At WWDC 2015, Apple announced app search, a new feature of iOS 9 that will help users find content inside apps. Beyond the user-facing aspects of a new search page on iOS and proactive suggestions from Siri, however, lies a commitment to fundamentally rethink iOS’ relationship with apps and the web, with deep implications for the future.

With iOS 9, Apple wants to reimagine how information from apps is exposed to users. For a long time, iOS apps have largely been treated as data silos – utilities that kept gaining design improvements and powerful functionalities as iOS grew, but ultimately unable to bring their data outside the confines of their sandbox. Following in the footsteps of iOS 8’s adoption of extensions, Apple’s plan to further open up iOS is deceptively simple: just let users search for what they need.

Behind the scenes, the reality of iOS 9 search is going to be a little more complex than that.

Search

According to a study mentioned by Apple at WWDC, 86% of mobile users spend their time in native apps instead of the web. While this survey isn’t indicative of the global iOS user base and besides the fact that most apps do offer web views or are heavily web-based, this is a strong indication of the fact that native apps provide advantages that users appreciate, but they aren’t nearly as flexible as the web when it comes to retrieving information. This is a problem that I’ve covered multiple times in the past and that Google has been trying to fix with App Indexing for Android (and, most recently, iOS as well). There’s a vast library of information inside apps that could be offered to users to make them use (and enjoy) apps even more.

