I have a confession to make: I’m a nerd. Yes, and I’m proud of it, because I think being a nerd means two things: I’m constantly curious about details, and I don’t hesitate to try out new stuff. To satisfy my curiosity, I’ve always dived into Apple’s ecosystem and the latest hardware related to it. Fortunately, my passion for Apple correlates with my love for discovering new music. I’ve been playing guitar since I was eight years old, and I love electronic music from the bottom of my heart as well. I’ve always found myself interested in both the traditional (perhaps organic) hardware side of music, and the more modern, digital software production process.

When the iPhone came out, many blogging colleagues and people around me predicted that its new software system, combined with the mobility of the device itself, would change the way people produce music and think about audible art as a whole. Three years later Apple unveiled the iPad. iPhone music software was indeed present at the time, but people soon recognized that the device’s screen was too small to create usable professional software for it — playing on-screen keyboards was nearly impossible and attempts to build high-end software synths like ReBirth or drum machines ended up in cluttered, untidy screens.

This problem seemed to get solved with the large screen of the iPad. Professional software retailers like KORG immediately started coding software versions of their most successful hardware. For instance, the iElectribe was one of the first apps available after the device’s launch. Over the years, I constantly tried out music apps for the iPad, tested hardware accessories (made possible with the release of iPhone OS 3), and never stopped investigating advantages, problems, and future possibilities of all those apps. Now, five years after the launch of iOS and the iPhone, I think it’s time to look back at how Apple’s mobile devices, with the focus clearly on the iPad, have changed the world of music and how they’ll continue to affect the future.

To do this, I recently went through my app archive and analyzed which kind of music apps remained installed on my devices, and which ones I liked when I tested them, but didn’t gain a place in my personal workflow. I discovered that I had to clearly divide music apps in several areas when discussing them. I distinguished between eight types of available music apps: promotion, discovery, entry level playing apps, handy/learning tools, sketching apps, recording, and professional software.

Throughout this post, I will cover each of those areas separately and point out their current state by discussing the most elaborate app(s) in their respective areas. I will point out the advantages and problems iOS brings to them, and predict — as far ahead as possible — what the future might hold.

Promotion

Let’s start with a very vibrant topic: promotion. The App Store’s low pricing policy (many apps are free or cost less than two dollars) is a great place to reach thousands of people for a new record or music project while still maintaining affordable PR costs. Many musicians — from big acts to rather unknown names — try to benefit from that. Let me take the audiovisual app experiment Ecclesia from electronic musician Forss and the interactive games from Linkin Park as two examples.

Forss is a relatively unknown musical project despite that Eric Wahlforss, the man behind it, created SoundCloud, one of the most popular online music sharing sites (I’ll come back to sharing later at the end of this story). Besides some interviews and the “classic” ways of online promotion — Twitter and Facebook — he decided to not just sell his new record as an album in the iTunes Store, but to separately develop an iPad app to realize his vision of a unique audio visualisation, tailor-made for his music. He started to sell his new record “Ecclesia” for $2.99 on the App Store. For this price, you get a 40-minute electronic music record, plus a journey through sound and a digitally processed landscape (if you’re interested in what the app looks like, read my review of Ecclesia).

Forss was able to combine his creative visions to increase the popularity of his music. He also set the price for his music by himself, since he did not sell it in the iTunes Store, which has price boundaries set by record labels. And by pricing Ecclesia very low compared to similar records (and by including visual extras), he might also have made some extra cash, since people are more likely to buy music when it’s inexpensive. If you can deliver great and innovative work, you can quickly gain more popularity when you promote your music through apps.

But what if your band already is popular, and actually does not need that kind of predatory-priced promotion? Say you are Linkin Park; what reason would you have for creating or allowing the publication of interactive games like 8-bit Rebellion or the new “let’s remix Burn It Down by driving a racing car” game, Linkin Park GP? Well, I think it’s not really about the cash, but rather about connecting with fans.

Linkin Park are one of the best examples of how bands can use social media to build and maintain a community among their fanbase. The band is constantly uploading Instagram pics of their latest shows, and they create exclusive giveaways for their Twitter followers (leveraging the power of social media). Many fans also downloaded the aforementioned apps, and share thousands of remixes and highscores every day. This has two prominent effects. Firstly, the band interacts closely with their fanbase — the fans get the feeling that Linkin Park actually care, and they don’t just see them as begging for money. Secondly, apps connect the fans to each other. Users can easily chat with LP enthusiasts all over the world through or because of these apps, and from there maybe add each other as friends on Facebook or even meet in real life. Music apps with integrated social media use music to support what platforms like Facebook were made for: connecting people all over the world to embrace friendship and to exchange opinions and cultural diversities (stemming from a common interest — in this case LP).

