With the launch of iCloud, Apple is fundamentally challenging the old concepts of computing and “file”, changing the way people interact with computers and devices.

iCloud as a service presents itself as a very straightforward idea: iCloud stores your content and wirelessly pushes it to all your devices. iCloud works with the apps you use every day on your Mac, iPhone or iPad, so you don’t have to worry about syncing your music, photos, documents, contacts and calendars again. iCloud is the evolution of MobileMe, rebuilt from the ground up and re-engineered to take advantage of persistent connections and the concept of “push”, rather than visible, sometimes manual sync. iCloud is not just a big hard disk in the sky, as Steve Jobs joked at WWDC ‘11: iCloud is an invisible service that’s just there, and is now allowing Apple to virtually connect more than 200 million iOS devices.

It just works.

iCloud gives you access to all your music, photos, documents and more without you having to think about file transfers via USB or a manual wireless sync. iCloud is a set of online services that ultimately wants to eliminate the need of a central repository – the digital hub – from where users were forced to start moving content onto other devices, like iPods and iPhones. Ten years ago, when Steve Jobs unveiled the digital hub strategy, the Mac was placed front and center in a plan that would see the desktop computer become the starting point and the destination of our content. The Mac was the hub to centralize media (music, photos, home movies), sync it manually to other devices and peripherals, but it also was the aggregator of new content coming from the iTunes Store, external devices (disks, drives, camcorders) and the Internet. As Steve Jobs noted at WWDC in June, this strategy worked almost flawlessly for almost 10 years: the computer was the “real” machine dispensing content and data; the devices were just external tools meant to receive content.

But eventually, something triggered a deep change in Apple’s digital hub strategy that forced the company to ultimately rethink how users want to buy, download, create and consume content on all their devices. This shift in direction started with the original iPhone in 2007, and was later reaffirmed by the iPad in 2010: these devices aren’t just simple peripherals for passive content consumption. Apple’s new mobile devices – best exemplified by the iOS family – are connected devices with constant access to the Internet, and thus the iTunes Store. Whereas classic iPods wouldn’t be able to connect to the Internet and provide a familiar interface for the iTunes Store – Apple’s storefront for all kinds of content – iOS devices come with iTunes built in as an app, Safari pre-installed and an advanced operating system that, in its latest iteration, bets heavily on powerful features such as Notification Center, PC Free setup, and AirPlay. Apple may still call non-iOS mobile devices “iPods” but, in fact, the motivator and the strength of Apple’s mobile lineup is iOS.

The problem Apple had to face in the past four years is that for millions of people iPhones and iPads have become substitutes to the PC. Over a third of iTunes Store content is now purchased on iOS devices, Apple’s Eddy Cue said at the Let’s talk iPhone media event last week. What started and was celebrated as the hub of the digital revolution became a burden for Apple as millions of customers began using iOS devices as their main devices. Apple was once again faced with a challenge: if people no longer want to use the hub and accept the trade-offs required to manage our digital lifestyle, where’s the new hub? And how will content be distributed in the ecosystem if there’s no visible hub to start with?

The answer is iCloud, and its roots go deep into Apple’s ecosystem. Starting today, there is no hub. Well, technically, there is one and is called iCloud and it lives off a huge data center Apple built in Maiden, North Carolina, but the user doesn’t need to know any of this except the name iCloud and the password required to use it. There is no hub in that there is no old concept of digital hub anymore: there is your music, photos, documents, settings, apps. How they magically appear on all your devices is secondary.

This clip from WWDC ‘11 is all you need to understand the fundamental change behind iCloud. You can find Apple’s keynote video on YouTube, but here’s the gist: the PC has been demoted to just a device. What was once the most powerful machine we’d turn to in order to discover, download and move content around is now on the same level of other devices in our lives. The Mac, iPhone, iPad, iPod – they’re all “just” devices now. Mobile interfaces to a much bigger ecosystem that, thanks to the Internet, makes everything available at our fingertips. The Mac is not gone: it’s got a new role.

The content, if you think about it, has always been there in the cloud. We were downloading songs from Apple’s servers back in 2003 just as I’m pulling an app and TV show from Apple’s data center today. What changes with iCloud is the way we think of how we access content, or rather “don’t have to think”: in the first digital era, the PC was the middle man between the content and the physical device in our pockets. In Apple’s new cloud era that the iPhone pioneered and iCloud is settling upon, there is no middle man as the Internet sends whatever we want straight to our pockets. The content doesn’t need to be shown where to go anymore – iCloud is always the destination.

So what is iCloud, exactly? For many, iCloud will be the operating system. I wrote about the subject back in June, when I tried to explain a non-techie friend of mine what iCloud would mean for her computer and devices in the future – no more USB sync, filesystem and all that. She summed it up as “So iCloud is the operating system”, and that’s actually not too far from what Apple is trying to accomplish by connecting all its devices – even those they don’t make, like Windows PCs – to iCloud. For regular people that don’t write about technology and obsess over the geeky details of things like I do, a computer isn’t what it’s made of and how it works on a technical level – it’s what it does for them. A computer does pictures, email, gets you on Facebook and lets you organize music and movies. A computer stores your media and collects your apps. And here’s where Apple is pulling the biggest trick since the unveiling of the digital hub strategy: iOS devices do exactly the same things. And people like my friend Francesca, it turns out, they buy iOS devices too. So when I tell her that this shiny new iCloud thing Apple is promoting so much is a way to get her photos, music, TV shows, apps, documents and more wherever she wants, on all her devices and for free, obviously she thinks iCloud is “the operating system”.