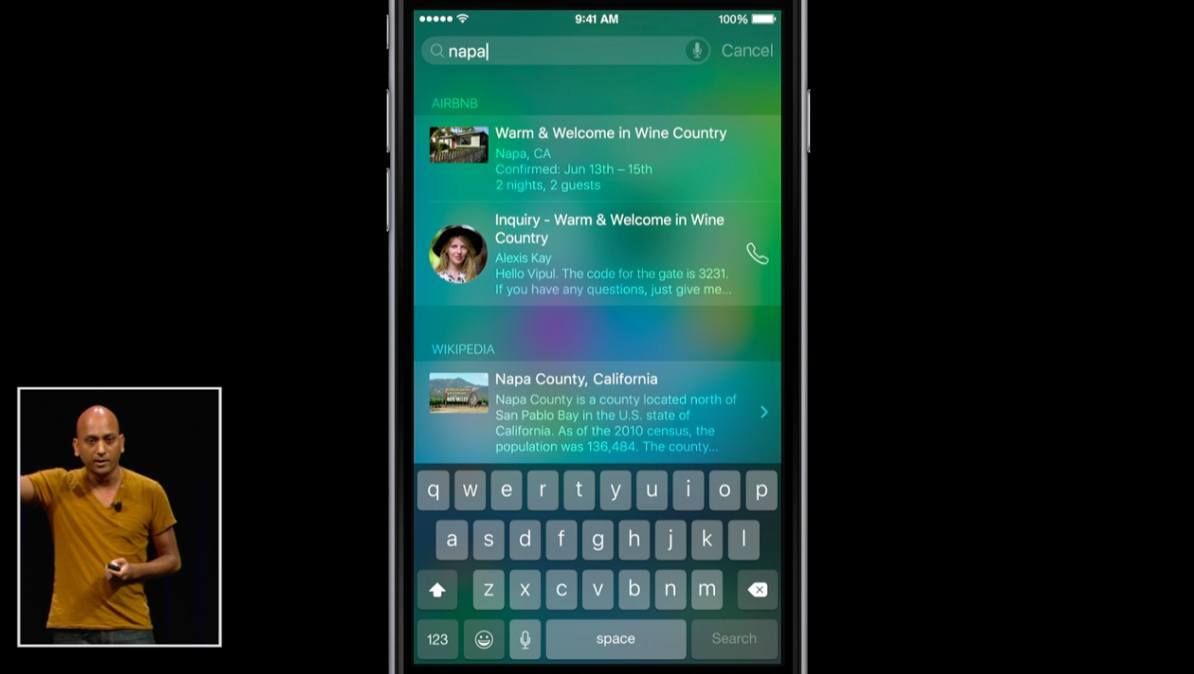

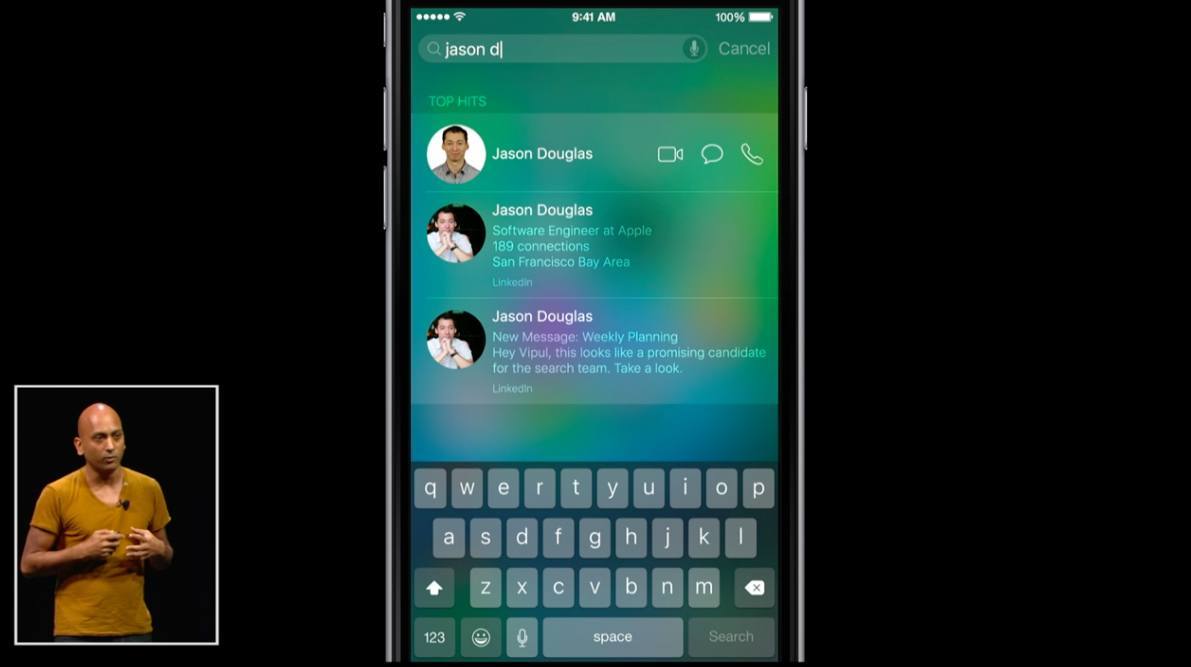

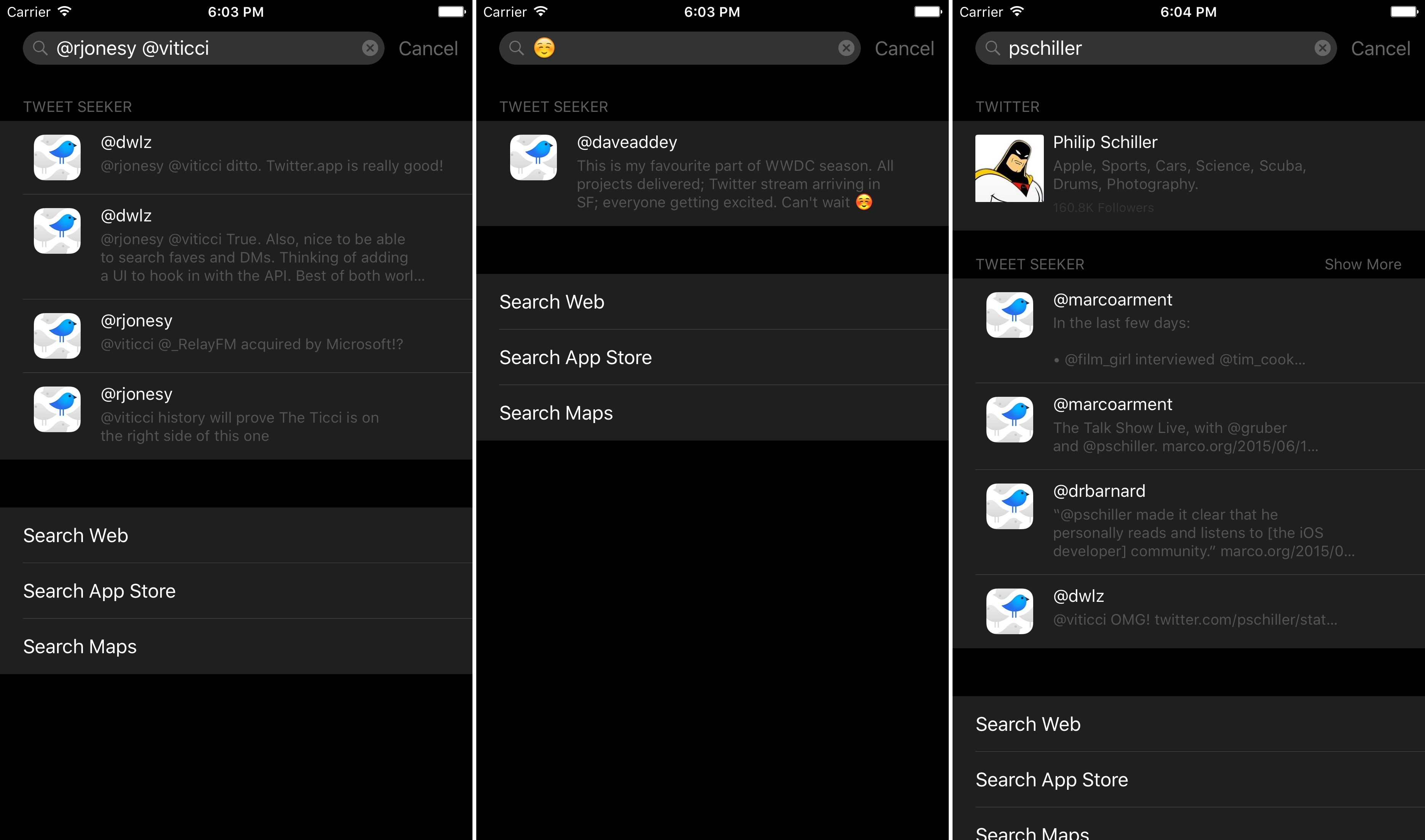

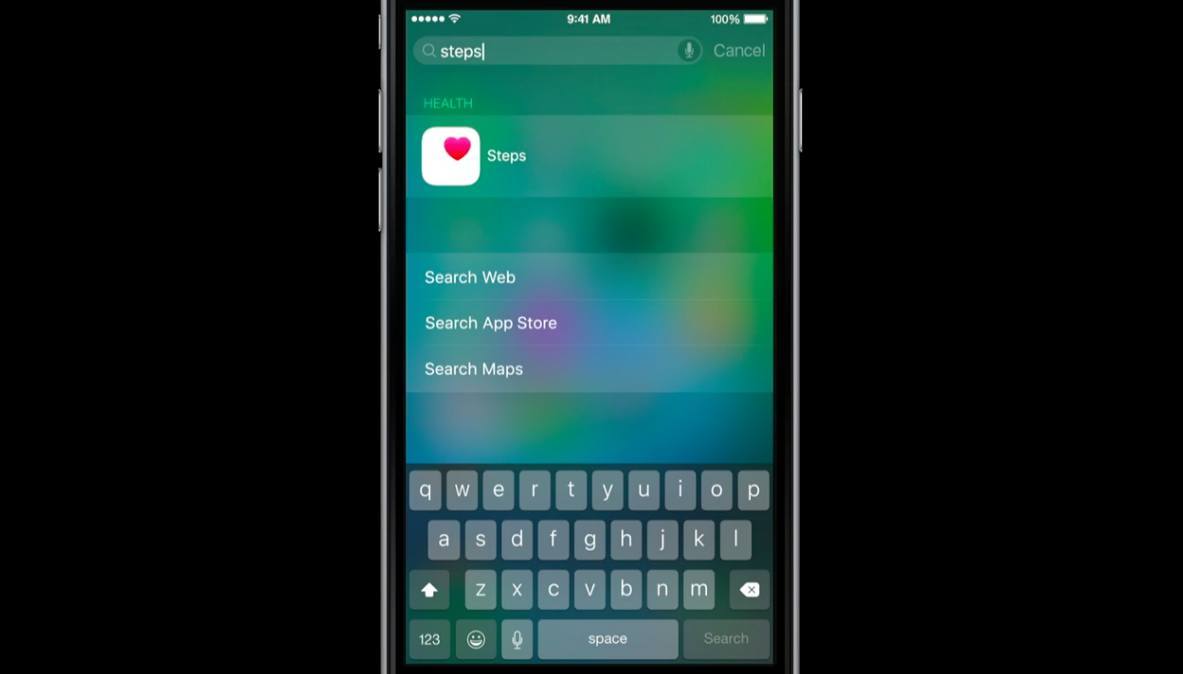

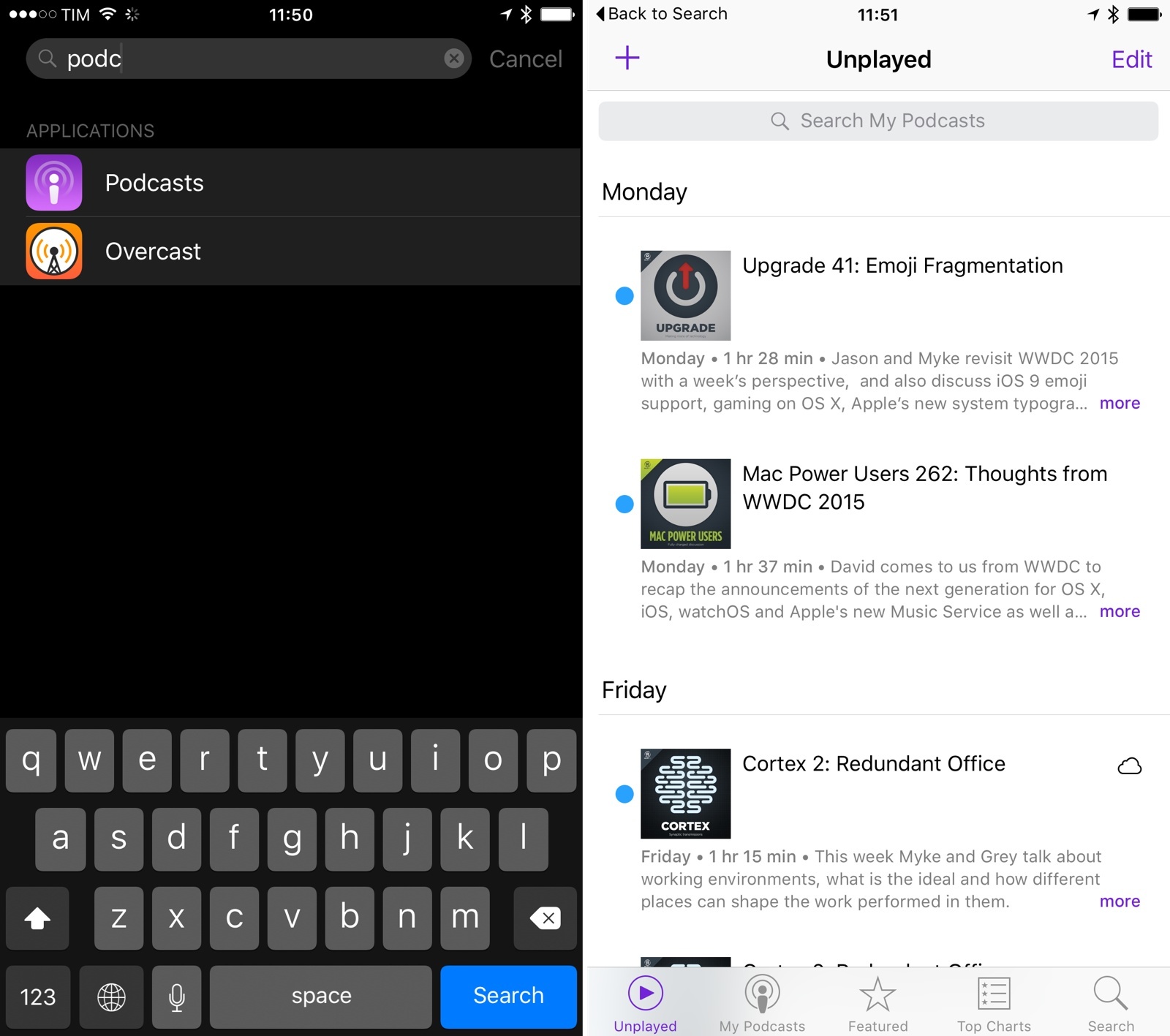

Apple’s search initiative for iOS 9 replaces the existing Spotlight feature on the iPhone and iPad and extends its capabilities beyond launching apps and searching for data from partners such as Bing and Wikipedia. With iOS 9, users will be able to look for content stored inside apps, such as documents from iCloud Drive, events from a calendar app, or even specific features of apps such as steps from a pedometer or direct messages from a Twitter client. Search will be based on the same design of iOS 8’s Spotlight – tap in the search bar to start searching. Results will open inside apps in the relevant section, and users will have a way to easily return to search results with a back button.

For users, Apple’s goal is to keep app search as streamlined and obvious as possible. For developers, the adoption of search encompasses multiple aspects of app and web design. While it’s not hard to imagine that most developers will want to start offering content from their apps as search results, some of them will have to carefully consider the benefit of exposing information to users.

In iOS 9, developers will be able to index content from their apps in two ways. The first technology – and likely the one that will be the most popular across iOS apps – is local app search based on the CoreSpotlight framework.

Local App Search

With local app search, iOS 9 can build an index of content, app features, and activities that users may want to get back to with a search query. Built like a database and already in use by Apple apps such as Mail and Reminders, CoreSpotlight will provide low level access to the index of an iOS device, making it easy to organize and retrieve content users have previously seen, created, or curated.

Developers will have complete control over what can be indexed, how results appear in search, and what happens when a user taps on a search result. Apps will be able to refresh the content available for indexing in the background by managing entries in the database. If, for instance, a todo app supports local search but its item list changes often through remote sync, it’ll have a way to update the list of todos available to search without being launched. The process wants to be lightweight and invisible to users.

It’s important to note that Apple isn’t building a traditional document-based search feature for iOS. For the past two years, the company has been enhancing its Spotlight search tool with external integrations such as Wikipedia results, movie showtimes, and snippets of web results from Bing, but iOS 9 wants to further expand search to account for the richness of data inside apps. While users will be able to launch apps and look for documents – two common use cases in the OS X Spotlight – the company’s focus is to reimagine search for the unique nature of apps.

For the first time on iOS, third-party developers will be able to make their app content searchable, and many of them are excited about the possibilities opened up by the new APIs in iOS 9. “Local app search seems like a must for some of my apps”, Greg Pierce, developer of productivity apps like Drafts and Terminology, told me this week. “There is a lot to like about Apple’s new Search APIs”, Pierce added, noting that it’s important to give developers control over what can be indexed locally on iOS, removing the potential pitfalls of ending up with cluttered search results that aren’t useful.

Mike Singleton, VP of Engineering at Foursquare, told me that “Foursquare is perfectly suited for native search, making it easier for people to quickly find places or suggestions they’re looking for”. Foursquare removed the requirement to create an account to use the service, and the company could implement app search to let users look for places or even browse entire categories of places nearby. A search for “burgers” on iOS 9 could open search results for burger restaurants nearby directly in the Foursquare app, he said.

