servers. The Internet Archive’s Classic MacOS library features 127 titles between applications and games; the App Store launched to 552 apps on day one 10 years ago and now features over 2 million. Unless Apple invests serious time and effort into preserving the history of app updates and apps that are no longer on the App Store, it’ll be extremely difficult for anyone to even preserve a small segment of the App Store’s catalog for future interaction and archival purposes. Whether created by big companies or indie developers, apps tend to be disposable utilities that are updated too frequently, are often removed from the App Store for financial or technical reasons, and run on a closed-source, signed firmware that can only be installed on Apple devices. To think that, decades from now, the entire history of the App Store will be preserved is a straight-up utopia.

But perhaps there is a way to reconcile the traditional preservation that occurs in museums and libraries with cataloguing and archiving the history of the App Store. Museums do not necessarily preserve every single object that was ever produced in human history. They research, select, and preserve a subset of valuable items. They curate. This is what the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) does all the time, and it’s exactly how they approached digital preservation of games for their Applied Design exhibition, which ran from March 2013 to January 2014.

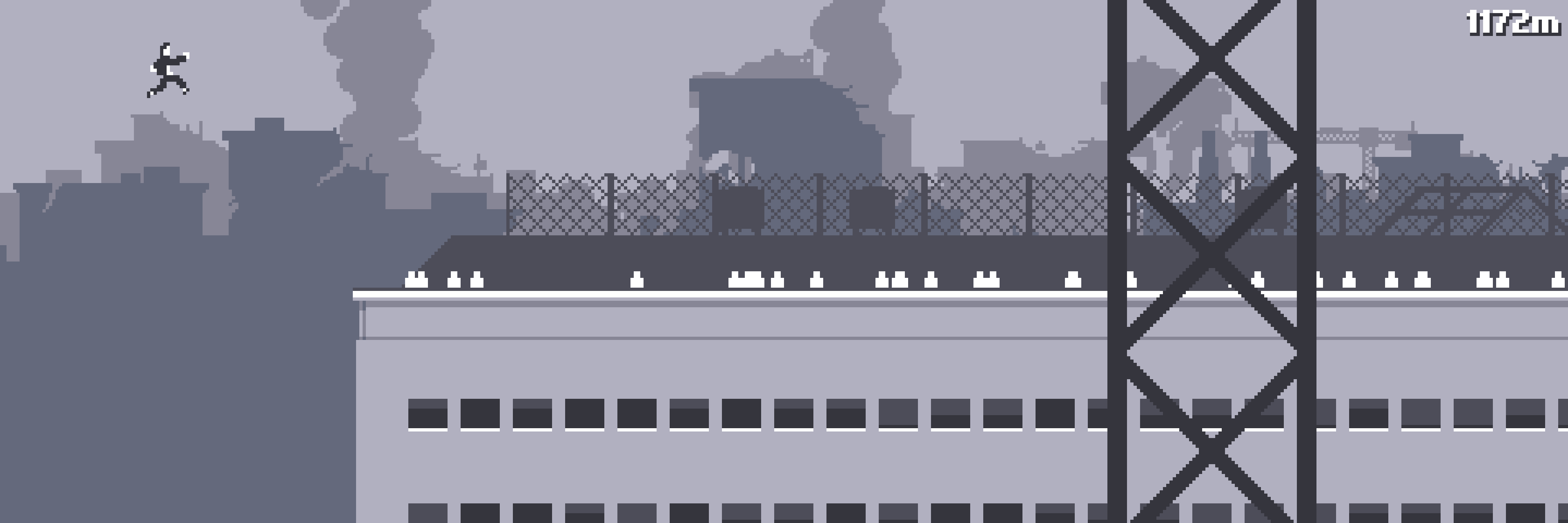

In late 2012, Paola Antonelli, Senior Curator at MoMA’s Department of Architecture and Design, announced that the museum acquired a selection of 14 videogames which, like other objects in MoMA’s collection, offered a “combination of historical and cultural relevance, aesthetic expression, functional and structural soundness, innovative approaches to technology and behavior, and a successful synthesis of materials and techniques in achieving the goal set by the initial program”. Games featured in the initial collection included classics such as Pac-Man and Tetris but also bold audiovisual experiments like vib-ribbon and flOW, simulations like The Sims and SimCity 2000, and even the infinite runner Canabalt, at the time widely known as an iPhone game.