Because iCloud may not be an operating system technically speaking, but it sure is the operating force behind the system.

Enter iCloud

On a Mac, iPhone or iPad users keep contacts, music, TV shows, apps, personal settings, photos, documents, calendars, email and more. iCloud stores this content, then it automatically appears on all your devices. Because iOS 5 devices come with iCloud capabilities out of the box, people can sign up to iCloud for free, start using a device like they’d normally do, and realize that iCloud makes sure all the changes they make, the apps they download, the songs they listen to are always available on all their devices. Automatically, always and anywhere – these are key features of iCloud. iCloud is automated: there is no sending or downloading. You just do stuff with your apps and iCloud figures out what to make available elsewhere. iCloud is persistent: it’s integrated with the operating system (iOS, OS X) and the web, and it’ll always monitor the apps you use and the documents you create so it knows what to store. iCloud works with all your apps and devices: as long as you’ve entered your account credentials, iCloud makes your data and documents available across multiple devices and multiple versions of the same app. iCloud is convenient and effortless: iCloud works in the background and doesn’t require you to manually sync to get the latest version of your content, or keep track of the latest revision of a file. iCloud pushes it to you, wirelessly.

iCloud is a huge step forward from Apple’s previous attempt at cloud services, MobileMe, mostly because this time it all actually works. In the months that I’ve been trying iCloud with my two Macs, two iPads and iPhone I was impressed with the speed and reliability of the service, both on WiFi and 3G. Gone are the days when MobileMe would accidentally duplicate an entry or suddenly delete a calendar event from your iPhone: iCloud works, and unlike MobileMe, it is deeply integrated with the system.

iCloud works in a variety of ways – most of the time it’s imperceptible and you’d think it’s not working as it should be. But it is, and the fact that you’re not seeing it is perhaps the best thing Apple could ever do since they set out to tear the whole MobileMe architecture apart. iCloud stores content, pushes it, backs it up to the cloud, makes it available anywhere at anytime and it can work with third-party, non-Apple apps too. These features manifest themselves in multiple ways.

When you sign up for iCloud on a Mac or iOS device, right after you’ve added an account (Settings -> Mail, Contacts & Calendars on iOS; System Preferences -> Mail, Contacts & Calendars on Lion) you’re asked what kind of content and settings should iCloud manage for you. On iOS, you’re presented with a series of switches for Mail, Contacts, Calendars, Reminders, Bookmarks, Notes, Photo Stream, Documents & Data and Find My iPhone; on the Mac there are no Reminders (as Lion doesn’t have a native Reminders app – to-dos are synced with iCal) and Notes, but you have Back to My Mac and Find My Mac options. What’s important to understand here is that, whilst Mail and Calendar will effectively give you email and calendar accounts you can configure in other places, all the other options are for storing new or existing app content in iCloud. It means your OS X or iOS Address Book; it means your Safari bookmarks and Mail.app notes; it means the documents and data of any app. The switches and checkboxes you see when activating iCloud are basically a way to say “yes, put iCloud into these apps”.

The practical example works best to describe iCloud’s basic functionalities. When I first set up iCloud, I had an Address Book full of contacts with phone numbers, email addresses and job titles on my iPhone, but not on my Mac or iPad. As I activated iCloud on all my devices, that Address Book appeared within seconds on my iPad’s Contacts app and Mac’s desktop Address Book. Similarly, the Address Book also appeared on iCloud’s web counterpart at iCloud.com, but I’ll get into this in a bit. Once iCloud was up and running, I kept on using my Address Book as I normally would – which means really using it a lot on my iPhone. Thanks to iCloud, all the new contacts I created and modifications I made after the initial setup appeared after seconds on all my other devices. As long as you have an Internet connection, you literally see changes popping up on screen with the iCloud-powered Address Book. Same with Calendar: create an event here, it shows up there. Make an edit on iPhone, it’s pushed immediately to all of your devices. And so forth. You might argue it’s a bit like MobileMe – changes on one device appear on other ones – except it works reliably. And the best part is that there’s nothing to understand or reasons to question Apple’s strategy: why wouldn’t a Calendar event be pushed from my iPhone to my iPad? Of course I want my appointments to show up no matter the device I pick up. And that’s the basic concept of iCloud.

iCloud begins to look more powerful as you realize all the implications behind an always-connected ecosystem of devices. Calendar, Address Book and Mail features are nice and easy to wrap your head around – how about iTunes purchase history though? iCloud has got you covered there, too.

The great thing about digital stores like iTunes is that all customers are treated equally. All the people that buy an item from the iTunes Store are downloading the same copy of a file that is stored in Apple’s cloud. Follow me on this. If I, an iTunes Store user, buy a song through iTunes, per Apple’s terms of service am the rightful owner of that digital copy that can be locally stored on a Mac, PC, iPhone or iPad. With iCloud, Apple is putting the focus on the best feature of digital stores: purchase history tied to a customer’s identity. If you bought it, it’s yours. If it’s yours, you can take it anywhere you want. And because what’s yours is actually a file that’s stored on our servers and you once gave us money for that, we can give it back to you anytime you want if you lost the original copy. At no additional charge. Meet iCloud’s purchase history for iTunes content: all songs, TV Shows, apps and books you bought can be re-downloaded for free at any time. And again, there’s no need to explain it once you get the concept: why would it be any different?