Loreto Parisi, head of app development at popular music lyrics service Musixmatch, also told me they “are going to support the new CoreSpotlight API in order to index locally app contents like lyrics, artists, and album pages”. On iOS, Musixmatch is able to match songs from a user’s Music app and present real-time song lyrics in an alternative music player. In theory, Musixmatch could let users look for bits of lyrics they remember and allow them to jump straight to the full lyrics in the app. Not even Apple’s Music app supports this type of search at the moment.

The way Apple has designed local app search is reminiscent of viewing history in web browsers: users want to be able to find things they’ve seen in the past; from this standpoint, local app search will be more akin to a local app history, enabling users to find apps, but also files, pages, profiles, likes, comments, and other types of previously seen content.

Part of this technology falls under the umbrella of user activities, appropriately based on the NSUserActivity API launched by Apple last year with Handoff. Search and Handoff share the same foundation: just like an app can let users resume their activity on another device by handing it off wirelessly, local search will index those activities1 and make them available to users outside apps. This more abstract – and volatile – idea of search is based on the principle that modern apps aren’t static containers of files. They’re experiences, and iOS 9 can index the activity that takes place inside them.

Joe Fabisevich is the founder of Picks, a todo list for books, songs, movies, and other items that users want to collect and share. Adopting app history is “a no-brainer” for Picks, he said. “Instead of a multi-step process of having to open the app, find the list you put an item on, and tapping it to reveal more information, you can just type a few letters and have it pop up in Spotlight”. As Ortwin Gentz, developer of Where To? told me, “the unified search feature brings iOS one step closer to the Mac”.

According to developers who have already started working on supporting search for iOS, the technology is easy to implement. Brian Donohue, lead developer at Instapaper, told me that he went “from nothing to a working implementation in an hour during WWDC”.

Dan Loewenherz was also happy with the initial results from adopting app search in the iOS 9 developer beta. Loewenherz makes Pushpin and Tweet Seeker, two search-oriented apps to manage bookmarks on Pinboard and search for tweets, respectively. Implementing local app search was “incredibly easy” for him, and it took “less than three hours from opening up the documentation to having a perfectly running build” on a test device.

A simple API will be critical to widespread adoption, but it can also have unexpected consequences on the nature or business model of an app.

Instapaper, for instance, has long offered a full-text search feature to premium subscribers. This poses a dilemma for supporting search on iOS 9. “If we’re going to launch Spotlight search”, Donohue told me, “we need to fundamentally rethink Instapaper’s search product which is currently only for Premium users”. For other apps that offer search as a paid option – a common choice in RSS readers or advanced text editors – the next few weeks are going to be interesting as their developers figure out how to balance search as a paid option and search as an iOS feature.

Developers aren’t the only ones affected by local search, however. At this point, it’s not clear if users will be able to choose which apps are capable of displaying results in the search page.

For a long time, users could disable Spotlight sources they weren’t interested in, but the first beta of iOS 9 doesn’t have settings to deactivate third-party apps. Without proper controls to decide which results from installed apps can appear, iOS 9’s search page could quickly fill up with choices, giving users too many options simply by installing apps that implement indexing.