Besides the decision to treat videogames as culturally relevant design artifacts, the MoMA’s strategy for preservation was fascinating as well. For starters, the museum’s digital conservation team obtained copies of the original software (whether on cartridge or disc) and hardware. Then, they sought to acquire the source code of games in the collection as a backup and, whenever possible, corroborating technical documentation with annotated reports of a game’s code from its creators. Given the different nature of each game, from the immediate gameplay of Katamari Damacy to the multiplayer world of EVE Online, the MoMA created ad-hoc demos or guided tours to allow visitors to experience the game and understand its design in just a few minutes. If necessary, they recreated the “essence” of a game while staying true to its original assets and mechanics.

I was able to talk to Paul Galloway, Collection Specialist at MoMA’s Department of Architecture and Design, about their Applied Design exhibition and the museum’s approach to software preservation. “This is a very large subject, and one to which we are devoting a lot of resources”, Galloway told me over email. “We are committed to preserving any work of software that comes into MoMA’s collection, whether that is a website, an app, or a video game”, he added.

Of course, given the abundance of interesting digital content available on the web and mobile app stores today, the MoMA had to update their conservation strategies accordingly. “Preserving a video game from the 1980s is very different than preserving an artistic interactive installation or a website from 2018”, Galloway noted in our conversation. “We select works for the collection in the same way we select paintings or any other artwork – very carefully and with great deliberation”.

If MoMA, an organization with more resources and prestige than any other hobbyist conservation effort, recognizes the challenges of digital preservation and has opted for a more selective and deliberate approach, perhaps attempting to preserve every version of every app ever released is indeed a foolish proposition. Maybe archiving and preserving the history of the App Store should follow the same principles as the MoMA: going forward, we should find ways to curate and establish practices to save a limited selection of titles that are representative of human creativity and interaction design as expressed through touch screens.

As it turns out, these are the same considerations a lot of folks in the videogame industry has been pondering for a long time.

A Link to the Past

The videogame industry as we know it has been around for over four decades at this point, and it’s easy to understand why videogame companies big and small are increasingly thinking of new solutions to preserve their history. The nostalgia effect in gamers who were kids in the golden days of Atari consoles, the NES, and the SEGA-Nintendo console wars is a proven revenue generator; even today, despite their archaic graphics and trite plots, the fun of old games can be timeless. For game publishers, re-issuing an old title on a modern console often feels like a “free money” opportunity – ask Nintendo, who has long been criticized for re-releasing Super Mario Bros. on multiple iterations of its Virtual Console over the years, only to announce yet another old game emulation service launching later this year. The older the videogame industry grows, the more it looks inward, turning nostalgia into easy cash flow.

When we think of preserving old console games, we think of Nintendo’s aforementioned (and fragmented) Virtual Console efforts, or perhaps Nintendo’s relatively new Classic Edition line of small retro consoles, unofficial emulators developed by enterprising fans, or maybe the collections that companies such as Namco, Capcom, or SEGA have released over the past several years as standalone playable compendiums. For the most part though, these initiatives are about emulation and giving players a legal way to replay old titles. Digital Eclipse believes that true preservation of the medium requires a deeper commitment and painstaking study of games’ history.