Try to walk into a Gucci store and tell the employees you once bought a highly fashionable purse for your wife. They won’t give another “copy” to you for free because you “once bought it”. If Gucci isn’t your thing, try to do the same at a music store: you can’t have your vinyl twice. But on the iTunes Store? What you buy is a file, not a physical good that requires manufacturing. So here comes purchase history: in iTunes on the Mac or PC and the iTunes Store and App Store apps on iOS you can head over a new Purchased area to browse and re-download all your previously purchased items.

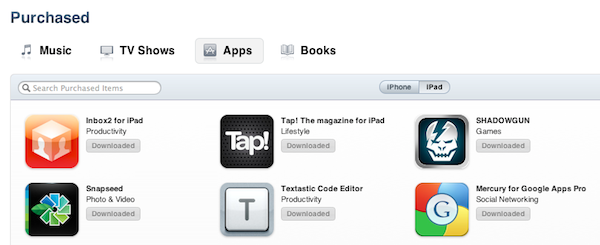

Media that has already been downloaded will have an “Installed” or “Downloaded” label next to it; items that are not on your device will feature a new iCloud button to start downloading them. There are multiple filters to browse purchases (which you can check out in the screenshots above), but the gist is that everything you once bought is available again through iCloud. Yet Apple didn’t stop at making past purchases available again – iCloud extends to new purchases and how they’re pushed across devices.

Past and new purchases have been incorporated into an iCloud feature that Apple calls “iTunes in the Cloud”. This feature will also include iTunes Match when it launches at the end of this month. iTunes in the Cloud works both ways: it gets you past purchases and makes sure new ones are pushed automatically and wirelessly to all your devices. So if you’re on the go and buy a song from your iPhone, it’ll be there on your desktop computer when you get home, already in your iTunes library. And if you’re browsing the App Store from your Mac and you buy an app, the same app will start downloading automatically on your iOS devices seconds after you hit “Buy” on the Mac. This push functionality for new purchases is listed under the Automatic Downloads monicker on iOS and OS X, with options to configure downloads for apps, music and books in Settings (iOS) or iTunes (Mac and PC). Apple has refined iTunes in the Cloud in the past months, ensuring that iPhone apps aren’t automatically pushed to an iPad and both Macs and iOS devices can handle simultaneous downloads of multiple file types. For instance, I bought a song and an app on my Mac within seconds from each other, and iCloud pushed both to my iPhone and iPad at the same time. On my iPhone, I was even able to start listening to the song while it was still downloading. As with Contacts, Mail and Calendar, I was extremely satisfied with iCloud’s push capabilities. I have been using Automatic Downloads since June, and the service has been reliable since the very first beta. And again, Apple has the simplicity of the idea on its side: why would this be any different? Why wouldn’t your music be with you no matter the device?

iCloud permeates every aspect of the operating system and it’s built into the apps you use every day. If you create or edit bookmarks on Safari for Mac, changes will appear on Safari for iOS; when you add a page to the new Reading List, that page will be instantly pushed to all your devices’ Safari browser. Create a note, and it’ll be pushed to Notes for iOS and Mail.app on Lion; buy a book or leave a bookmark on your iPad’s iBooks, and you’ll pick up right where you left off on any other device. Even iMessage, Apple’s new free messaging solution for iOS users, keeps conversations available on all your devices so you can send a message from your iPhone, and pick up the conversation from your iPad. You can see how iCloud’s concept of storage/push represents a big shift in the user experience and overall approach towards the apps that come pre-installed on every Mac, iPhone and iPad. Apple’s message is clear: you shouldn’t worry about losing your data again because the operating system is now capable of effortlessly migrating apps and documents across devices. And for those apps that won’t support iCloud initially, and to make sure content isn’t simply stored temporarily, Apple has created iCloud Backup.

With iCloud, iOS devices can back themselves up to the cloud automatically, so you’ll be able to restore them at any time if things go wrong, without losing any data. And because your purchases (music, TV shows, apps, etc.) are already in the cloud thanks to the iTunes Store, iCloud’s backup system won’t need to upload everything to Apple’s servers – just some data and settings. Here’s what iCloud is able to back up:

- Photos and video in the Camera Roll

- Device settings

- App data

- Home screen and app organization

- Messages (iMessage, SMS, and MMS)

- Ringtones

On iOS, you can take a look at iCloud’s backup options in Settings -> iCloud -> Storage and Backup. In this screen, you can turn iCloud Backup on/off, check your available storage, buy more directly from your iOS device, perform a new manual backup and manage storage.

From the Manage Storage interface you can see how many devices you’ve configured to work with iCloud Backup, see what services and apps are consuming space (like Mail) and, again, buy more storage. If you tap on a device from the Backups list, you can check out what’s behind its backup size, the latest backup date and overall backup size, additional backup options for the data you want to back up and, last, you can delete a backup entirely so it’ll be gone from your iCloud. Now consider the list above – this device Info screen inside “Manage Storage” is what Apple refers to with “Camera Roll and app data”. The Backup Options indicate the apps that will back up their data (their “libraries” or “documents”) to the cloud. But if all your documents and data are always pushed across all your devices, why does Apple need an additional backup layer for iCloud?

iCloud Backup falls under the PC Free category of Apple’s iOS 5 marketing strategy. When Senior VP of iOS Software Scott Forstall announced the PC Free initiative at WWDC ‘11, he told developers how users were forced to take an iOS device out of the box, and connect it to a computer to start using it. iPhones and iPads weren’t really independent from the PC in spite of them being marketed as “post-PC devices”, and this was true for simple actions like activations…or software backups. In the pre-iOS 5 era, users had to back up a device to iTunes through USB. With iOS 5 they still can, but there’s a better option with iCloud. iCloud Backup wirelessly backs up a device’s data when it’s connected to a power source and the screen is locked; this usually means iCloud Backup performs its daily routine at night, when no one else in your house is using the Internet and devices are charging. The next time you’ll need to set up a new device, or restore an existing one with your old data, you won’t have to connect it to a Mac and find the backup file through iTunes on your computer. With iOS 5’s new setup screen, you can simply restore from an iCloud backup, and have all your data automatically pulled from the cloud.

