I believe people aren’t using iPads only as devices to “watch videos” or “catch up on reading”. Perhaps many people are; but there are some individuals who, thanks to the power and portability of the iPad, have managed to fit the device into their workflows and personal lives in ways that most of us wouldn’t expect. I think these stories deserve to be told. And they need to be told by the people who experience them first-hand.

For the first installment of a (non-regular) “iPad in Real Life” series, I asked Erik Hess to show me how the iPad has improved his flying experience in the cockpit.

Erik Hess spent 13 years as a pilot in the US Navy flying F–14B Tomcats and F/A–18E/F Super Hornets from aircraft carriers. He’s now a full-time designer and partner at high90 and continues to fly the F–5N Tiger II as an adversary pilot in the US Navy Reserve. He posts occasionally at his blog The Mindful Bit and you can find him on Twitter.

I asked Erik to share his experience in using the iPad as a flight-aiding tool in the cockpit. The result is a detailed account written by Erik himself covering a wide range of aspects from software used and replacing paper charts to portability and the importance of the Retina display. Perfect for what I was looking for, I left Erik’s thoughts mostly untouched because I believe, for this series, I should let these voices speak for themselves. Aside from minor editing, I chose to offer Erik’s own story, rather than my summary of it.

Editor’s note: Due to the length of Erik’s story, paragraphs written by him start with “Erik” in bold and are followed by multiple paragraphs with quotes at the start and end of the block.

I asked Erik to tell me a bit more about his background in the aviation.

Erik: “I fly the F–5N Tiger II as a Reservist for the US Navy. Before this I was on active duty for about 13 years, where I flew F–14 Tomcats and F/A–18 Super Hornets off aircraft carriers. The Tiger is a small one or two-seat fighter built in the 1960s and 1970s. The Navy uses them to simulate various threat aircraft in order to prepare fleet pilots for upcoming deployments. Its small claim to fame was as a stand-in for the fictitious “MiG–28” in the 1986 movie Top Gun.”

For context, here’s what a two-seat F–5F looks like:

Why the iPad?

As I started my research into interesting use cases for the iPad, the cockpit wasn’t exactly the first possible answer that came to my mind. But I should have known better: it’s been widely reported on a variety of occasions that pilots have been increasingly replacing heavy, bulky paper charts with smaller, more durable, and definitely more versatile and intelligent iPads. There must be a difference, I thought, between flying consumer lines and smaller cockpits such as the one of the F–5N.

Erik: “The cockpit of a fighter is a small and specialized place. Imagine the smallest sports car you’ve ever seen. Rip off the roof and replace it with glass, then chop out the passenger seat and whatever tiny back seat the manufacturer included as a tease. Now replace everything that’s soft and comfortable (including the seat) with metal and a few bits of hard plastic. Replace your seat cushions with a couple of cheap ones ripped off an outdoor furniture set at your local home store, and triple the complexity of your seat belt.”

Erik: “Just like your car, that instrument panel will stay practically unchanged after it leaves the factory floor. In the case of my F–5, that was about forty years ago. For perspective, when my airplane was built, cars looked like this; the most popular telecommunication device looked like this. With the exception of some small upgrades, the cockpit design is about fifteen years older than that. Clearly, vehicle and communication technology has advanced substantially in the last forty years.

The Navy chose the F–5 for its low cost and high maintainability, so to keep costs to a minimum its communication and navigation technology remains rooted in the past. While it’s easy to get used to high-speed wireless Internet wherever you go on the ground, in the air the only way I can get information about the world around me is through my own eyes or through the two onboard radios. This can make it difficult to get up-to-the minute weather information.

We have a somewhat limited radar that can see rainstorms if they’re heavy enough, but the returns aren’t overlaid on any map data. The same goes for the GPS that was added a few years ago. I can steer to a pre-programmed waypoint, but only if someone loaded it into the hundred-or-so slots available to the system. There’s no internal map to give a sense of where you are or how you’re going to get where you’re going.