Reopened as an independent entity in 2015 after being spun off from Backbone Entertainment, Digital Eclipse is an American videogame studio whose mission is to preserve classic games by doing something more than just packaging them into basic emulators. Founded by Mike Mika, Frank Cifaldi, and Andrew Ayre, Digital Eclipse has specialized in creating meticulous anthologies of popular games that, in addition to faithfully representing how games might have looked on CRT monitors, feature “digital museums” filled with concept artwork and development notebooks, special challenge modes, soundtracks, and other previously unreleased memorabilia that pay homage to the historical nature of a game and properly contextualize it.

The studio’s most recent release is Street Fighter 30th Anniversary Collection, a collection of 12 classic titles that includes archival documents from Capcom (the creators of the series), music files, and lots of historical details about the franchise. Digital Eclipse’s first 2015 work, Mega Man Legacy Collection, pioneered this approach: in addition to six original Mega Man games, the compilation featured stage remixes in a new Challenge Mode with online leaderboards, a Rewind option to reverse gameplay, plus a Museum Mode with rare concept art and original promotional materials. If it sounds like the videogame version of the Criterion Collection for films, it’s because this is exactly what Digital Eclipse is trying to achieve. For their upcoming SNK 40th Anniversary Collection, set to be released in November, the company has even found a way to emulate the peculiar rotary joysticks from SNK’s arcade days through the Nintendo Switch’s dual-analog sticks. It’s just another example of Digital Eclipse’s mantra that games are more than just playable code, “they’re also a snapshot of a time and a place”.

Besides the cultural aspect of Digital Eclipse’s effort to preserve artistic intent while also making games more palatable for a modern audience, what they’re doing from a technical standpoint is fascinating, and a model worth keeping in mind for the future of iOS game preservation.

As Digital Eclipse’ Head of Restoration Frank Cifaldi noted in a 2015 interview, most companies that keep porting old games to new systems often need to start the process over whenever a new console architecture comes around. This costs time and money, and typically results in cheap ports that aren’t faithful to the original game or do nothing to explain its history. To overcome this problem, Digital Eclipse has developed a custom engine (aptly named the Eclipse Engine) that can be easily ported to multiple platforms and act as a middleground format for old games. As long as a game can run in the Eclipse Engine, it’ll run on any platform where Eclipse is supported, be it PlayStation, PC, Xbox, or Switch. “Once a game is converted to our Eclipse format, it will run anywhere Eclipse does”, Digital Eclipse plainly states on their website.1

It’s interesting to consider how the Digital Eclipse approach may become a template for others to follow decades from now, when videogame historians of 2040 will look back at early iPhone games and wonder how they can be emulated and contextualized. This may seem like an odd prospect now – does the iPhone even have games as important or celebrated by the industry as Mega Man or Street Fighter? – but keep this in mind: kids playing iOS games today will grow up and look back fondly at their earliest videogame memories just like many of us reminisce about our old SNES, Genesis, or Game Boy consoles. Mobile game nostalgia sounds like an absurd scenario now, but if history is any indication, it will happen, and it’ll involve an entire generation of young players whose only experience with videogames growing up was an iPhone or iPad. Collecting historical materials about the App Store’s first decade of games (in today’s world, these would be YouTube videos, tweets, and blog reviews) and combining them with a middleground engine to bring back games on multiple platforms could be an intriguing bet to preserve the medium’s origins and history.

Digital Eclipse, however, isn’t the only company thinking deeply about game preservation and giving us a glimpse at what could be done to preserve the App Store’s gaming history going forward.