I found being able to forget about iTunes backups and connecting my devices to a computer extremely convenient during the period I beta tested iOS 5 and iCloud. With the final release of the software, I decided to do a clean install of iOS 5 on my iPhone and iPad, use them for a few days, then restore everything from an iCloud backup. The system performed admirably: iCloud Backup was fast (I had to trigger it manually the first time to measure speed) and it reliably set everything back to its previous state after I restored my devices. When setting up a new iOS 5 device, restoring from an iCloud backup requires you to enter your Apple ID and be connected to a WiFi network; iCloud will take a few minutes to authenticate with the Apple ID from the setup screen, then it’ll take you directly to a “clean” home screen. From there, you’ll see apps and data restoring themselves in real-time as if you were downloading them from the App Store. iCloud restore took even less minutes on my network because download speeds are faster, and once the process was done I had my devices in the exact same state I left them after the last backup. iCloud Backup doesn’t let you restore data on an app-by-app basis, and this is done because, as I noted above, apps are already storing their documents in the cloud. iCloud Backup is a single convenient solution for when you need to set up a device after a restore.

iCloud may not be a big hard disk in the sky, but Apple knows that there’s no cloud without storage. That’s why iCloud comes with a free 5 GB plan for all users and additional pricing plans to purchase more storage. However, Apple wants you to pay attention to how iCloud works – because apps, TV shows, music and books are already stored in the iTunes Store, they won’t count against your initial 5 GB. Photo Stream, a new feature to store your latest 1,000 photos in the cloud, doesn’t count against the free 5 GB either. Your mail, documents, Camera Roll, account information, settings, and other app data will consume iCloud storage, but they likely won’t consume much because data doesn’t eat as much space as media. This leaves enough room for iCloud backup on multiple devices and third-party apps with their iCloud documents & data; still, Apple has created a new menu to buy additional storage at a price if you can’t go on with 5 GB.

We detailed iCloud’s international pricing plans in this article; Apple has also put together a chart for Storage Upgrade Options on its website for multiple currencies. There’s the chance you’ll never need the $100/year 50 GB plan (55 GB total iCloud storage), unless you really keep heavy backups and have apps storing GBs worth of data in the cloud. That’s a rare scenario. For most users, iCloud with 5 GB of free storage will be enough for data and backups. And again, media from the iTunes Store won’t count against the free 5 GB, so iCloud represents an interesting solution to balancing local storage (music, TV shows, etc) with available online space.

Whereas iCloud’s app data will always be exclusive to iOS and Mac apps that have chosen to integrate with iCloud, a few core functionalities of the service have been ported to the Web, which works on any device as long as it’s got a modern web browser. The iCloud.com web apps, originally launched for developers earlier this year and now open to the public, provide a nice alternative to reading your email and accessing your contacts, calendars and iWork documents on iOS or OS X. iCloud.com offers a limited set of tools that largely replicate the appearances of their mobile and desktop counterparts, with the obvious advantage that they work anywhere because they are written for the web.

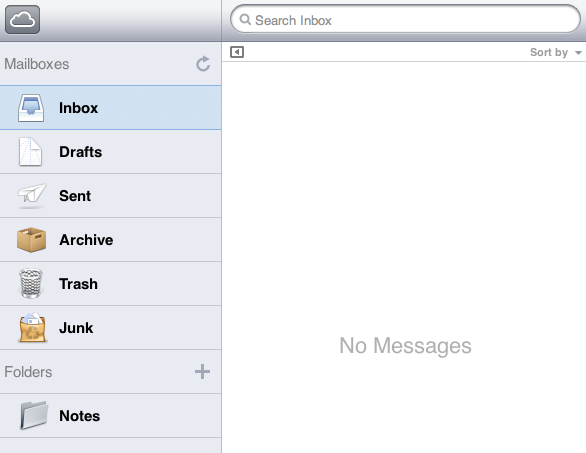

iCloud.com’s Mail application looks like the iPad version, behaves like Lion’s Mail.

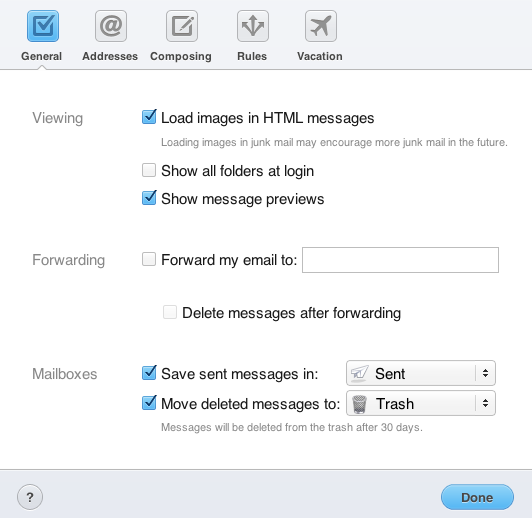

Mail preferences on iCloud.com.