Discovery

Downloading apps from bands you already know is easy. What’s harder (especially if you’re a very highbrow music enthusiast) is finding new music that’s worth your time. On iOS, developers are still searching for the best methods to do so. There are some really good approaches available on the App Store, of which I consider Discovr (project founded by DJ and musician David McKinney) and Aweditorium the most elaborate ones.

Discovr Music is a service that uses algorithms to analyze its users’ listening behaviours, finding connections between artists. These connections are then showcased as an interactive mind map on your iPad. It’s a bit like Apple’s own Genius, but instead of just searching through your music library (displaying fitting results connected to your input) it includes all musicians users have listened to. It then proposes similar musicians and records to listen to. Discovr created this music discovery app as a direct competitor to the web-only project music-map.com. They also offer Discovr Apps (one of my tools to find cool, unknown apps to review on MacStories), Discovr Movies, and Discovr People.

What’s striking about Discovr Music is its handy UI, which makes browsing through unknown artists fast and simple. You can tap on images of musicians in a high frequency, view their biography and discography, and shortly listen to a demo track of interesting ones. This way of discovery is more fun and, what’s even more important, way faster than subscribing to blogs or YouTube channels, because most of the time, you’re just interested in finding new music and not the opinion of someone else before you even started listening.

While Discovr is an attempt to provide music the user is probably going to like, Aweditorium is based on a fixed artist database created by its developers. So it’s not about pinpointing what you might like, but more or less randomly showing interesting music. Although this might seem a bit useless for some people (to not have tailored music picked for you), it’s a really good approach to highlighting unknown artists on the main stage of the user’s attention. From a large “land map of artists”, presented using equally sized squares, the user needs to select an artist which is then zoomed to full-screen view, remaining the only visible element. This way, people cannot be distracted from other elements or other artists (unlike Discovr, where the app presents you with multiple artists at the same time). Users are forced to concentrate on one kind of music, and because of that are more likely to stay on an artist’s page to listen to the automatically-played demo track.

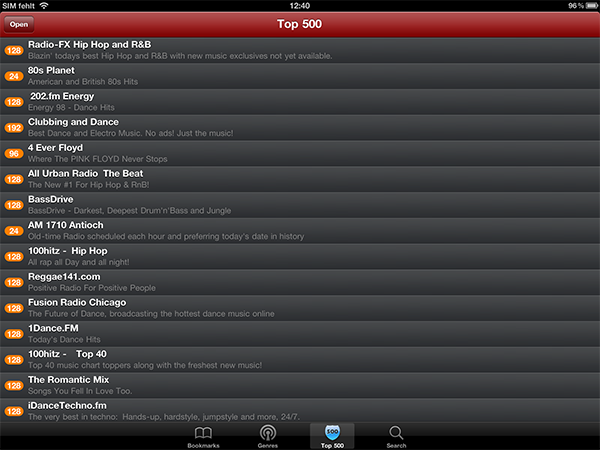

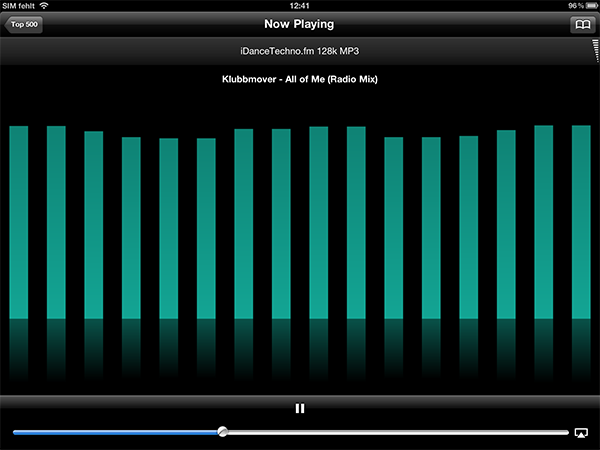

If you are a rather conservative music listener, or you like being surprised with new music like with Awedetorium, there is also a third solution to discover music on the iPad: Internet radio. New Internet radio stations are created every day, specialized on genres, music decades, subcultures, and so forth. If you spend some time searching the web, you’ll surely find one that suits your taste. All you need to do is download an Internet radio app, paste the stream link (or search through the apps’ pre-installed stations), and start listening.