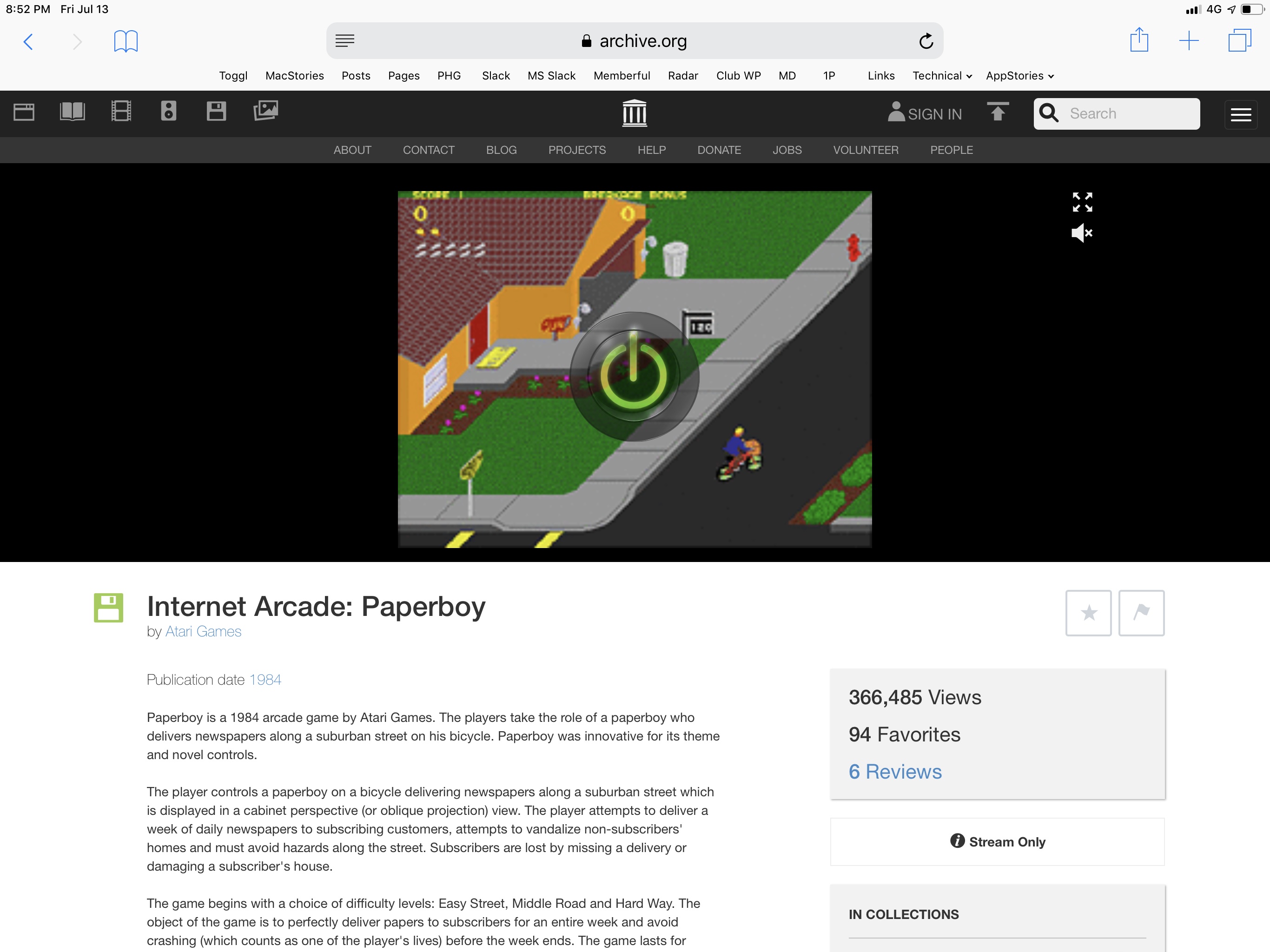

In a GDC talk from 2015, Jason Scott, archivist at the Internet Archive, made the case for games being artifacts with historical value, which developers need to start preserving today. The Internet Archive, along with preserving games and software, works to preserve books, films, websites, magazines, and other media, putting everything on the open web for others to see and use.