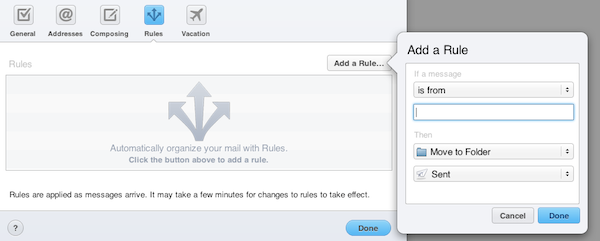

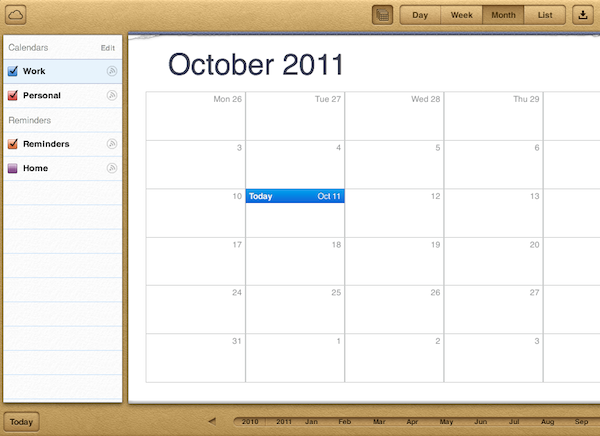

On iCloud.com you’ll find Mail, Contacts, Calendar, Find My iPhone and iWork. These web apps work and (most of the time) look exactly like Apple’s iOS and Mac apps, with a very few exceptions. Mail, for instance, is a mix of Mac and iPad graphical elements: the app has the same widescreen-based layout of Lion’s Mail, but the UI chrome is clearly borrowed from the iPad. There’s a sidebar with your Inbox, Drafts, Sent Messages, Archive and Folders, and just like Lion’s Mail you can hide it at any time to focus on the task at hand. You can search your inbox, sort messages with various options and do anything you’d expect from Apple’s Mail application. You can even create and manage basic mail rules to automate the process of deleting/moving/forwarding messages coming from a specific address or containing a specified subject. The email web app has got a series of Preferences to customize, so you can set viewing and forwarding behaviors, add email aliases and personalize email composing options.

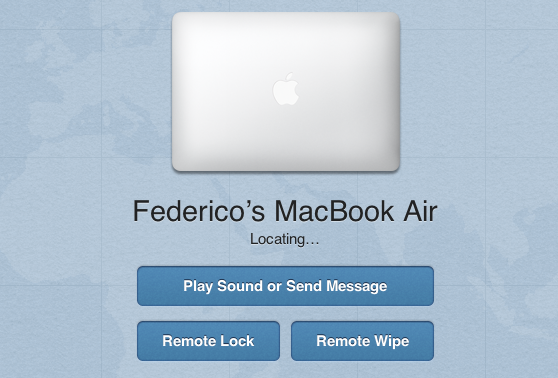

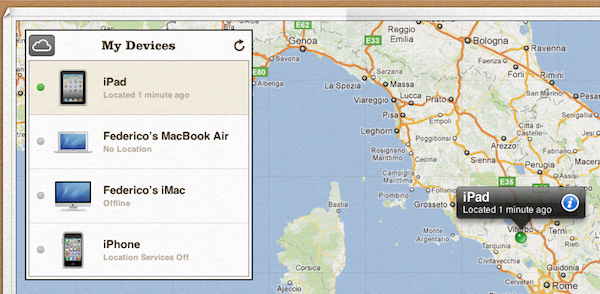

If you’re already familiar with Apple’s core applications you’ll know how to use the iCloud.com web apps. Contacts and Calendar look and work exactly as the apps for Macs and iPads; Find My iPhone simply has a redesigned UI for the same set of commands and features of the Find My iPhone iOS app. There isn’t a thorough explanation of iCloud.com web apps on Apple’s website because there’s no need to explain anything: they’re really the same apps you already know, only written in markup language for the web, with redesigned preference panels and dropdown menus that you can check out in our screenshots, or by hitting iCloud.com with your iCloud account.

iCloud.com web apps mirror the looks and functionalities of their native counterparts. But that’s not to say they’re useless. I haven’t used iCloud.com much in the past months, mainly because I always have my Mac, iPhone or iPad available at my desk or in my bag; I do recognize, however, that for people that can’t always take their Macs with them at work or on the go having access to beautifully designed apps with all your data is a huge plus. I believe that most people won’t need to use iCloud.com, but those who will are going to love the web apps and rely on them on a daily basis. It’s always nice to have options – Apple understood this with iCloud and rebuilt the old MobileMe web apps from scratch throwing away all the old code, making the apps beautiful, reliable and faster. Furthermore, iCloud.com offers a useful “View Account” menu (again, inspired by iOS) that you can use to set a profile picture, language, time zone, view your Apple ID and manage advanced settings. The attention to detail in this Preferences window is fantastic (try picking a language or time zone).