My personal favorite radio app for both iPhone and iPad is Tuner by former Jailbreak activists Nullriver. It’s simple, fast, and for what’s most important for use over 3G: reliable. Tuner, like several other radio apps, also works in the background, so you can still use your iPad while streaming your favorite radio station through your headphones. If the radio station you’re listening to supports ID3-Tags, Tuner also displays the track info with artist and song title for further listening with paid streaming services like Spotify or Rdio. And when I’m at home, I can stream radio via AirPlay to my home stereo system and listen to all kinds of music in surround sound.

Differently from paid services like Spotify, most internet radio apps, and others like Aweditorium and Discovr, are either very cheap or completely free. This is the biggest advantage such iPad apps have to offer: they make it easy to browse extensive databases with hundreds and hundreds of artists easily — for free. When information about music and artists is free and easy to navigate through, there are more customers willing to buy music they discover.

Just playing some notes

When it comes to producing sounds with the iPad, though, the most basic music-making apps for the device aren’t truly comparable to desktop music software. Most of the free and $0.99 apps filed under the “Music” category of the App Store are so-called piano apps (I won’t give any specific example here, just type “piano” in the search panel in the App Store, and you’ll get hundreds of results). Most of the time they just feature an on-screen keyboard and maybe 10 to 15 different sounds. There are no recording options, no sharing features, nothing. These are the kind of apps people tend to download after setting up their first iPad and want to try out its magic. It’s the “Look, I’ve got a piano on my iPad, and I can make cool sounds with it” effect. But if you think about it, there is not that much magic in those apps. They are suited for occasional App Store customers, people who already believe that no app on the App Store should cost more than a dollar. But not everything that is free is worth a download.

Although many of these small apps are poor (they can be an affront to professional musicians), they also can be great for people who have always wanted to try out a musical instrument but fear to buy a real keyboard and learn the piano. Most of the time, people hesitate to buy an instrument because they think they won’t stay enthusiastic for a long time. Even the upfront cost of owning an instrument is too high. For such customers, a free piano app (or an on-screen guitar app) can help in making a better purchasing decision if they like the sound and playability of a certain instrument. And if you offer some learning information or even small melody tutorials within such small music apps, maybe the customers will start enjoying making music, move on to a more professional program, or even get their hands on real instruments to improve their skills.

Small tools

In the same price range ($0.99), you can find small music tools like tuners or metronomes. These apps are usually iPhone-only, since no one needs a 9.7” screen for a metronome. If you find a good one, maybe even with a cool UI (see the Steinway metronome or Beats by bjango — not Dr. Dre — as striking examples), they help you a lot on the road. They are small companions for musicians, from laymen to professionals, offering a limited but clear feature set (no one needs to reinvent the metronome, as it’s perfect already), so you just buy and use them. They’re nothing spectacular, but at least you’ll never have problems concerning their usability and usefulness. And they are always with you and always available to download — so you’ll never forget your tuner anymore.

Making Music

Next up are the more specialized tools for ambitious musicians, which aid in learning new songs and skills. Talking in dollars, we’re speaking of the $1.99 to $9.99 category here. Some prominent music apps that come in handy for learning and easily working with your instrument wherever you are, are Apple’s mobile version of GarageBand, the tablature displaying app TabToolkit by Agile Partners, and the iPhone mixing app FourTrack by Sonoma Wire Works. These apps are serious efforts to enhance learning speed and are perfect entries into digital music production, recording, and playing.

The most complete music software for the iPad is provided by Apple itself: GarageBand. It has got a place in every topic I’ll cover from now on to the end of the post. GarageBand is a learning, recording, production, and mixing environment at the same time. GarageBand for iPad offers all kinds of different ways of creating sounds one could imagine. Its on-screen instruments are working fine for more or less any music genre (save the normal drum set). The other smart instruments (drums, strings, guitar, and piano) and manually controlled instruments (piano and guitar) are all very handy and make GarageBand usable for both interested beginners and advanced musicians. For even more professional users, you can record MIDI keyboard input via a USB keyboard (like the portable and very cheap KORG nanoKey) connected to the USB Camera Connection Kit. To play specific harmonies, you can select all kinds of scales for easy melody playing with the software keyboard and guitars.

