In my daily workflow, I rely on Alfred for Mac to find files, folders, and apps for me. Since July 2012, I have used Alfred 4,326 times for an average of 46.5 times a day. I use Alfred for a variety of tasks which include (but are not limited to) accessing favorite folders, launching Google search, acting on multiple files through the Buffer, and executing AppleScripts. Alfred is one of my favorite pieces of Mac software, ever.

I like launchers. They simplify my workflow while allowing me to save time and be more efficient. This is why I’ll keep an eye on the development of Shortcat, a new Mac app – currently in public beta – that aims at becoming a launcher for interface elements.

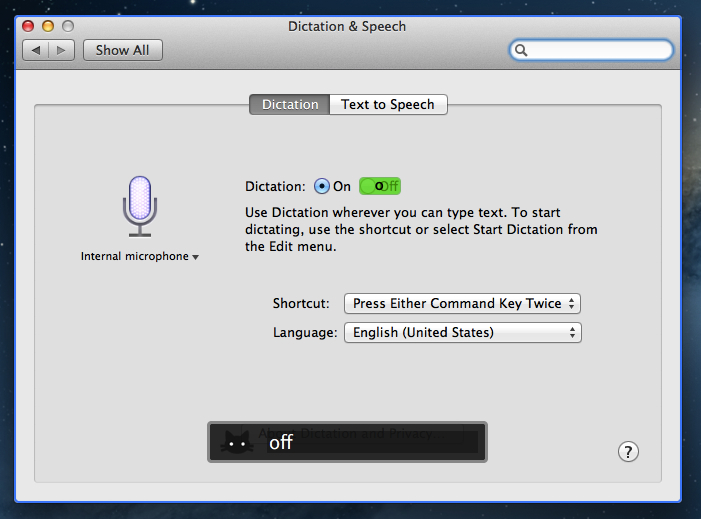

The developers describe Shortcat as “Spotlight for the user interface”, and that’s a fairly accurate description. Essentially, Shortcat relies on support for Assistive Devices (an Accessibility feature of OS X) to be able to “see” the labels of buttons and menus and “click” on them. So, for instance, instead of moving your cursor on the trackpad, you’ll be typing “back” to make Shortcat click the Back button in Safari.

Shortcat works better with apps that leverage Accessibility features and have properly labeled buttons and interface elements. In the app’s Help menu there’s already a list of apps that don’t work properly with Shortcat as it’s unable to “read” (and thus let you find) their interface elements. I am no Accessibility expert, but my guess is that these apps don’t support VoiceOver either.

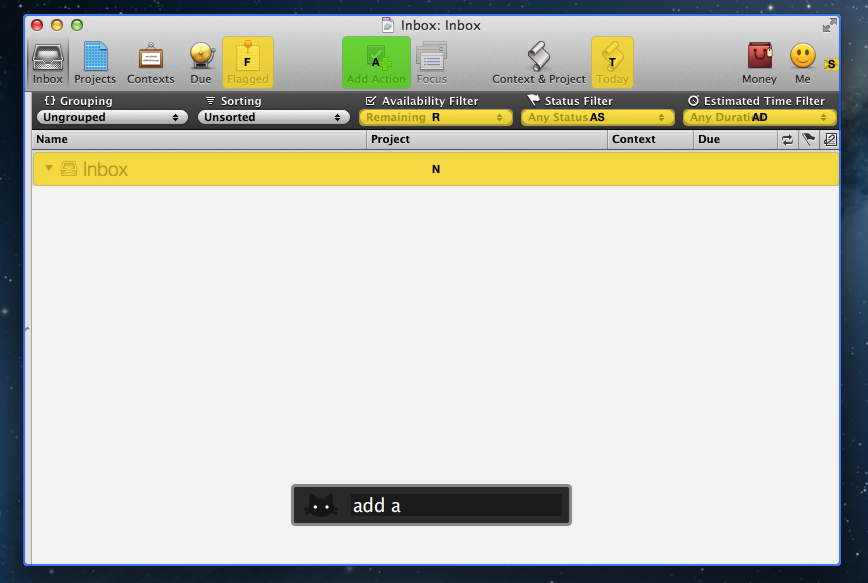

In my tests, Shortcat was a pleasant surprise. If you don’t know about Accessibility, the app will look like a fantastic trick – how can it click for me when I’m just typing? In actual usage, there are some things to be considered. When you invoke the app with a shortcut (it’s customizable from the Terminal in this version) and you start typing, it will highlight areas of an app that match the letters you typed. The best match is highlighted in green, other possible “destinations” for the mouse are yellow. You can click on a button or menu by typing its full name or an abbreviation, such as “Add Action” or “AD” for the toolbar button in OmniFocus.

You can also tell Shortcat to show “hidden” results. By preceding your query with a dot, you’ll be able to reach interface elements that, at first glance, don’t have a label. I tested this with several apps, and, for instance, I was able to type “.1p” to click on the unlabeled 1Password extension in Safari, or “.n” to open the compose box in Tweetbot. Speaking of Safari, you can also use Shortcat to click on website navigation elements such as buttons or text. “Clicking” on hyperlinks with Shortcat will, just like a regular click, open them in a new tab.

Shortcat is an interesting experiment, but it needs more work before being ready for primetime. Its text matching algorithm is good, but still not perfect: sometimes, it associates things like “SYNZ” to “sync”, which isn’t particularly nice to see. I would also like to see a more polished graphical representations of highlights and selected regions of the UI, as right now the highlighting process seems more a “hack” than a consumer product. Also, I’m still not completely sure how, in every day usage, Shortcat could come in handy. Is it a utility to navigate large documents without typing? Or is it an app navigator? In a world of buttons associated with keyboard shortcuts, are virtual clicks really that necessary? Shortcat makes for a cool demo, but it needs to find a stronger message to make people “get” what it’s all about.

You can check out the Shortcat beta for free here.