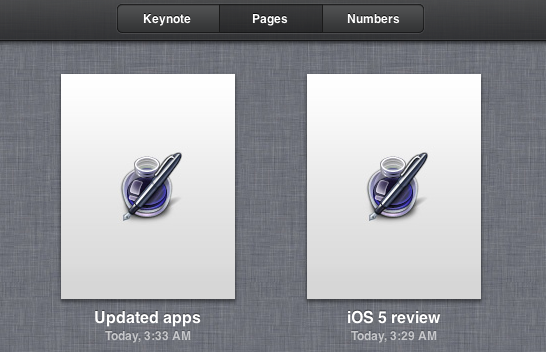

While we’ll have to wait for third-party developers to update their apps to take advantage of iCloud’s document storage (Mac apps will be able to sync data across multiple Macs, and different versions of the same iOS app will do the same across iOS devices), Apple has already updated iWork for iOS to work with iCloud’s Documents in the Cloud, and the first visible result of this update is available on iCloud.com as well. The new iWork apps for iPhone and iPad can push new documents as well as changes to existing documents in real-time through iCloud. So if you’re editing a document in Pages for iPhone, that document will be automatically stored in iCloud and pushed to your iPad and you’ll be able to pick up right where you left off. The new iWork for iOS is impressive in how it easily and effortlessly registers and pushes changes through iCloud, but even more impressive is how documents stored in the cloud show up correctly in a web browser on iCloud.com.

Apple may be killing the concept of filesystem with iCloud’s push technology on single app basis and lack of iDisk, but the company knows people like to have documents available anywhere for editing, copying and deleting. So right on the homepage of iCloud.com, there’s a big icon for the iWork web app, which unlike the others doesn’t offer a complete working alternative to native iOS and Mac apps, but only a way to see the documents being stored in the cloud. You can’t edit a Pages file on iCloud.com – Apple’s hasn’t built its own version of Google Docs with online editing and automatic saving (yet), and it’s not clear if and how iWork.com will be merged in iCloud.com. On iCloud.com, you can see the documents that are being stored by iWork for iPhone and iPad, duplicate them, delete them, download them on your computer, and upload new ones through your web browser. Any change you’ll make on iCloud.com will appear on iOS devices, but unfortunately until Apple builds a proper web app for iWork this means you’ll have to download a file locally, edit it with iWork for Mac, and upload it again to the browser. Even more surprising is the lack of a Mac version of iWork that’s directly integrated with iCloud, but I assume Apple is already working on iWork ‘11 with native iCloud support. Otherwise this wouldn’t explain what looks like a temporary solution – having a middle man that uploads files for iWork on OS X, and can’t edit documents online on a PC. Still, the technology behind the current version of iWork on iCloud.com is very efficient: file changes are pushed quickly across devices, and new uploads take seconds to propagate across iPhones and iPads.

What’s unclear is whether Apple, going forward, will allow third-party developers to make their apps “recognizable” by iCloud.com. Right now, developers can take advantage of the iCloud APIs to build Mac and iOS apps that store documents in the cloud and push them wirelessly to all your devices. But in a future not too distant from today, will these documents be able to show up on iCloud.com, like iWork? I don’t think Apple will ever let developers build their own web app alternatives for iCloud.com, but I believe it’d be nice for say, Notely, to be able to have its .txt files available in a Notely tab on a universal “Documents” app for iCloud.com. If not for online editing, simply for downloading and uploading like iWork does, so users will have the possibility to download supported documents from iOS apps on their Macs and PCs. I have tested a few third-party apps with iCloud support ahead of iCloud’s launch, and the change in usability is dramatically good: iPhone apps share the same documents of their iPad versions and changes are immediately visible on all devices. Yet for apps like Notely and Elements, text editors that work with universal file formats and don’t have native Mac counterparts, it would be an interesting option to have their documents also available on iCloud.com (these apps already sync with Dropbox). Perhaps it’s a broader issue with accepted file formats and sandboxing – I don’t know what Apple is working on and the third-party iCloud ecosystem is just getting started. But I’ll keep an eye on iCloud.com as a way for making documents always available, rather than just mimicking Apple’s desktop apps. The web’s potential is unlimited and it feels like Apple still hasn’t fully explored the possibilities of web access with iCloud.com and Documents in the Cloud.

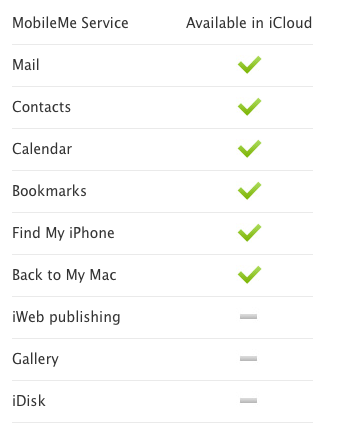

There are other aspects of iCloud and iCloud.com that I’d like to address with this overview. First off is MobileMe migration, which Apple explained earlier this year with the developer beta of iCloud but that is set to undergo some changes now that iCloud is open to the public. The basic process remains the same: Apple says that any active MobileMe account can be transitioned to iCloud. After the migration process your me.com or mac.com address, your MobileMe mail, contacts, and calendars, as well as your bookmarks will be available in the new iCloud service. Other old MobileMe data and apps like Gallery, iDisk and iWeb won’t be available in iCloud, but they’ll be kept around until June 30, 2012, when MobileMe will officially stop working. Apple has already explained the process in this support article and we covered it here.

Active MobileMe subscribers can migrate to iCloud through a simple in-browser process by visting this webpage.