Speaking of guitars — how is it possible to record an electric guitar sound with GarageBand? Obviously, the iPad does not offer that many external input possibilities. There are only two: the headphone jack and the dock connector. Since iOS 3.0, the iOS SDK includes an API to code apps with connected hardware accessories. This made iOS a gold mine for software companies coding software emulators of musical instruments. As I already said, keyboards are easy to hook up to the iPad, and their electronics are already optimized for digital use with software. However, electric guitars are not (they are completely analog) — you need an interface or a microphone to record them digitally. Of course, there is a microphone in the iPad, but let’s be honest, it might be suited for voice dictation and Siri, but not for serious music recording. Guitar players needed better interfaces.

This market was soon covered by many products; early adopters for the iPhone were IK Multimedia with the iRig for their AmpliTube software, originally a VST plug-in for desktop apps like Ableton Live, and Peavey with their Ampkit Link. As both devices run the same OS, these accessories also immediately worked with the iPad when it came out. A newer approach, which is optimized for the mobile multi-track recording app StudioTrack on iPad, is the robust and way more flexible GuitarJack by Sonoma Wire Works. All of these small gadgets usually combine a 6.3mm to 3.5mm jack adapter (the GuitarJack also incorporates an 1/8 inch adapter for microphones), an audio interface, and a prolonged headphone jack to monitor guitar playing on your ears and practice silently. What’s really great about these adapters is that they are not just suited for the software of their manufacturers. I can use my AmpliTube iRig with GarageBand and this way take advantage of its great digital amplifiers (although the clean sounds are way better than the distorted ones).

Practicing

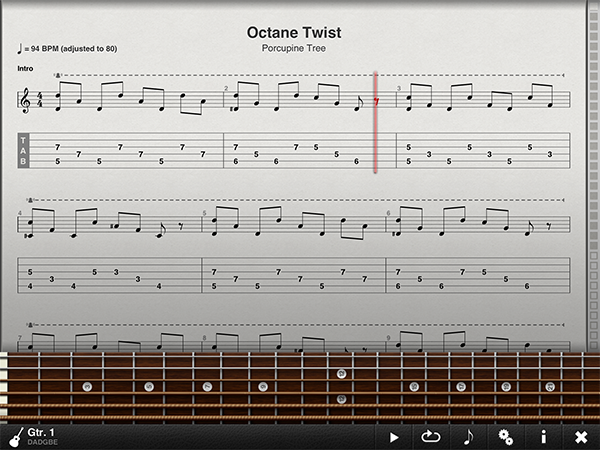

Now that you’ve got your guitar hooked up to your iPad and created an awesome sound, the next thing you probably want to do is practice. Whether you’re in a band, or just want to learn some of your favorite tunes, the easiest way to do so is using GuitarPro files. GuitarPro is the standard desktop software to create, edit, and play back guitar tablature. Often you’re in a place without your computer, but still need your tabs. What do you do? Use your iPad.

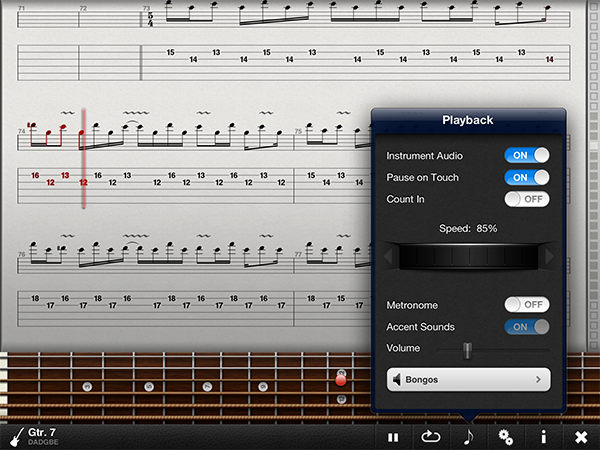

The best app in this field is definitely TabToolkit. Just copy already saved files from your computer via your local network to your device or directly download them on the app via its in-app browser. Now you can open them, view both notes and tablature, and play the song back in various speeds with the option to adjust the volume of single instrument tracks or even completely mute them to focus on one instrument only.