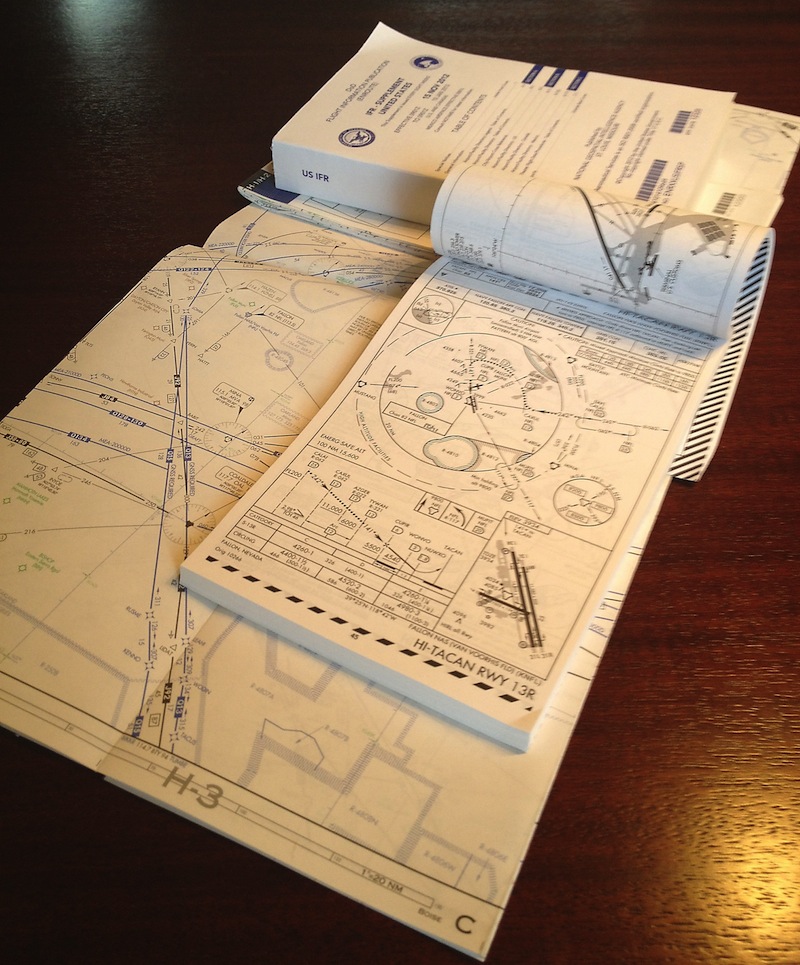

Instead, we navigate the old-fashioned way:

While paper charts are great (they’re cheap and don’t need batteries) there are a few limitations. For a cross-country flight, you often have to carry a half-dozen publications or more. This can be difficult with the limited space available in the cockpit.

Additionally, our jet doesn’t have an autopilot, so that means my hands are usually busy keeping the airplane moving in the right direction. It’s cumbersome and time consuming to try to fold a large, unwieldy chart or find the one approach plate you need in a hundred-page book when you cover a mile every eight seconds.

Luckily, there are now other options”.

Pre-Flight Planning

As you can imagine, the strength of the iPad is not the hardware itself – what really improved navigation in the cockpit is the software.

Erik: “There are two tasks all pilots perform prior to a flight, regardless of whether they’re about to strap into a Cessna or a Super Hornet: planning their route of flight and checking the weather along that route.

Our local training missions use a fairly consistent piece of sky called the Fallon Range Training Complex. The local areas are already plugged into our aircraft’s internal navigation system, so I rarely need to spend much time on planning for flights near our home.