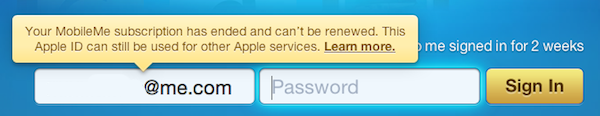

An inactive MobileMe account can’t be renewed and moved to iCloud.

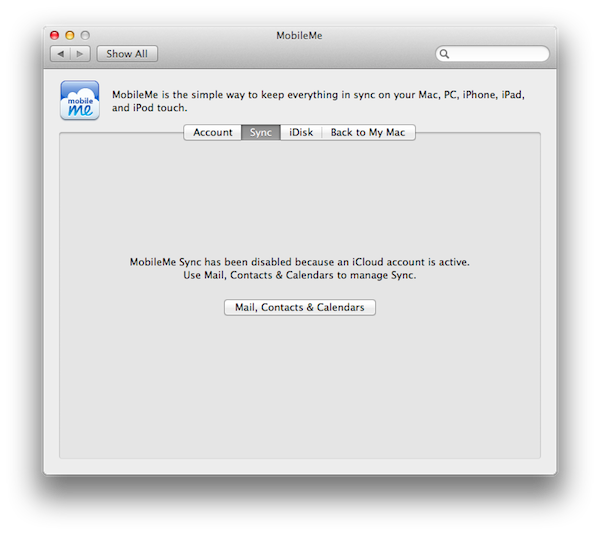

The MobileMe preference panel on OS X is disabled if another iCloud account is active.

We also published a basic overview of the MobileMe -> iCloud transition when it went live for developers this summer. Apple has made sure that active MobileMe accounts as of June 6, 2011, will be automatically renewed until June 30, 2012, at no additional charge. My previous me.com account was, in fact, successfully moved to iCloud with all its data and 20 GB of storage for free until June 30, 2012, when Apple activated the transition process for developer accounts in August. A MobileMe account used to cost $99 per year with 20 GB of storage; iCloud is free and gives you 5 GB of storage with additional upgrade pricing. What may be subject to change is Apple’s intention to let users merge iTunes and MobileMe accounts; whilst technically possible to keep purchases and data under a single Apple ID, many users often end up having separate accounts for iTunes Store purchases and MobileMe. Apple’s support document on the matter says it won’t be possible to merge accounts, but the company has been rumored to be considering the functionality. Fortunately, iOS 5 lets you enter separate Apple IDs for your Store purchases and iCloud. Apple details the process in this support document.

I recommend keeping an eye on Apple’s MobileMe transition Q&A and this support document to learn more about migration, MobileMe refunds and Apple ID management.

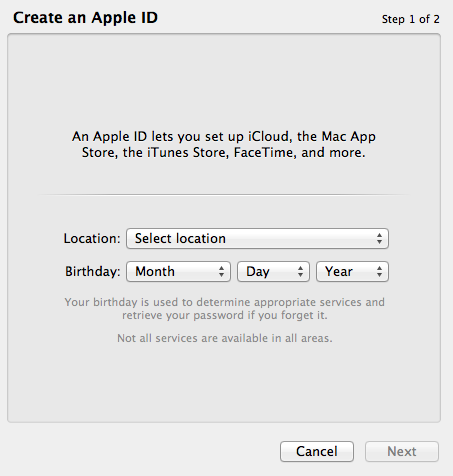

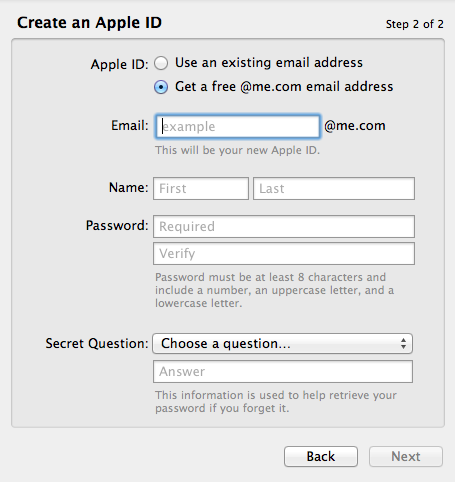

Starting today, users can create a new me.com account with iCloud support. To do so, open the Mail, Contacts & Calendars preference panel on your Mac or iOS device and start by adding a new iCloud account; your device will ask you to log in with an existing account, or get a free Apple ID to start using iCloud. The procedure to create a me.com Apple ID is very simple, and once done you’ll be able to use this Apple ID for iCloud, iCloud.com, the iTunes Store, FaceTime, iMessage and more. When setting up iCloud on your device for the first time, the OS will ask you if you want to merge existing device data with iCloud; if you agree, your contacts, calendars and other app data will be pushed to iCloud.com and other configured devices.

Additionally, Apple has launched a nice iCloud Setup page that details the necessary steps to get iCloud up and running on iOS, OS X and Windows PCs. A Get Started page is also available here, listing the basic software requirements for iCloud.

iCloud comes with Photo Stream, a new feature to store your most recent 1,000 photos in the cloud and have them available all the time on all your devices. I believe Photo Stream will be the new functionality that early iCloud adopters will immediately “get”, as it’s built for simplicity and extreme usability. More importantly, it fixes a long-standing annoyance of the iOS ecosystem – photos taken on an iPhone would need to be manually synced to a Mac, and a computer’s photo library wouldn’t automatically show up on an iPhone or iPad. Photo Stream fixes this: as I previously detailed here, it keeps your most recent additions to the iCloud photo library available on all your devices, including Macs and PCs. iCloud doesn’t come with its own Gallery application, but because iCloud is integrated with all your apps, all your devices contribute to iCloud’s Photo Stream: your iPhone pushes photos to iCloud, your iPad does, your Mac does, and your PC does, too. All your devices are able to push and receive photos from iCloud, with performances that may be described as almost real-time depending on your Internet connection.