Beyond questions and concerns, though, it’s undeniable that local app search has the potential to deeply change how users find information in the apps they use every day. Apple’s decision to put developers in control of what is indexed can pay off in versatility and usefulness. When an app isn’t limited to files but can index any local data and activity, it makes it easier for users to return to content they remember and value.

And yet, Apple has bigger plans than local app search as they want to index an even larger source: the web.

Apple’s Cloud Index

Unsurprisingly, Apple isn’t taking a traditional approach to indexing the web.

When evidence first surfaced that the company had started using their own web crawler (later outed as Applebot) to index webpages, speculation quickly raised suggesting that Apple wanted to take on Google with a new web search engine. Apple later clarified that Applebot was designed to power Siri and Spotlight Suggestions on iOS 8, and with iOS 9 it’s clear that Applebot will play an integral role in supporting Apple’s search initiative.

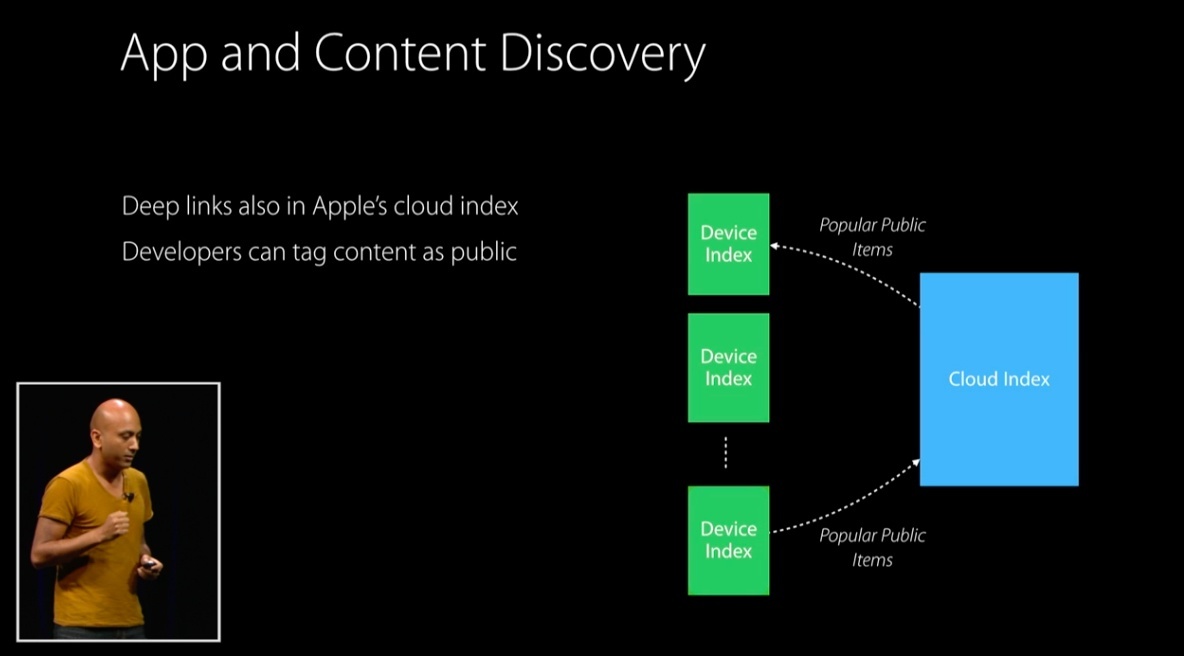

Apple is building a cloud index of user activities and web content. As the company describes it, the cloud index will “inform any searches by any user of your app on any device”, and it’s broadly aimed at creating a public and anonymous index of what users look for and engage with. Part web crawling and part a crowdsourced search database, Apple’s cloud index will be closely tied to apps and results from it will be displayed in the search page of iOS 9.

The company offered a few examples of how local app search and results from the cloud index could work in tandem on a user’s device. In a technical session, Apple engineers showed how Airbnb had started working with the search APIs to index their reservation data and app content. With iOS 9, Airbnb users will have the ability to look up reservations from the app in search, where they’ll be shown as rich snippets with previews and buttons to call or text a host without ever opening the Airbnb app.2

Let’s assume that Airbnb, besides local app search, wants to let users discover new content they haven’t previously seen in the app. This is where the cloud index comes into play, and where Apple’s plans are more diversified.

Developers have choice when it comes to the cloud index. In an iOS app, they can tag user activities as public, and public activities get sent to Apple’s cloud index as anonymous hashes. These are the activities that iOS uses to index local app content. In Airbnb’s case, they could be apartments a user views or lists of search queries.

Because Apple doesn’t want sensitive data and personal activities to be sent to the cloud index as they wouldn’t be useful to others, user activities are private by default and developers are strongly advised to tag an activity as public only when it could benefit other users. For example, a user’s step count would be useless as a public activity, but an Airbnb listing viewed by millions of users in the Airbnb app for iOS could inform a reasonable assumption that such listing is popular. If Apple’s cloud index marks that item as popular, it’ll start showing up in search results on iOS 9 even if a user hasn’t previously seen it in the app.

Foursquare is a good example of how the cloud index may help apps make their content more discoverable. Singleton told me that they’re “certainly going to make use of public indexing”. “Since nearly all of our content is public we’ll also be marking most NSUserActivities as publicly indexable”, Singleton added, saying that they started supporting user activities last year with Handoff for iOS 8. Foursquare is still trying to understand how indexing all this content could work with iOS search, though. “We may index a large portion of popular venues in your city so those are easily accessible, but we’d like to better understand the implications of indexing a large amount of data before committing”, he concluded.

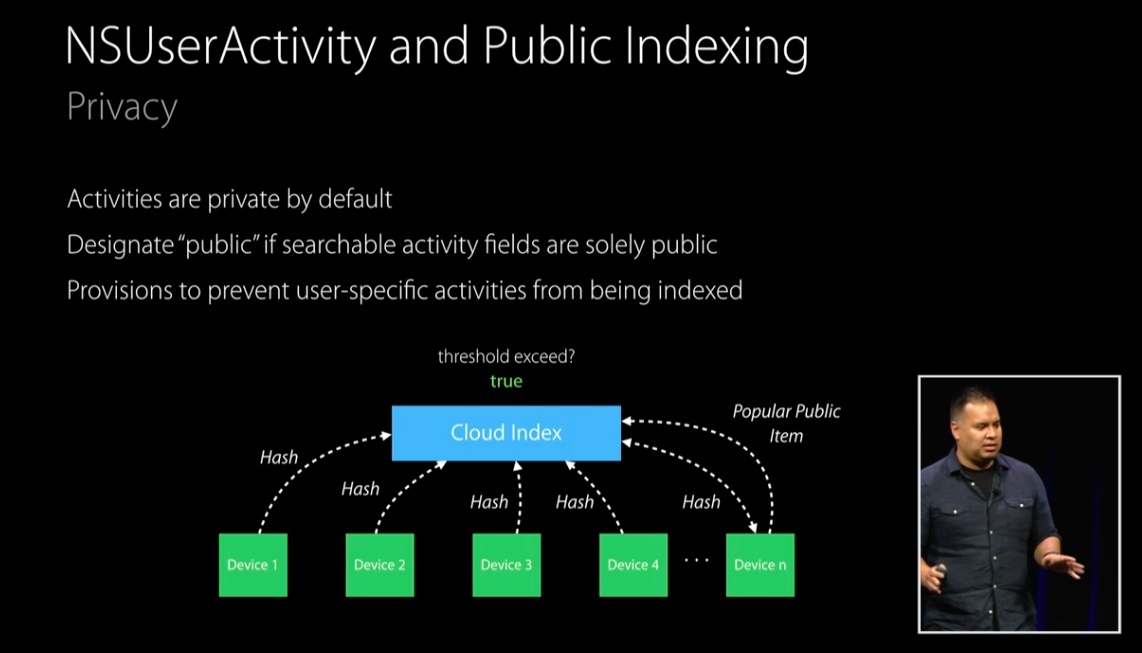

At this point, it’s fair to wonder how, exactly, Apple is planning to rank public activities in the cloud index and offer them as suggested results in search. To achieve this, the company is employing a second layer of filtering: Apple will track “engagements” with an activity and popularity in their cloud index to determine whether a public result can be useful or not.

