Oliver Cameron thinks there’s something special, intriguing, about the address book. As a personal list that smartphone users have curated over several years, one could wonder about the stories, the people, and the interactions that are part of the creation and curation of an address book. But what can software developers do to leverage the data of our address books to redefine the way we get in touch with our closest friends?

Over the years, digital address books have exponentially increased the amount of data associated with names and phone numbers. First came dedicated fields for email addresses and contact pictures; then, when smartphones gained decent networking and data connections, the address book turned into a richer solution to store people’s information, rather than just addresses, and keep it always accessible on multiple devices through the cloud. Either through Gmail, Exchange, iCloud, or something else, it’s very likely that your address book contains names and phone numbers, but also email addresses, Twitter and Facebook usernames, location data, birthdays, family relationships, and various notes. The address book is, in fact, a people database that’s exclusive to each person. There is no address book like each other.

While the composition of an address book differs from user to user, some interactions and relationships are reflected on multiple instances of the address book, and the cloud can sometimes access a portion of these interactions to create lists of people “you may already know”. If I have you in my address book as a “friend”, maybe I also have your email address, and perhaps you have my information on your address book as well. With the right privacy settings, services like Facebook, Twitter, and just about any app with a social component these days allow us to look up friends that are already signed up by simply matching email addresses. This is a way to leverage the information stored in our address books to facilitate the sign up process for new services. They make it easier for us, using the address book we have been curating over the years.

Sometimes, however, people don’t want social apps that force them to share with everyone. Services like Twitter and Google+ are the polar opposites when it comes to determining how users engage with each other: whereas Twitter’s model of following/unfollowing may result overly simplistic to some people, Google’s insistence on Circles has found users confused by the plethora of options Google+ comes with. And then there’s Facebook, which has been experimenting for years with the concept of private groups, albeit they never really took off, and so Facebook preferred implementing deeper privacy settings, rather than forcing people to manage groups and names and lists. But is there a sweet spot between Twitter’s simplicity, Google’s circle management, and Facebook’s wide adoption both on desktop and mobile? Something that can leverage the data from our address books and social networks we’re already using to build a new platform to bring us closer to the people we know “in real life”? That’s what Oliver Cameron and his team are trying to build with Everyme.

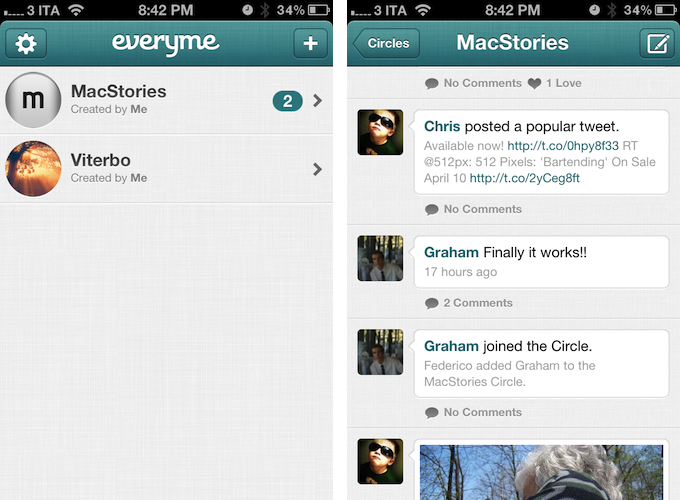

Free, and available on the iPhone today, Everyme is a new app that aims at allowing users to communicate with friends and family through Circles. Everyme wants to help people keep in touch with friends, co-workers, family members, or high-school friends they actually care about. And it’s doing so by recreating a common behavior among human beings: the creation of circles of people.

Cameron told me he thinks the current state of sharing on social networks is fundamentally flawed. Because human beings often don’t like to expose themselves too much in regards to the things they like or don’t like, or the opinions they have on a particular subject, they are somewhat forced to change the way they share on social networks to avoid hurting someone else’s feelings or opinions. By nature, human beings tend to create small groups of similar individuals that, in spite of their differences, share common interests or traits. Without getting too much into human psychology or antropology, I think we can all relate to the fact that, every day, we share the important things we care about only with the people we choose.