Imagine the following: you’re out with your friends, and you take some pics with your iPhone. You come back home, open iPhoto on your Mac, and the photos are already there. Or you pick up the iPad from the comfort of you couch, and the photos are already there as well. Perhaps you like to have fun with your kids in Photo Booth for iPad – when you’re at the office and you want to show those photos to your colleagues, they will be there in your iPhone’s Photo Stream. iCloud’s Photo Stream works in the background both if it’s pushing photos to iCloud or receiving them. You can’t manually refresh Photo Stream, which is built into the Photos app for iOS and iPhoto on the Mac. You can’t even delete or edit photos from Photo Stream, as you’ll have to save them locally first to make any changes. Photo Stream is a continually-updating album of your most recent photos, organized for efficient storage (1,000 most recent photos for the past 30 days are kept in iCloud) and usability (“it’s just there”). Photo Stream doesn’t require any management once it’s up and running, and if you’re using it on iPhoto for OS X you’ll also notice that it automatically saves previous Photo Streams as events in your local library, so you won’t lose photos when the Stream is cleaned up of old entries.

Photo Stream gets your photos everywhere, and it’s deeply integrated on the desktop. iPhoto and Aperture can push new photos added to their libraries to Photo Stream, so your latest DSLR shots will be available on mobile devices; and if you want to check out your latest photos on a bigger screen, Photo Stream has been ported to the Apple TV with the same technology used on iPhones and iPads. I have been testing Photo Stream since June, and I love it. I’m constantly taking screenshots and photos on my iPhone – which is my main camera – and being able to find them after seconds on my Mac’s desktop has greatly improved my writing and, overall, photo editing workflow. We’ll see how Photo Stream performances will hold up over time as more people begin using iCloud. But right now, Photo Stream is another (and perhaps the best) example of iCloud’s “it just works” philosophy.

For those people that will look for an iDisk/Dropbox alternative in iCloud, it’s likely that they’ll have to keep looking. As previously announced, Apple is discontinuing iDisk’s folder syncing functionalities and it won’t emulate Dropbox for seamless desktop and mobile sync of files and folders. At least not in the near future. I’ve already discussed the implications behind iOS and the traditional filesystem before, and I’m not looking to get into this again, but here’s a quick recap: for Apple, it’s all about the apps. The apps, not folders, contain the data you care about on your devices. Your songs are in iTunes, photos are organized in iPhoto, documents are stored in iWork. This library metaphor has been carried over to the latest version of iOS and iCloud. Apple has been shying away from filesystem-based solutions for quite some time now, and it doesn’t look like they’re willing to re-imagine the app-driven document model anytime soon. In the meantime, you can always use the hundreds of apps that work with Dropbox.

Last, I’ve collected various notes of interest about iCloud from Apple.com:

- Backup of purchased music is not available in all countries. Backup of purchased TV shows is US only. A purchased item may be unavailable to be restored if it is no longer in the iTunes Store, App Store or iBookstore

- iCloud is available worldwide. iTunes in the Cloud varies by country. iTunes Match and TV shows are US-only. iTunes in the Cloud and iTunes Match may be used on up to 10 devices with the same Apple ID

- Using iCloud with a PC requires Windows Vista or Windows 7; Outlook 2010 or 2007 is recommended for accessing contacts and calendars.

- Photo Stream is compatible only with the second-generation Apple TV

- Recommended browsers for accessing iCloud are: Safari 5 (or later), Firefox 5 (or later), Internet Explorer 8 or later, Chrome 12 (or later)

- To switch applications on iCloud.com, you can also press Shift–Esc on your keyboard, and use the Arrow keys to select a different application. When the application you want to use is selected, press Return (or Enter)

The Truth Is In the Cloud

iCloud changes the way we interact with our devices. Ten years after the digital hub revolution led by the Mac and iPod, Apple’s ecosystem has evolved and turned into a variegate selection of notebooks, desktop computers, iPhones, iPods and iPads. iCloud goes beyond the simple function of a new digital hub: iCloud, built into iOS 5 and Lion, is the new soul of Apple’s hardware that unifies music, videos, photos, apps, books and documents. iCloud is a huge change for Apple’s ecosystem not just because of its new technology – it’s a new software paradigm that will deeply affect Apple’s devices and how we work with them in the next years. Ten years from now, when it’ll likely be time for another digital revolution, we’ll look back at 2011 and iCloud’s launch.

iCloud’s immediate strength as users upgrade to iOS 5 is its integration with the apps we use every day. There’s no learning curve – iCloud isn’t replacing old apps and iOS standards, it’s working alongside iOS to provide a better user experience across multiple devices. iCloud performs the double function of improvement for Apple’s core applications and new underlying foundation for third-party apps, which starting today will get access to the same cloud features that Apple is using to sync documents and data in its system apps. With iCloud, Apple understands that, for the user, third-party apps aren’t less important than first-party software. iCloud democratizes the App Store ecosystem in making the cloud available to everyone.

iCloud was Steve Jobs’ last product launch at WWDC 2011. Unsurprisingly, it’s also the software platform that will shape the future of iOS and OS X.