According to information detailed at WWDC, the cloud index will have a threshold for each public activity that is submitted as a hash. Until a popularity threshold is met, activities don’t stay in the index and they’re immediately discarded. When an activity meets the threshold, it becomes a popular public item, which allows Apple to recommend it as a suggested result for some queries. Then, Apple continues to keep track of engagements in search such as views and taps, continuously refining results that are suggested to users.3

Essentially, Apple has recognized that iOS apps can be treasure troves of public information, and they want to understand what users look for. To do this, they’re using the concept of a user activity as a data point, which may or may not result in a cloud-indexed item that eventually propagates to other users with the new search page.

Activities won’t be the only data point that Apple will use to feed the cloud index, and this is where Applebot starts to make sense as part of a bigger plan.

For the past several months, Apple has been crawling websites they deemed important to index their content. But in building search for iOS, they realized that apps often have associated websites where content is mirrored or shared.

Apple has been quite ingenious here. To understand the relationship between website and app, they’ve started from an unexpected but obvious place: iTunes Connect. When they submit an app to the App Store, developers can provide URLs for marketing and support websites of an app, and Apple can match those websites against the app and crawl them for possible cloud index candidates that could power search. In Fabisevich’s case, Applebot could find Picks on the App Store, see its associated website, crawl it, find content offered for indexing on the web, deduplicate data indexed by the app and website, and evaluate its presence in search results. If Picks users subscribe to the same public list, iOS 9 should – in theory – be aware of it thanks to Applebot and the cloud index.

Web Markup

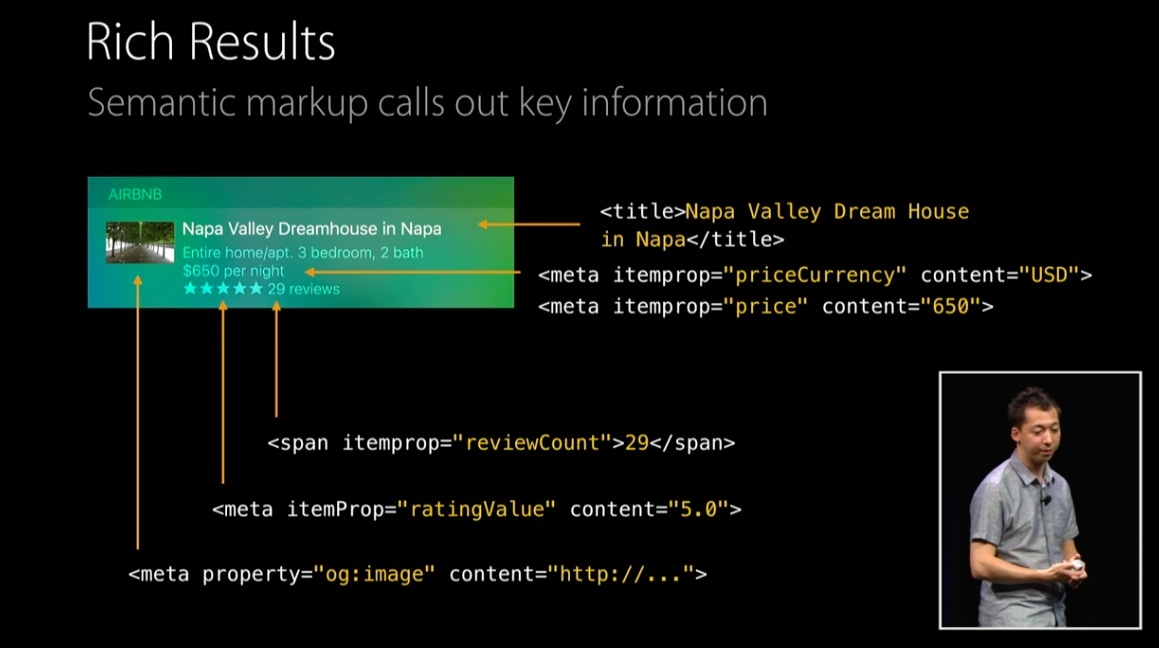

To enhance web crawling with structured data and, again, give developers control of indexed content, Apple has announced support for various types of web markup. Developers who own websites with content related to an app will be able to use Smart App Banners to describe deep links to an app (more on this in a bit) as well as open standards such as schema.org and Open Graph.

Apple calls these “rich results”: by reading metadata based on existing standards, Apple’s web crawler can have a better understanding of key information called out on a webpage and do more than simply parsing a title and a link. With support for schema.org, for instance, Applebot will be able to recognize tagged prices, ratings, and currencies for individual listings on Airbnb, while the Open Graph image tag could be used as the image thumbnail in iOS search results. An app like Songkick could implement structured data to tag concert dates and prices in their related website, and popular concerts could show up for users with rich descriptions in the iOS 9 search page.

According to Foursquare’s Singleton, the company has already done most of the work required by Applebot. “Our website has been using Open Graph, Twitter Cards, and schema.org metadata for years, so we’ve done most of the work to make our pages friendly to the Applebot crawler”, Singleton said.

It was somewhat surprising to hear Apple talk about the benefits of structured data on the web based on open standards, but it’s the right strategy to ensure Applebot can see the web as modern web services can. When you see descriptions and previews for links shared on Twitter, Facebook, or Slack, Open Graph is usually behind that rich presentation. Apple wants the same to be true for iOS search results.

The advantage of native search as opposed to a web search is, unsurprising, native access to device and OS features. At launch, Apple will provide three actions for rich results: dialing a phone number, getting directions to a place, and playing audio or video. These actions will appear as buttons next to a search result and they won’t require users to launch an app to execute them. Audio for a podcast episode will start playing directly from search, and Maps will automatically open with directions after the button is tapped.

It’s interesting to imagine how, in the future, the actionable interface of rich results could be adopted for an even wider range of actions, such as paying for items (a buy button for search results) or letting developers define their own custom buttons.

App Discovery

As Apple noted during its Search session at WWDC and in developer documentation, iOS 9 search will also be used to help app discovery for both developers and users.

Discovery of apps that contain content relevant to a search query can take place in two ways. If a website indexed by Apple is displayed as a search result, that website will be able to use Smart App Banners to inform users about an associated app. The technology isn’t new to iOS, but as web results get plugged into search more often, users will likely come across Smart App Banners more regularly, which, for developers, could help with converting a website user to an app user.

Thanks to cloud indexing, users could also receive results for apps they haven’t installed on their device. Tapping a result for an app that isn’t installed will bring up an App Store sheet to download the app and “continue exploration” inside it, although Apple didn’t offer any demo or additional details of this flow.

As Apple writes:

In addition to improving the user experience, adopting Search helps you increase the usage of your app and improve its discoverability by displaying your content when users search across the system and on the web. For an example of how this works, imagine that your app helps users handle minor medical conditions, such as a sunburn or a sprained ankle. When you adopt iOS 9 Search, users searching their devices for “sprained ankle” can get results for your app even when they don’t have your app installed. When users tap on a result for your app, they get the opportunity to download your app. Similarly, users can get results for your app and related web content when they search for “sprained ankle” in Safari. Tapping on a result in Safari takes users to your website, where they can download your app from your App Banner.