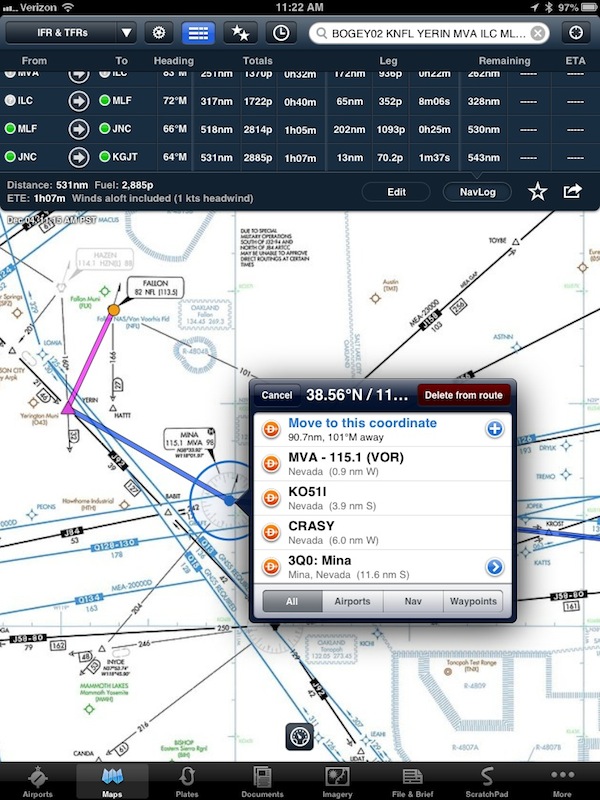

Occasionally we’ll venture farther afield, and then preflight route planning is essential. My weapon of choice for this task is ForeFlight Mobile.

While ForeFlight might seem expensive ($74.99 per year or $149.99 per year with geo-registered approach plates and taxi diagrams) that price is highly competitive in the aviation market. It offers direct entry or drag-and-drop route planning, along with a just-right level of fuel burn calculations that gives accurate results with a minimum amount of fussiness.

While I can easily file a flight plan with Air Traffic Control at our home field, when we’re on a cross-country ForeFlight lets you file right from the app. It’s faster and easier than calling the free 1–800-WX-BRIEF service, especially when I’ve already entered all the relevant information into the app.

The second major task in preflight planning is making sure the weather is good enough for the trip. Aviation weather reports are highly detailed, and come in a specialized, highly encoded form.

Even a simple forecast like “Partly cloudy with light southeast winds” gets a lot more detail in aviation-speak:

KNFL 0418/0420 13005KT SCT030 FEW200

For quick weather reports, I use AeroWeather Pro by Pascal Dreer on my iPhone.

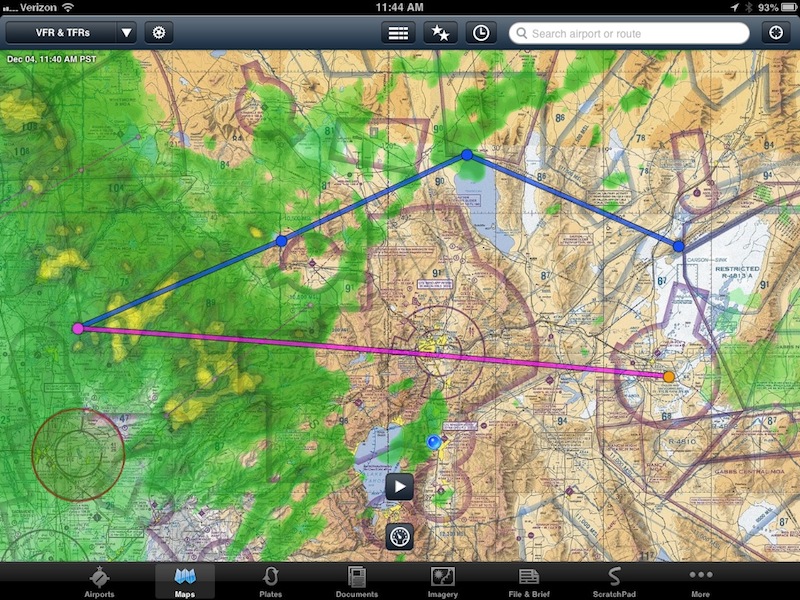

Sometimes having a weather radar overlaid on your route of flight can be extremely helpful, especially out here in the mountains of western Nevada. For that I return to ForeFlight:

What’s especially helpful is that you can overlay the weather data on the visual or instrument charts of your choice. ForeFlight also offers taxiway diagrams, frequencies, airfield services and Notices to Airmen (NOTAMS).

In addition to pre-flight planning and weather, I use GoodReader linked to my Dropbox account to keep track of references like inflight guides, flight manuals, and instructions, all of which are usually available as PDF documents”.

In-Cockpit Assistance

While I’m all for getting the right apps to do a very specific job, Erik told me that “once airborne, minimizing space and distractions is of prime importance”. After all, he’s still flying an aircraft, and he can’t be looking at apps all the time.