One of the Internet Archive’s fundamental beliefs, Scott said in his presentation, is that “access drives preservation”. This is the idea behind The Internet Arcade, the non-profit free emulator of classic games that now features over 1,700 titles that can be played by anyone in a browser tab. Whether it’s Joust, Out Run, Defender, or the evergreen Paperboy, if you remember a coin-operated game from the 80s, chances are you’ll find it again, freely available on the web, emulated on The Internet Arcade.

It’s hard to imagine Apple teaming up with The Internet Archive in 40 years to celebrate the App Store’s 50th anniversary with mobile games emulated in browser tabs2, but the idea of streaming games from a server without having to run them locally on your device isn’t so crazy once you realize a handful of companies are already doing it today. Sony’s PlayStation Now, for instance, lets players stream a library of PS4, PS3, and PS2 games for a monthly fee, with no local downloads and cross-platform support for PS4 and PC; even Google is rumored to be entering this space with a cloud gaming product to allow anyone to play console-quality games in the browser. If Apple ever adopts streaming in the future, it could potentially offer a way to play classic iPhone games without the complication of running old versions of iOS or owning 32-bit devices.

If the App Store goes through more cleanup events for “legacy” titles in the next 10-20 years (at some point, it seems inevitable that the current 64-bit games will become legacy software on Apple platforms), another idea Apple could borrow from the videogame industry is backwards compatibility.

The concept is simple in theory, but trickier to pull off in practice: in the history of videogame consoles, some of them have offered a compatibility mode to play titles from the previous console on the current one. The PlayStation 2, for instance, offered backwards compatibility with PlayStation games, as did the Wii with the GameCube and the Wii U with the Wii; Nintendo’s Game Boy titles could be played on the Game Boy Advance, which in turn was compatible with the DS, which was compatible with the 3DS later on. You get the idea.

By embedding an emulator for an older generation into the latest system, console makers have often relied on backwards compatibility to artificially inflate a console’s launch catalogue, cater to an existing user base, and spread goodwill among customers. Those who follow videogame news may be familiar with fan reactions to Microsoft’s announcement of Xbox One’s backwards compatibility with Xbox 360 titles at E3 2015.

Here’s the kicker though: Apple has been offering a backwards compatibility mode on iOS for years now – sort of. When the iPad launched in 2010, Apple decided to let the new device run existing iPhone apps out of the box in a virtualized environment. At the time, the idea was that the iPad was a nascent platform, so if a user’s favorite app was not available for iPad yet, they could install the iPhone version and run it on the big screen. Eight years later, the feature is somehow still available and actually being improved in iOS 12 with support for iPhone 6-display resolutions while in compatibility mode. When another major shift in Apple’s platforms occurs within the next two decades, it wouldn’t be unreasonable to envision a compatibility layer3 that ensures iOS apps and games can continue to run natively and be usable on a new architecture. However, I wouldn’t count on Apple going as far as enhancing old games for 4K resolutions like Microsoft is doing for Xbox 360 games running on Xbox One X hardware. If and when Apple’s mobile devices grow into something radically new, I expect Apple’s take on “backwards compatibility” to be an emulation layer that preserves millions of iOS apps and games for the new system.

If we follow the idea that access drives preservation, we should then consider how the lack of App Store exclusivity of popular games might also turn out to be a good thing for everyone years from now.

In recent years, particularly thanks to the availability of cross-platform game engines such as Unity, we’ve seen high-profile titles launch on iOS first and later expand to consoles or PCs. The Room, a popular puzzle game by Fireproof Games, launched on iOS in 2012 and was ported to Windows in 2014; Monument Valley and Hidden Folks, two award-winning iOS games (Monument Valley 2 was introduced as an exclusive at WWDC 2017), can also be found on Steam, Google Play, and Amazon; Bethesda’s Fallout Shelter, a free-to-play simulation spin-off of the Fallout series, launched on iOS in June 2015 and was then ported to Android, Windows, Xbox One, PlayStation 4, and Nintendo Switch.