For developers, the ability to show up as data sources that can turn into app installs could be a new avenue to let users discover their apps. With over 1.5 million apps, traditional search and curation on the App Store can only cover a portion of the apps users may need. Leveraging search as a discovery mechanism could bring more variety and personalization to the apps that are suggested to users. This, of course, provided that Apple’s system will scale, deliver fresh results, and be accurate. Developers shouldn’t count on search as the ultimate discovery engine for their apps, but it has the potential to be a welcome addition.

Apple isn’t first to using search as an app discovery tool. Back in April, Google announced the ability to discover content from apps that aren’t installed on an Android device through App Indexing. It’s too early to tell whether search results as an aid to app discovery could deliver meaningful returns to developers in the long run. But for apps that offer public indexable content, this could be a new level of exposure to users.

Deep Linking and Universal Links

Deep linking is where every piece of Apple’s puzzle comes together in a cohesive experience. iOS 9 marks Apple’s long awaited foray into native deep linking, and the company is betting heavily on deep links as a superior way to launch apps, navigate them, index content, and share results.

Deep linking refers to the ability to link to a specific section of an app. Deep links are URLs that open apps into discrete navigation points and pages, such as the Steps screen in the Health app, a profile view in Tweetbot, or an email message in Mail. With proper support from developers, any app screen or activity could have its own deep link, which allows users to get back to it at any time.

Deep links also provide structure. By analyzing the deep links supported by an app, Apple can understand which sections it needs to index. Smart App Banners will allow the company to match webpages and app pages, linking users directly to the relevant area of an app after they tap a result that was first indexed on the web. Under the hood, deep links want to lay a new foundation for launching and navigating apps on iOS.

Every search result on iOS 9 will use a deep link to take users into the content they’re looking for. If you find a recipe with search, tapping it will take you to the recipe screen in the app. Found a song? The associated music app will open showing that song. Same for email messages, listings, books, bookmarks – any item, view, or sub-section of an app you can think of.

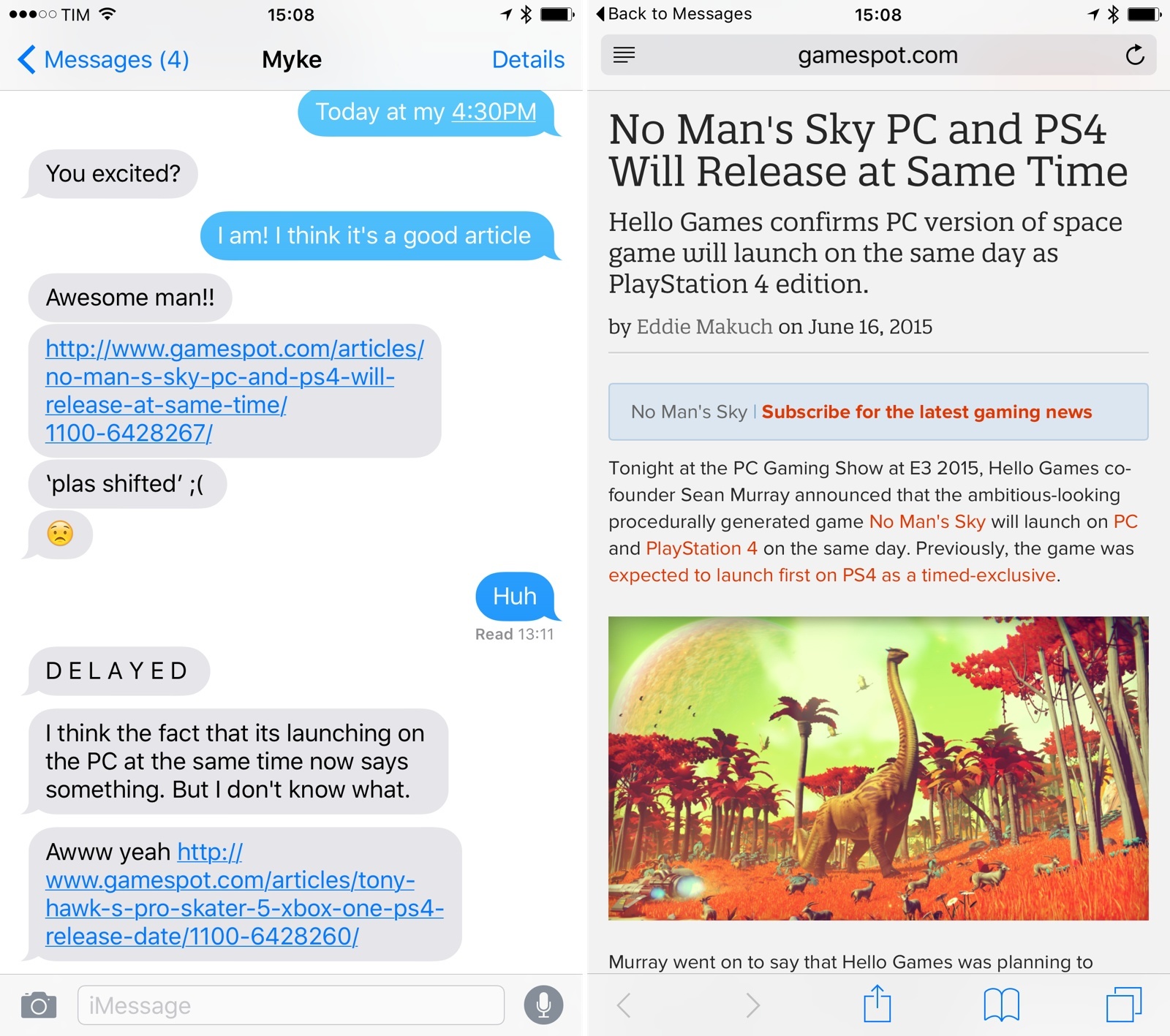

iOS 9 will make it easy to switch back and forth between search and apps with deep links and back links. The latter is, effectively, a back button that all apps get “for free” (they don’t have to do anything special to support it) in the top left corner.

The button will let users go back to the previous app – in the case of app search, it’ll let them flip through various results with the convenience of hitting a button to return to the list of results. Back links that open deep links (it’s quite a mouthful) will work for both native apps and Safari, for web results and app results – they work all the time on iOS 9 even if you open a link from Messages or Twitter. Currently, the animation used to launch apps and return to them feels less like launching and more like navigating pages of apps across iOS.

“We’re really excited about the new UI Apple has made with a native back button, and quick slide-over animation that should make these transitions feel really lightweight”, said Singleton. In Foursquare’s case, the company’s decision to offer two complementary apps – Foursquare and Swarm – should result in a better experience thanks to the back button – switching between them as needed for check-in and browsing places will be faster and more intuitive.