I started practicing with GuitarPro files some years ago on my Mac using an open source reader called TuxGuitar. When I got my first iPad two months ago, I completely stopped learning with my Mac. I did so for several reasons. Firstly, the iPad is way more flexible: my amplifier is placed in the center of my practicing room, meters away from my computer workspace. Additionally, playing at my rounded desk to read the notes on my computer increased the risk of damaging my guitar. Last, the single screen-layout of iOS made me more productive; I wasn’t distracted by any kind of other apps anymore. Unfortunately, this is also the biggest problem with the iPad, too: when you’re on the road without any hardware amplifier, you cannot run both TabToolkit and a digital amplifying software like GarageBand at the same time. Every time you switch from GarageBand with its integrated amplifiers activated to TabToolkit, the monitoring of your guitar playing stops to allow the tablature app to play back the GuitarPro files.

But for band rehearsals, TabToolkit is just a great timesaver. When you’re playing with hardware amplifiers and PAs (without the need for a digital amplifying app) you don’t have to switch anymore – just keep TabToolkit open all the time. With its multi-track layout, where single tracks (e.g. drums or vocal) can be muted, instrumentalists can easily hear what they are supposed to play. If you are not sure how to play a certain part, you can view a note’s location on their via instrument through the on-screen fretboard or keyboard. You can even play back the song in TabToolkit over a PA: just connect it with a cable to the mixer, set the volume, and go.

Sketching and Songwriting

Sometimes you don’t want to play other people’s stuff or your own finished songs – you want to create new ones. How’s that possible on the road? Melodies cannot easily be written down on paper, and making recordings of them is much easier. But you do not always carry your piano or guitar with you… Or do you?

When inspiration strikes, and you’re only carrying the iPad with you, you have to record your ideas with on-screen instruments. Enter GarageBand again. Apple’s music app is the easiest way to quickly record musical sketches. Just open it up, select the on-screen keyboard (or tap to play guitar) hit record, and play. You do not have to care about the sound of any virtual instrument or the bar you’re playing; everything can be changed and cut afterwards.

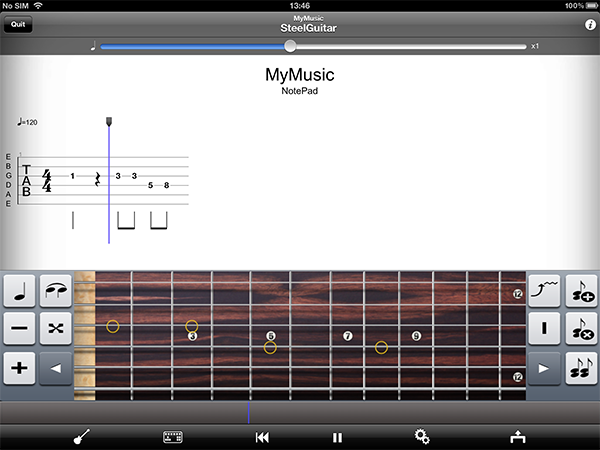

For musicians who are more into writing tablature than recording, there are also several solutions available, with the native GuitarPro app being the most prominent and flexible one. Whereas the desktop version of GuitarPro costs a pretty expensive $60, and has got free competitors like the aforementioned TuxGuitar, the GuitarPro iPad app ($7.99 on the App Store) is the unchallenged market leader for writing guitar tablature and notes on the iPad.

The app’s interface takes some time to understand, but once you learn it, it reveals a very professional and extensive feature set. While viewing tabs is not as good as with TabToolkit, writing music sheets is. In the editing window, instead of a character keyboard, all needed tools are available, and with an intelligent use of gestures, editing, deleting and adding tracks and note is fast and fun. You can load tabs from the mySongBook sheet community or transfer files via WiFi or iTunes from your computer into the app. I wouldn’t recommend creating tabs solely with the mobile version of GuitarPro though. For that purpose it is still not elaborate enough, and you should stick with desktop apps. But to make slight edits to your songs when you’re not at home, GuitarPro is the perfect companion.

On the electronic music side, sketching with software is naturally easier and more affordable, since electronic music is and always was created digitally. An exception from that are analog synthesizers like Moog products — but even Moog is now offering software emulating their analog sound production and mixing processes called Filtatron and Animoog.

In the low-priced category, you can find many drum machines and synths with limited capabilities like Rhythm Studio by Pulse Code. These are apps that seem to be perfect for affordable and easy beat creation. Unfortunately, the interface of such apps is often too skeuomorphic; many developers desperately try to imitate the look of classic drum machines like the TR-808, and fail to do so. In the last 3 years I found only one rather low-priced drum machine app, which fit both my taste in drum sounds and had a usable and iPad-optimized UI: the DM1 Drum Machine by Fingerlab. If you’re interested in how such a music app is built up in detail, read my in-depth review.