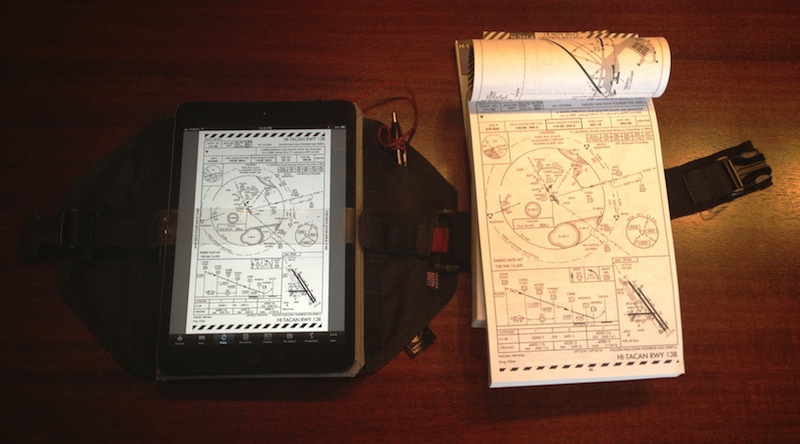

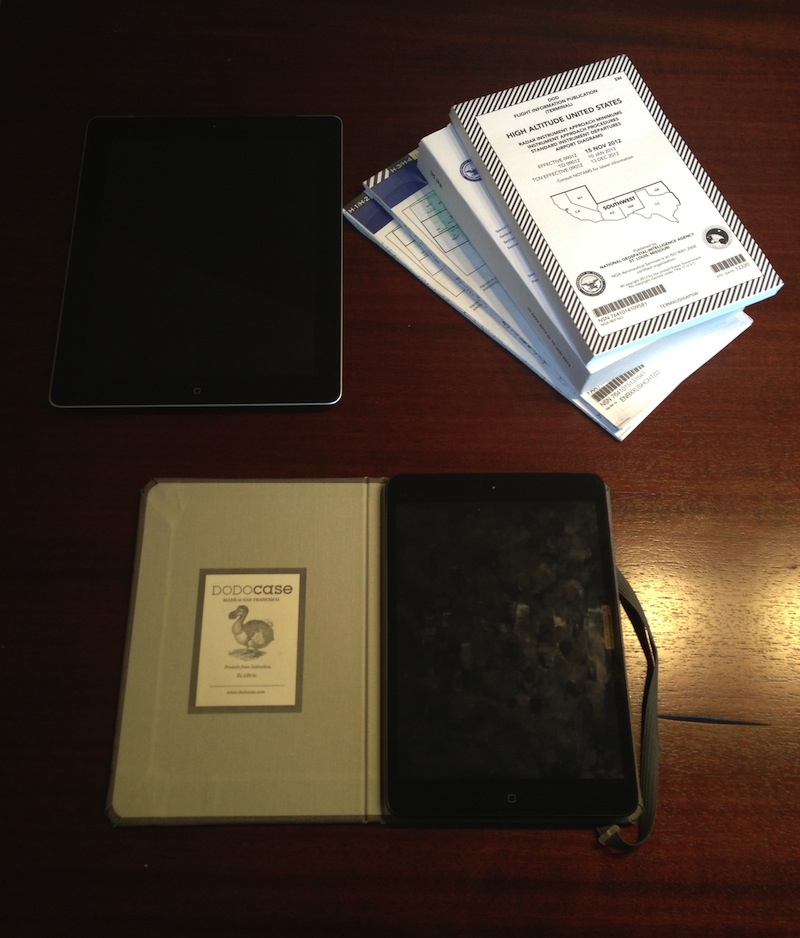

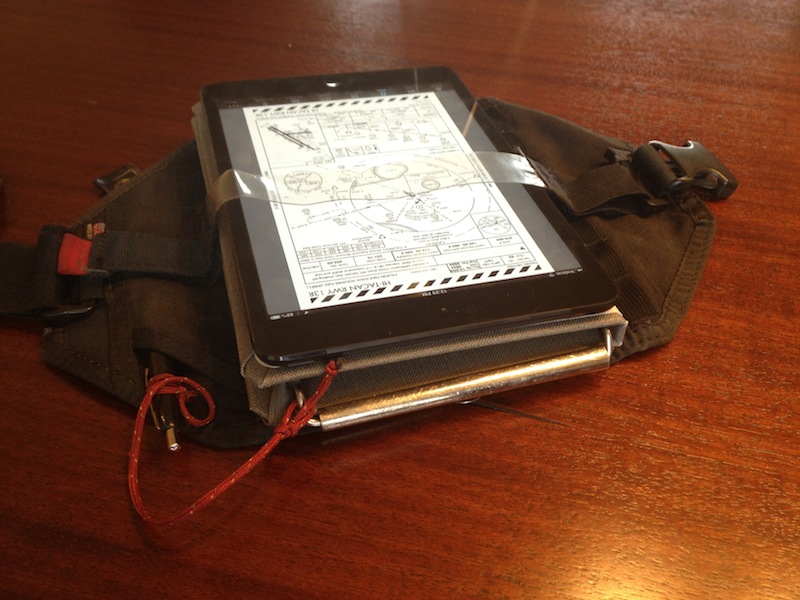

Erik: “At first I used my 10“ iPad 3 attached to the Sporty’s iPad Kneeboard. While it was surprisingly useable considering its size, the 10” iPad is far too large and unstable to be useful for tactical flying.

Luckily, Apple came to the rescue with the iPad mini. I purchased a 32GB black iPad mini with Verizon LTE just about as soon as I could, and it’s a much better fit in the cramped confines of the Tiger’s cockpit.

It fits perfectly on the minimalist Hendricks 9G+ Kneeboard I bought from Wings Aviation Supplies in Pensacola, FL, long ago as a flight student. Long the standard kneeboard among Navy fighter pilots, the 9G’s clip fastens securely to the top cover of my DODOcase HARDcover Solid for iPad mini. The clear plastic “negative-G” strap gives a little extra peace-of-mind and poses no obstacle to the capacitive touchscreen.