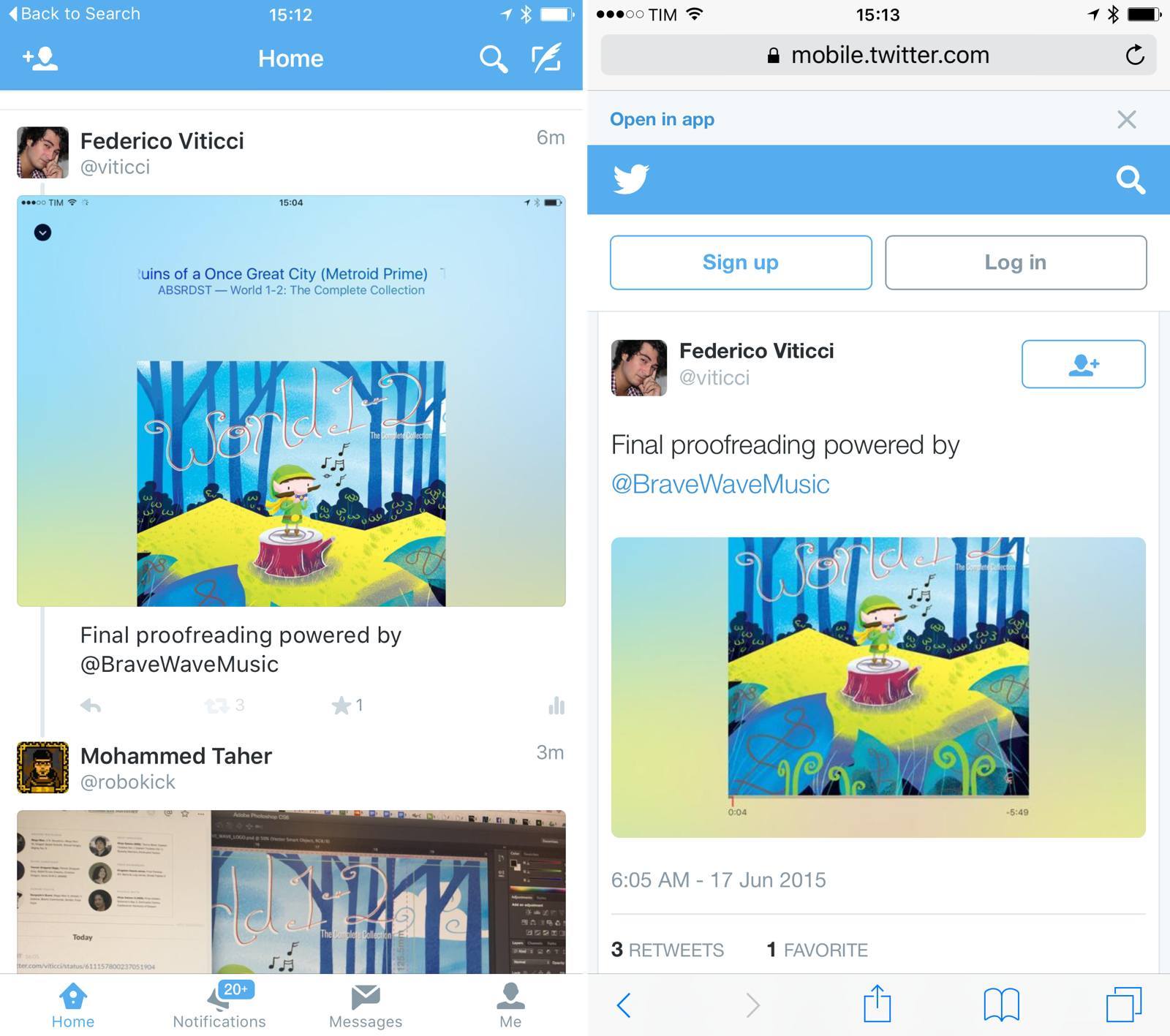

Apple’s plans for deep linking, though, extend beyond native integration in search results. At WWDC, Apple also introduced Universal Links, a way to launch apps as easily as websites with traditional HTTP links. With Universal Links, Apple wants to let websites and apps communicate through the common thread of a URL, with verifiable ownership, graceful fallbacks, and cross-platform support.

To understand how Universal Links will work, imagine that Twitter will start supporting them for twitter.com and their iOS app. Every time you tap a link to a tweet on iOS 9, that link will automatically open the tweet in the native app instead of Safari if you have it installed. If you don’t have the app or share the link with someone who doesn’t have the app, the link will open in the browser as usual because it’s a normal URL.

Universal Links carry some important benefits over the old way to link to specific areas or features of apps, custom URL schemes. Universal Links are always mapped to the right app: while different apps can claim the same URL scheme on iOS, Universal Links work by matching an app with a signed certificate on the website, and this will ensure that links from a certain domain will only open in its native app. Universal Links always work because they are platform neutral: if the app isn’t installed, they go straight to the web. With custom URL schemes, if you don’t have the app installed and tap the URL, it does nothing.

It was obvious for Apple to elect web URLs as the best way to link to apps: web links are omnipresent in today’s communications, they work everywhere, and they allow for server-side metadata. Developers will have to manually add support for Universal Links in their websites and apps; for users, regular links will simply start redirecting to sections of native apps.

After talking to developers for the past week, it appears that Universal Links will deeply affect how apps offer to share their content, with interesting implications to consider.

“I think Universal Links are going to be a game changer”, Fabisevich told me, adding that “getting to an app was a very bad user experience, always ending up with an empty tab in Safari, and having to wait for the web to load the content to tell you to be redirected to the app”. He refers to apps that implemented deep links before iOS by automatically redirecting Safari to native apps, a less than optimal solution.

Foursquare is also excited about the possibility of giving users an easy way to experience Foursquare inside the app. Singleton said that they’ve been “hoping Apple would build something like this for a while”, as they believe “anyone who’s finding their way to foursquare.com should be using the app when possible”.

“Developers have been doing deep links for a while now, and they’re great, but it stinks not being able to send someone a web link, and having it go into an app directly”, Fabisevich said, and his comments ring especially true after Apple’s announcements.

At WWDC, Apple said that Applebot will be able to uncover deep links by parsing metadata from Twitter Cards and Facebook App Links, two existing deep linking solutions from the social networking companies. “Their crawler, Applebot, already incorporates other popular graph tags such as Twitter, something Facebook would naturally resist, and that gives Apple more data that they can use in their search”, Fabisevich added.

This is one of Apple’s biggest advantages: by nature of being the platform owner, they don’t have any direct interest in Twitter or Facebook, therefore more data is better data. Apple can crawl Twitter and Facebook deep links to build a better index, and they also confirmed they will add support for more popular deep linking standards in the future. And on top of that, they can build a superior user experience that automatically associates links with apps and that offers a native back link in the status bar.

“Universal Links make the entire Internet a part of the app experience”, Loewenherz told me. He noted that accounting for navigation to websites on a mobile device tends to be one of the most common concerns for app developers, but that “has been eliminated” with Universal Links. “When you think about it, Apple has figured out a way how to make the entire Internet a part of its native platform”, he said. That may be an overstatement in some ways, but there’s no denying that Universal Links make any URL eligible for native app integration. “Universal Links give apps the ability to deep link into other apps, provide a built-in fallback to Safari, and protect user privacy all simultaneously. Big wins there for most stakeholders”, Donohue commented.

“This summer I planned to create a web presence for the data in my app”, said Daniel Breslan, a young indie developer from the UK. Breslan makes Departure Board, an app to check local train information and departure times.

After WWDC, he’s sure he wants to build a web counterpart for his app. “With the simplicity and ease of integrating Universal Links into my app, I will definitely build it”, Breslan told me, and his primary motivation is a common point among developers I spoke with – sharing. “Universal Links will greatly improve my app as sharing a train will no longer just be a textual description, but it will load a fully interactive, live, native view of the train information”, Breslan noted.

Questions and Concerns

For all the excitement and promising features, there are some doubts and questions about Apple’s search and deep linking efforts that don’t have an answer today.

For local app search, it’s not clear if Apple will let users configure the apps that can display results in the search page. As I mentioned above, a lack of controls could become problematic as more and more apps start making their content available to search. I believe that Apple should provide users with an interface to turn off third-party apps for search, as the current solution isn’t flexible or obvious enough.