Professional creation

With GuitarPro, sophisticated but low-priced drum machine apps with limited features like the DM1, and GarageBand, we’re moving towards the professional music software section. These are the kinds of apps that can make the iPad a standalone recording and creation studio — a mobile center of creativity. Here, we don’t find many different large companies offering music apps, and there are even less smaller, independent ones. As I mentioned in the introduction to this post, KORG is the most prominent example of a traditional hardware manufacturer developing software for mobile devices. They offer several software versions of their controlling and drum machine products including the iconic drum sequencer iElectribe and MIDI controller iKaossilator. These apps mark a peak in single-purpose music apps; they are programmed with love, thanks to intricate details and feature-rich UIs. But they are still only doing one thing each: either creating beats or manipulating sounds. None of the apps I have discussed so far is capable of being everything at once: a customizable drum machine, melodic instrument, sound manipulator, and a multi-track recorder.

The KORG iMS-20 digital analog synthesizer app is. Again, I could have tested several other apps in the same higher pricing range ($10 and higher) like ReBirth (the mobile reincarnation of an iconic desktop software), or Beat Maker (an app which has been available on the App Store for a very long time now). But the iMS-20 beats them all: it’s a 16-step, six-part drum machine with customizable pads; a 16-step analog sound sequencer; a complete synth with on-screen modulation, filters, and effects; and even a cable patch panel to modify specific parameters with oscillators. Plus, it includes a patterned song creation process with mixing capabilities, SoundCloud sharing, and preset downloads to start or get inspiration from. Everything is in one app. Just like with GarageBand, the MIDI connection using the USB Camera Connection Kit makes it work with external keyboards. If your keyboard features a CC (parameter control) mode instead of MIDI notes output, you can use it that way too. Tip: use an iPad stand like the xStand when you’re at home for easier control, and to get the feeling of a real standalone synth.

By featuring both drum machine patterns and synth sounds, you can create complete, multi-track electronic songs with the iMS-20. My first try resulted in an imitation of Daft Punk’s “Around the World” (you can listen to it right here). Given the fact that I’ve never intensely played around with analog synths and patch panels, it sounds quite acceptable, doesn’t it?

There are, of course, more professional creations available online. A good example is from Japanese musician Keishi Yonao, who produced several tracks with the iMS-20, which are available as a preset downloads on the app’s website.

Fortunately, the iMS-20 and other apps priced over $10 aren’t the only ones to offer usable synth sounds and a feature set extensive enough for studio usage. You will find properly designed apps for under $5 as well. A very solid example is the recently-hyped Sunrizer digital analog synthesizer by Beepstreet. Besides 200 pre-installed and over 150 downloadable presets, MIDI integration and an intuitive UI, the app packs a professional sound. I compared both the iMS 20 and the Sunrizer synthesizer’s output frequencies with Ableton Live in order to check if the iPad sound card was capable of boosting out the whole width of frequencies. Both the (quite expensive) iMS-20 and the rather cheap Sunrizer got very good results, even in the quite dangerous lower frequencies (under 100 Hz) — many developers optimize such music apps for the playback with the integrated speakers or mobile headphones, but not high-end studio speakers.

Combining Sounds From Different Apps and Sharing

Now back to the KORG synth again. The iMS-20 also incorporates three wireless features, which are common among advanced music apps for iOS devices: WIST, AudioCopy and Paste, and SoundCloud integration. These features mark my last topic: sharing. Let’s start with WIST.

WIST, short for “Wireless Sync-Start Technology”, is developed and promted by KORG, and allows developers to offer live sync of current settings and patches on two devices running the same music app. This way, you can copy cool sounds, beats, or whatever between two of your iOS devices or to a friend’s device to locally share creations with him or her. This way, you can ensure that you always carry your sound with you, regardless of which device you’re holding; plus, you can connect with your friends and share your work to discuss it with them. WIST is not only integrated in expensive apps like the iMS-20, but also in rather cheap ones like the DM1 Drum Machine.