From a social network’s perspective, web services have tackled these human behaviors with different mechanics. Whereas Twitter has based its growth on the concept of “following” someone because you like the things he has to say (that’s why many tend to share just about anything on Twitter), Facebook has more of a “personal” approach to sharing, in that the whole idea of “friending” someone implies, to an extent, that you don’t want to cause any trouble by publicly sharing things that may be controversial. I, for one, never talk about politics on Facebook. Why? Because I know some of my “friends” may not agree with my opinion and thus we may have to enter a discussion that no ones want to see on Facebook. And it’s very likely that I’d do the same in real life: at a bar, I’d probably avoid mentioning my take on politics with that person. With another friend? I’d go ahead and talk about it – but Facebook doesn’t allow me to easily share something publicly, yet only with a selected number of people. Sure, Facebook has made some amazing progress in letting you select how many people will “see” what you’re sharing (and they also implemented Twitter-like subscriptions), but, personally, I never feel safe about the filters generated by Facebook. What if they mistakenly put someone else in my high school group? I think the big problemn with Facebook and groups is that, because the company never really believed in them, people “got used” to filter their own items to share and now they go ahead and choose Public any time. By slowly improving groups, Facebook still can’t win many users’ trust back, because they are now used to think of Facebook as “share with all your friends” or nothing.

Everyme wants to tackle sharing with a private group of people head-on from Day One, and its developers want to make sure the creation and management of circles don’t require the same amount of manual effort of Google+. To do so, they are leveraging data from Twitter, Facebook, LinkedIn, and the address book.

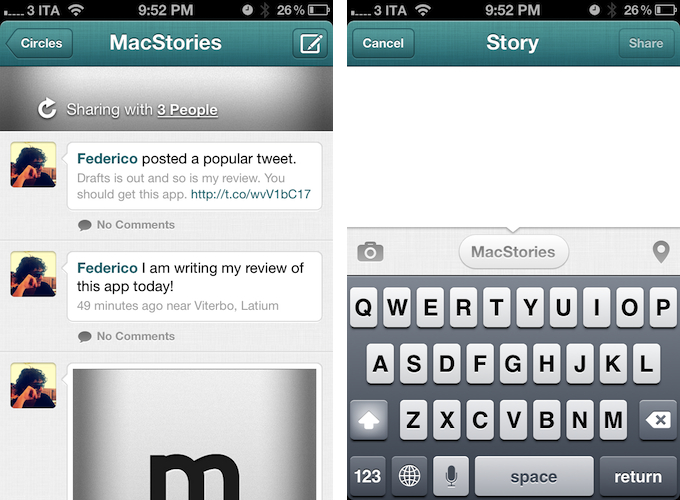

The groups of Everyme are called “circles” – like Google+ – and they are a private feed only you and the members of the cirle can read and interact with. Within a circle, you can post text updates, photos, location information, and change the cover photo. This pretty much covers the basics of Everyme, and I could end this review saying that Everyme is a pretty solid and polished app to keep in touch with different groups of people outside of the usual Twitter and Facebook social spheres.

How Everyme tries to build better circles, though, is interesting. To avoid the manual process of building circles as seen on Google+, Everyme connects to your Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn accounts, as well as your address book, to figure out on its own people that you a) may already know and b) may belong to a particular circle. This automatic circle building process is aptly named “Magic Circles”, as the app uses its server-side algorithm to match people’s names, usernames, phone numbers, email addresses, location, and more to provide a series of “smart” circles right after you’ve signed up. Following the recent controversy with Path, Everyme has even implemented a dedicated dialog that clearly explains contacts are never stored on the servers, but are used to match people with each other.

Magic Circles are important for two reasons. First, they obviously offer a (at least partial) fix to the problem with group-based messaging tools that force you to manually build your groups, starting from scratch. If services are so connected nowadays, why can’t they pull their magic and figure it all out for me?

Second, Magic Circles prove that, by aggregating data through OAuth and doing some clever server-side matching, today’s services have an amazing amount of data about ourselves and our social connections that could be used to improve the way we communicate. Everyme has simply chosen to apply this system to groups of people sharing things online.