What’s also difficult to consider today is how Apple’s cloud index will scale and how iOS 9 will balance local results with cloud results from websites or apps that aren’t installed. How aggressive will iOS 9 be in recommending content indexed publicly by Apple? How beneficial will the cloud index be to developers of niche apps that can’t meet high engagement thresholds? As millions of apps and websites start tagging their content as public for Applebot, will a simple search page be enough to always cull the best content and let users navigate to it quickly? Will search be fast?

On the surface, Apple is serving their own interests by deeply connecting web results and links to native apps that have to be downloaded from the App Store. This gives Apple the opportunity to redirect users to native apps more frequently and consistently. In return, users get an easy way to search for information, launch apps, and share content with others.

At a deeper level, the cloud index is the epitome of something that’s always been true at Apple: native apps offer superior experiences, but the web is not an enemy. With Applebot and the cloud index, Apple is using the web and their own users to demote the middlemen – search engines like Google and Bing – for results that can be linked natively to an app. And that’s where the question about balance comes in: with different search features pulling in different directions – local search, cloud index, app discovery, deep links – can Apple build a search product that’s easy to use but advanced enough?

How Apple ranks results will play an essential role in the debut of app search. At WWDC, the company explained that they’ll use three metrics to evaluate results in the cloud index: URL popularity, frequency of views for activities, and user engagement. Apple didn’t provide more details on the algorithms behind these broad levels of analysis, and we don’t know yet if Apple will employ additional data points to present the best results at any given time.

The company’s inclination to collect as little data as possible may play to their disadvantage here: by not comparing data between different Apple services and prioritizing privacy over massive data collection, the risk is that web results in iOS 9 search may be generic and not contextual enough. Apple wants to build a search feature that is ad-free and values privacy, but ads and extensive data collection were key to Google’s success in offering a robust search engine at scale. Apple promises to constantly downrank results that are poorly formatted or not relevant, but as Gentz put it, it’s easy to “see the SEO cheater cat and mice game we all went through on the web” becoming an issue with the cloud index.

There’s a point to be made about users knowing about the power of search on iOS, too. “If Apple markets Spotlight features as well as they have apps, it might become a new interaction mechanism”, Fabisevich noted, “but if users don’t know of its capabilities (like with extensions) they might not even realize all the great (and semi-complex) power available”.

When Apple introduced extensions last year, they lauded their power and simplicity: extensions are bundled with apps, and they offer actions that can let multiple apps communicate at once. And yet, most users don’t know about action and share extensions, how they can be configured, and what they do. For better or worse, iOS users are accustomed to the concept of searching the web for information and it may be tricky to tell them that a whole new layer of information can be experienced in the search page.

On other hand, Apple making results available from suggestions in Safari may cater to those problems and use cases. Over the past year, I’ve enjoyed the ability to quickly get to Wikipedia pages from rich results in Safari, and if the same system can be extended to apps – whether they’re installed or not – and be relevant, that could be a big win for Apple and developers.

Universal Links have also been met with a fair share of skepticism from developers I spoke with. On paper, Universal Links are great: with a normal URL, iOS can open native apps in the appropriate section. However, this could be an issue for smaller developers that can’t claim popular domains, as well as cause confusion.

“The pitch for Universal Links at WWDC came across as something focused on delivering what the big media/content companies want”, Pierce noted. “Apple already does this sort of thing for a few special domains, like YouTube, opening the web links in the app if it is installed and it creates a level of unpredictability to clicking on a link that may disorient users”.

Pierce has a point: if Twitter links start redirecting to the Twitter app automatically, users may miss the benefits of having tweets open in Safari. For example, Twitter doesn’t use share sheets, while Safari has them. A company’s interests aren’t always aligned with those of Apple and iOS users. Safari treats all web content equally with the same share and navigation features, but a link that skips Safari and opens in the app may, in some cases, lead to an inferior experience. “In a perfect world of well behaved apps, Universal Links sound like a good idea”, Pierce added, and his concerns are understandable in the early stages of iOS 9.

Universal Links also raise some intriguing app discovery questions. What happens when a user taps on a link that has a registered app available for download on the App Store? Will iOS 9 show a prompt to download the associated app? Loewenherz has been wondering as well, and he notes that “a toggle in Settings would probably be necessary to make it a little more user-friendly” if Apple indeed plans to leverage Universal Links to surface apps that aren’t installed.

Apple’s Bet on Apps

Apple has big plans for search, and they go far beyond local Spotlight results. Apple is building a new layer between apps and the web.

For users, iOS 9 search will be a simple search box with nice previews. Behind the scenes, Apple is leveraging Applebot, web markup, deep links, and user activities to fundamentally rethink the relationship between users, webpages, and native apps. In all this, the underlying theme is to find content from apps whether they’re installed or not and to get to results quickly. If Apple’s plan works – if it becomes far more convenient for users to find what they’re looking for and for developers to make their apps discoverable and indexable – iOS 9 search could be a serious threat to Google’s search business on iOS.

After talking to developers and studying Apple’s announcements at WWDC, it’s clear that Apple is tackling many variables of the search equation at once. They want to reduce the time spent navigating apps by exposing their features and data to search. They’re building a consistent way to open apps and results with deep linking and Universal Links. They’re planning to index web content and match results with apps to blend the two in a cohesive sea of information – a way to “expand an app’s presence beyond just users who have opened an app”, as Singleton put it.

There are many moving pieces and some details are scarce at this point, but it’s abundantly obvious that Apple isn’t taking a half-baked approach here. iOS 9 search goes deep into native apps and the web, with simplicity and privacy at its core.

iOS 9 search represents an evolution of the app structure, aided by the web. Apple’s goal is to create a search experience that uses the web to complement native apps, not to challenge them. As a result, more developers will consider building open web counterparts for their apps to provide structured information that would be hidden otherwise.

The integration that Apple is envisioning is the kind of access that Google will never have on iOS, and that has the potential to drastically change what iPhone and iPad users expect from search. Rather than indexing every possible piece of local or public content, they’re giving developers choice and they’re building a ranking system to only offer popular and relevant results. If Apple can pull this off, I bet that, for many, there won’t be a need to open Google.com because the best results are only a swipe away. And they seamlessly go to apps every time.

Four months from now, imagine that Twitter, Evernote, Spotify, and Foursquare will support search and Universal Links on iOS 9. You’ll be able to search for songs and notes – whether you’ve already seen them or not – and get results directly from the new search page on iOS. Or, you can keep discovering new stuff as you normally do, by texting with friends, checking Facebook, and following interesting people on Twitter. Found a link to a Spotify song? Tap it, you’ll skip Safari and web views altogether, and you’ll open the song in the Spotify app. A friend recommending a new restaurant with a Foursquare link on WhatsApp, because she uses Android and doesn’t have iMessage? That link will open the place page in the Foursquare app for iOS 9, just by tapping it. Need to find that document you were working on or that Airbnb apartment you were considering? They can also be found with iOS 9 search.

Imagine this, for every app on your device, for every website associated with that app, for everything you’ve seen or done on iOS, from the convenience of a search box on the Home screen. This is the future of seamless communication that Apple is envisioning with search, deep links, and Universal Links. Google isn’t involved in any of this – developers are. A new search experience, powered by apps and the web.

As Fabisevich noted, “Apple is enabling us to start thinking about apps outside of the icon”. In many ways, app search gives us a glimpse of what’s next for iOS.

- Optionally, with an expiration date so they’ll always stay fresh and relevant. ↩︎

- The concept of a push interface that brings actions to users isn’t new: Apple already started exploring this field with actionable notifications last year. Search, however, will allow users to be in control of the push interface, letting them find content and act on it directly from results. ↩︎

- Developers will also be able to proactively index interesting content that users may find useful, although Apple didn’t share additional details about this aspect. ↩︎