We’re now at the point where, unless it’s technically impossible for a development studio to adapt an iOS game to other platforms, cross-platform engines and the availability of other digital game stores make it dramatically easy to extract more revenue from the same game by bringing it to the console and PC markets. While having a game on other digital stores isn’t in itself a preservation guarantee4, it does increase the chances that a game will survive in some form over the next decades. Perhaps some of these may even receive the printed copy treatment by companies such as Limited Run Games, which specializes in making physical versions of games that were originally digital-only.5

The videogame industry has far from solved the preservation dilemma, which is an ongoing debate that requires game developers to take preemptive measures to ensure their creations – arguably, digital works of art – can be preserved and enjoyed for decades to come. Like any industry that needed to grow up too quickly to match the fast-paced technological progress of the past 20 years, the game industry had its fair share of missteps that should be valuable lessons for mobile developers thinking about the future of their games today. But at least more videogame companies are thinking about preserving their history to make sure blunders such as the SatellaView and its lost games are the exception, not the rule. Even though it’s a constant challenge, topics such as digital conservation, emulation, and backwards compatibility are being discussed in the videogame industry and taken more seriously than ever before.

The same can’t be said about the App Store, which has already lost hundreds of games to the inexorable marching of time and expiring contracts in its first decade. The biggest problem facing App Store preservation today is the lack of any kind of emulation for old 32-bit titles that are no longer supported on modern hardware. Those games are confined to the physical storage of old devices that haven’t been updated to the latest OS. As MoMA’s Paul Galloway told me, “all born-digital works have a number of hardware and software dependencies that must be met in order to work”. From this perspective, the problems faced by apps on mobile OSes are common to many other kinds of digital works. But there’s an important difference. “[While] there is a large community dedicated to projects like MAME and other emulation tools”, Galloway added, “there is not yet an equivalent established for games designed for mobile OSes. Our Media Conservation team is thus tasked with figuring out how to bridge this gap”.

The first ten years of the App Store are littered with stories of games that were played and loved by millions, only to eventually disappear because of technical or legal reasons. Scroll back through your App Store’s Purchased history and you’ll come across some familiar names: Tap Tap Revenge, one of the iPhone’s launch titles; the Rolando series; the classic and beloved Flight Control; the iOS port of the original Bioshock; DoubleFine’s Dropchord; and many, many others such as Toki Tori, Minigore, the first Real Racing, Astronut, Super Stickman Golf, LostWinds, and more.

Browsing these old lists shows us how far the iPhone and the App Store have advanced in the span of 10 years, but it’s also a sad reminder that we can no longer play a sizable portion of games that pioneered iPhone gaming at a moment in time when nobody knew how to design for multitouch controls. For millions of people, early iPhone games represent their first cherished videogame memories, and many of those games are just…gone.

Lost to History

Looking ahead to the App Store in 2030 or 2040, the issue of preserving existing apps and games will become increasingly pressing both for Apple and third-party developers.

As I outlined in this story, the videogame industry is a good starting point when debating software preservation: there are several parallels with the App Store (including the new Games as a Service trend, which is essentially what some apps are trying with subscriptions) and game developers have been thinking about digital conservation for longer. Besides cultural initiatives such as the MoMA, and assuming that companies such as Digital Eclipse and Limited Run will continue to be more suitable for games than apps, backwards compatibility and emulation seem like the best ideas that the App Store could “steal” from the videogame industry over the next couple of decades.

“I wish that Apple would go the route of emulation”, Zach Gage told me in our interview on AppStories. “On some level I’m a little bit comfortable that [my older games] are gone because I wouldn’t necessarily want people going and buying them because I don’t feel like they’re really representing the level of polish and the kind of output that I have now”, Gage added. This is an interesting point as it raises the question of whether an app’s original creator would even want their creation to be preserved forever. “But also I do feel like there’s a real value in terms of just being able to see the history of someone’s work. And it makes me sad that my early games are not available to be played anymore”, he concluded.