In my tests, once connected to Twitter and Facebook and given access to my iOS Address Book, Everyme built two Magic Circles for Viterbo (my town) and Liceo Classico Mariano Buratti (my former school). I was surprised to see how the app correctly picked people, I assume, from either the address book or Facebook, correctly “assigning” them to the group they belonged. Obviously I couldn’t test any of this because the app was a beta my friends couldn’t access, but it showed the promising concept that Everyme hopes will become a standard in the future. Once I created a new circle, I invited my fellow MacStories writers, and we started sharing things privately, between us, knowing that no one else outside that circle would read them. From a design and basic usability perspective, Everyme is intuitive and easy to use. There are circles in the main page, and you can change their cover photos; you can receive push notifications for when someone comments on a story or posts a new one; you can comment, share text or photos, or “love” others’ stories. You can manage people within the circles you have created, and update your profile at any time from the Settings.

Everyme has two other clever functionalities that will hopefully contribute to helping people “remember” about the app. A common problem with new social layers and apps is that early adopters often forget about them after some time; they also don’t make it as frictionless as possible to share stuff. Unlike other networks, Everyme makes it easy to comment on stories even if you don’t have the app by replying via email or text message (I haven’t been able to test text messages from Italy). In fact, the app wants you to enter as many phone numbers and email addresses as you want to make sure you’ll always be notified of important stories in your circles. Which brings me to the second standout feature, Magic Stories. Like Magic Circles, Magic Stories uses data from social networks to automatically build content you may be interested in reading. While Magic Circles handles the creation part, Magic Stories looks at Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn updates to notify you of events it deems relevant. These events can be a popular tweet, a birthday, an office promotion, or a friend who has broken up with his partner. In my tests with a very limited number of people, it was nice to be notified (Everyme supports push notifications) about Chris’ re-release of Subtle Papers II; this tweet of mine was also marked as important. I don’t know the exact specifications of Everyme’s algorithm to determine Magic Stories, but I assume it looks at the number of comments, retweets, faves, and likes an item receives, as well as other data points like status changes and birthdays.

As with many new social products nowadays, we have to make a distinction as to whether Everyme is a fine app that will succeed. As an app, Everyme is a good piece of software: it looks okay, it’s stable, updates fast, and it can feel instantly familiar to anyone who’s ever used a messaging app or Twitter client. But will it be successful, business-wise?

Now that’s a trickier question. Everyme is free, and it has raised capital from some investors, including CrunchFund, to make sure it can maintain operations and build on its concept. As Instagram shows, “success” these days doesn’t necessarily seem to imply a business model (e.g. making money) is required to become popular: in fact, many argue that it’s the very nature of free that has allowed products like Facebook, Twitter, and even Instagram to take off in the first place.

Like Google+ demonstrates, the real issue with new social apps is adoption. Without users, the lack of a business model only adds up to the bigger issue of a lack of people using the app, and that’s what Everyme is trying to address with automatically generated circles and stories. Let the content come to the user, not the opposite. This isn’t too dissimilar from Instagram supporting a variety of social networks for sharing pictures, but Everyme needs more to really reinvent and optimize private messaging between groups – it needs to be cross-platform for people who don’t have iPhones. Instagram took off with just an iPhone app; I’d argue that the market for private messaging that leverages address books and online services could be even bigger. Fortunately, it appears the Everyme team knows messaging services need to be ubiquitous – the initial support for text messages and email replies is very nice and promising. But, let’s not forget there’s always the huge shadow of Facebook looming, and of course Apple’s own iMessage protocol, now in beta on the Mac as well. Everyme must invest on its unique features to stand out from this crowd.

Everyme is a private “network” of people, organized in circles, connected to other services. The distinction between “communication” and “sharing” will also define Everyme as a private network, or a messaging service going forward. Unlike most messaging solutions, Everyme could improve its “magic” aggregation and cross-service data collection to simplify organization for its users; unlike most social networks, Everyme could, say, think of something like Xobni’s contact history to provide better, more informative stats about the people you care about. It is an interesting scenario, and I look forward to Everyme’s next steps; today, I don’t think Everyme can be compared to Path – as some are already doing – as the focus is clearly on group messaging, whereas Path has taken a more elegant, Facebook-like approach with its digital journal.

For now, Everyme is a fine app that works with the three biggest social networks (and your address book) to offer a new take on private group messaging/sharing. You can download the app here.