As you can see, it’s just about exactly the same size as our standard approach plates, but a whole lot easier to use. I don’t need a light to illuminate it at night, and I never have to unclip it to flip a page. Rather than just a few states’ worth of information, I’ve got all publications for all states at my fingertips with just a swipe, which cuts down on the amount of paper I have to lug with me in the tiny F–5 cockpit.

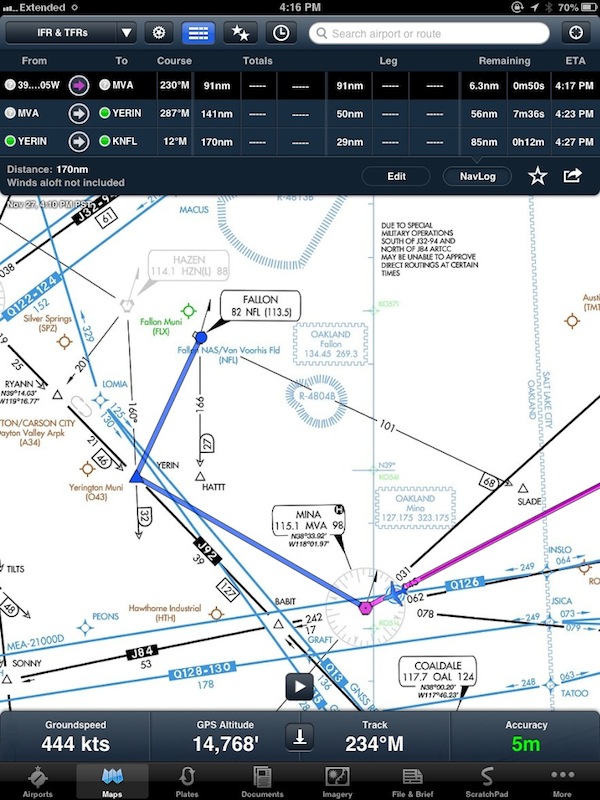

ForeFlight works great as an inflight reference tool, with live updating of aircraft position while enroute. I had no trouble getting a GPS fix, but that might be because I’ve only got a plexiglass canopy between myself and the satellites.

The enroute view is helpful but is more of a reference than a turn-by-turn navigation system, with minimal course guidance beyond speed, altitude and track.