The second sharing feature, which in my opinion has got the biggest potential for the future, is AudioCopy. Developed and provided by the already mentioned music company Sonoma Wire Works, AudioCopy (and “Paste”) is currently integrated into 104 music apps, including the DM1, iMS-20, BassLine by finger (an app I use very frequently), and Looptastic HD by Sound Trends. Combined with their multi-track recording apps FourTrack and StudioTrack, they established and app community enabling the iPad to do the most important thing for creating innovative music: combining different sounds. With AudioCopy (usually displayed in a small popup panel), you can copy results of your work in single-purpose music apps like your final drum patterns from the DM1, and paste them into StudioTrack to combine them.

With a little trick, this also works with GarageBand (see this YouTube video for the whole process).

Soon after AudioCopy got popular during the Spring of last year, Apple silently integrated it into GarageBand to stay competitive with the large amount of AudioCopy-ready apps. Although GarageBand is not displayed in the “where to paste” list of AudioCopy panels (as it obviously is a big competitor to StudioTrack), it still works. And let’s be honest: GarageBand’s digital amplifiers for guitar recording and its interface are good-enough reasons to stick with it as your mobile mixing and recording studio. You cannot really edit pasted tracks (except from master effects like echo and reverb), but who would export an unfinished song element out of its native app for the final mixdown into another? With AudioCopy, GarageBand, and a bit research in other music apps, your iPad is definitely capable of being a standalone music production environment. There are enough apps to choose your favorite sounds from, and combining them with AudioCopy and Paste and GarageBand as the final mixing environment is easy.

I made two demo snippets for you, completely created and mixed on the iPad to show you what could be the beginning of professionally created music on the go. The first and shorter one incorporates a beat created with the DM1, a bassline I developed with BassLine by finger plus a dreamy guitar improvisation of mine, recorded using the IK Multimedia iRig and GarageBands digital amplifiers. The second, quite long, and a bit monotonous example is a synth arpeggiation out of the Sunrizer synth plus a GarageBand Smart Drum house beat — compare the Sunrizer arpeggio with some of the iMS-20 demo tracks and you will notice that there is not that much difference in sound quality. The iMS-20 is priced higher because it features an additional drum machine, the patch panel, a 16-step sequencer, and integrated preset downloads from other users. But speaking of lead and pad sounds, the Sunrizer is a must-have to extend your tracks with soundscapes and melodies.

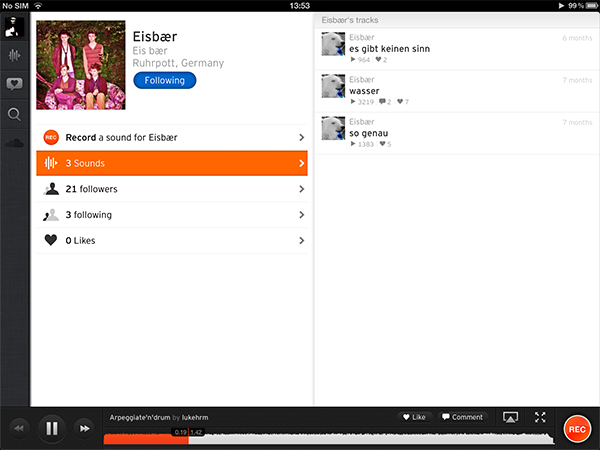

Once you’ve finished your newest masterpiece, you surely want to show it to someone. SoundCloud was and still is the best way to do so, and it’s integrated into more or less every elaborate music app, including Apple’s GarageBand. Just sign up to SoundCloud, connect your account to the app you want to share results from, hit upload, and you’re done. Most of the time you can share the link via Twitter and Facebook afterwards, too. The SoundCloud app for the iPad is well-designed and it’s easy to find interesting, talented musicians who use it.

Wrap Up

This is the current state of music-making and discovery on the iPad. Concluding, I just want to share some thoughts on how this area of software development will continue: none of these features would work without the fast and powerful use of mobile Internet in iOS, because without sharing, discovering and making music would lose much of its convenience. With the right tools and apps, everything is possible on the iPad – whether it is promoting your music, discovering new stuff, learning, practicing or creating. You just have to be passionate — I think none of these solutions can be called 100% intuitive as developers learn the ropes of touch-based music creation and mixing.

The iPad has made many things easier, but it didn’t change one: you have to work hard and experiment with apps and sounds to finally get to a coherent result. Not even the most sophisticated software can replace your mind, your knowledge of music, and your way of interacting with the tools you use. This has always been the case with making music, and I think it always will be.