Gage also noted that, unlike with his first iPhone games from 2009 and 2010, he’s trying to make his newer titles more “protected” in terms of being easily recompiled or being released on other platforms. He even mentioned that perhaps in the future someone could use one of the many iOS piracy websites (where people can download illegal cracked copies of apps and and games for free) as repositories for emulators of old titles given that those sites are, effectively, the only public archive of older iOS app binaries. As crazy as it sounds, he’s not wrong.

Emulation isn’t perfect though. As the developers at Digital Eclipse noted years ago, emulation doesn’t put games in the historical context and most companies only do a passable job at adapting old titles for the latest systems. “Emulation is a good basic place to start, as it does preserve the works in a basic, reliable way”, MoMA’s Paul Galloway told me. “There are some works for which the lack of original hardware would adversely affect the understanding of the game”, he added, mentioning Duck Hunt for the NES as an example. “Something is certainly lost without the hardware, but the degree to which that really matters varies greatly from work to work”, Galloway said.

While it may get a bad rap among those who care about the art and craft of high-fidelity preservation, an emulation layer for old apps could be the simplest, cheapest, and most practical solution for Apple to preserve the App Store’s catalogue going forward. And although some apps and games may just stop working on their own eventually6, at the very least Apple should allow users to redownload and open those apps, even if they don’t take advantage of the latest and greatest features of iOS. The company’s decision to cut off support for hundreds of games that could still be enjoyed by customers with last year’s iOS 11 update is perplexing, and it raises doubts as to what might happen when the next major platform transition occurs. Would it really be in the best interests of customers to keep ridding the App Store of old apps and games that could still continue to work if only Apple offered a basic backwards compatibility feature?

Ultimately, this entire discussion goes back to a fundamental question: does it even matter to preserve old apps for posterity?

Software preservation is a sprawling and complex subject that is impossible to sum up in one short answer. This is why I wanted to round out our special App Store 10th Anniversary coverage by analyzing some of the different sides of software preservation. I don’t think there is one right way to handle conservation of old apps and games: I sympathize with Digital Eclipse’s meticulous approach, but I also applaud the MoMA’s efforts and what the Internet Archive is doing with emulation. I’m perplexed by Apple’s unwillingness to offer an emulation tool, especially for old iOS games, but I understand that the size of the App Store and the fast evolution of iOS are problems Nintendo and others didn’t have to account for 30 years ago. In many ways, preservation of mobile software is still uncharted territory.

I do believe, however, that we should be asking ourselves whether or not the apps and games we download on our phones each day are a reflection of society at a certain point in time that could be worth saving for the future. Personally, I think many of them are: today more than ever, apps are informing and shaping our culture through communication, entertainment, and news; mobile games are increasingly shedding the negative connotation of “mobile” and being discussed on equal footing with their console counterparts. And yet, despite capturing the cultural zeitgeist and being at the center of our digital lives, apps are still largely an ephemeral medium, deeply tied to ever-changing technology companies that seemingly don’t care about their past – only what’s next.

It doesn’t have to be this way. I want to believe that, over the next decade, Apple and third-party developers will learn to appreciate the history of the App Store. And that they will treat its back catalogue as something more than a nuisance with an expiration date. Because sometimes it can be useful, and perhaps even fun, to marvel at how far we’ve come by looking back at how it all began.

Let’s check back in 10 years.

- I highly recommend watching Cifaldi’s GDC 2016 talk on YouTube to understand his company’s mission. ↩︎

- Follow-up due in 2058 here on MacStories. ↩︎

- Rosetta, anyone? ↩︎

- Online digital stores get shut down and disappear too, as was the case with Nintendo’s old WiiWare line of games. ↩︎

- For more on Limited Run Games, I recommend listening to this interview on the Retronauts podcast. ↩︎

- For example, because the web services they are based upon stop working, just like it happened with old Twitter clients when the old Twitter API was retired. ↩︎