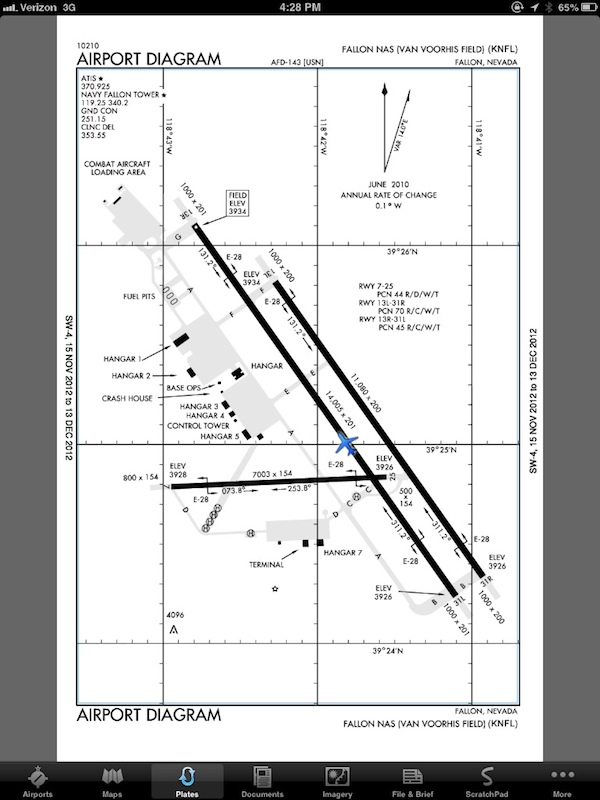

The lower-priced ForeFlight account gives enroute navigation only. If you upgrade to the Pro account, you get geo-referenced approach plates and airport diagrams. The latter can be very helpful when trying to find your parking place at an unfamiliar airfield”.

Editor’s note: The digital charts are not classified material and they are products of the US Federal Aviation Administration. They’re available for download here; ForeFlight collects them, keeps them up to date, and provides several other features on top of them.

Some Caveats

The all-digital setup isn’t perfect though, as Erik told me me “there are still some significant limitations” with using the iPad both before and during a flight.

Erik: “As I discussed earlier, the 10” iPad is just too large to comfortably use in a fighter cockpit. The Retina display is very helpful (especially with detailed diagrams and charts) so pilots with larger flight decks may find the larger screen a definite plus. The battery on the iPad and iPad mini is excellent, but heavy use of the screen and GPS will still take its toll. For a few hours of flying that’s not a big deal, but if I’m flying a multi-leg route I’ll disable the cellular radio while cruising, then turn it back on as part of my pre-descent routine. It’s rare that you get signal at altitude anyway.

Unfortunately, the GPS is part of the cellular radio so disabling it will cause you to lose location data. Since I use ForeFlight as a reference and not for primary navigation this isn’t a big deal for me; you can always turn it back on in a few seconds if required in an emergency.

The screen reflections are at best distracting and at worst make the iPad nearly unuseable. This seems to be even worse on the mini, since I’ve found it picks up fingerprints much more easily than my iPad 3. iOS devices have never been good in bright sunlight, and that’s no different in the cockpit. Still, I’ve used my iPad several times on clear-sky flights and it’s never been worse than an inconvenience. There are many sharp metal objects in a fighter cockpit, and I’m more than a little concerned about scratching or breaking the iPad’s screen. I’ve had no issues yet, but worrying about breakage has been more than a little distracting at times.

Finally, due to regulations I’ve still got to carry all the charts and approach plates for my flight. The iPad can’t officially replace any of these things yet, and besides it’s still a good idea to keep them around in case of failure. Other than making my bag a little heavier this hasn’t been a major problem for me”.

iPad Air

At the end of our discussion, I asked Erik to sum up his thoughts on the iPad. Has the device proven to be a concretely better experience than old maps and charts?

“The iPad makes a great inflight aid, and if it works in a fighter cockpit you can bet it would be even better in the more spacious and comfortable cabins of private and commercial aircraft”. As for the software, Erik said that, in his opinion, “there are already several excellent flying apps out there and they get better all the time”.

When I ask him about the future, Erik doesn’t have any doubts: the iPad is going to stay in the cockpit. With one improvement, though: “I’m working on a more permanent kneeboard solution for my iPad mini, but it’s going to be flying with me for the foreseeable future”.