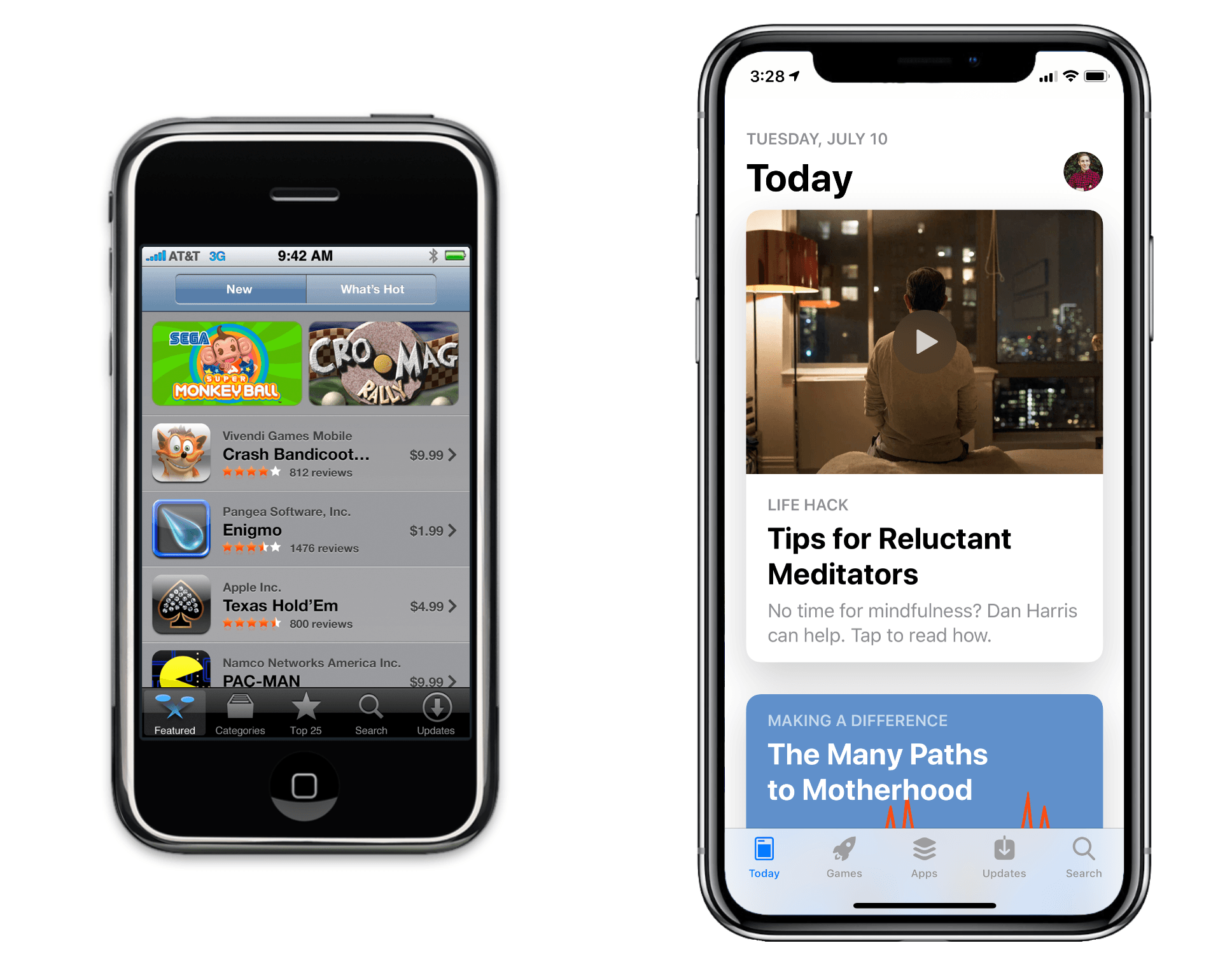

“There’s an app for that” may have been coined as a marketing term in 2009, but in 2018 the phrase is indisputable. With over 2 million apps on the App Store, there is seldom a niche unexplored, and few obvious utilities not rapaciously overindulged. The App Store is a worldwide phenomenon, an enormous entity providing instant access to a treasure trove of software for hundreds of millions of people. Things have come a long way in a decade.

Ten years ago today, the App Store launched with 552 apps, available only on the original iPhone, iPod Touch, and the iPhone 3G (which shipped the day after). The developers of those apps overcame a fascinating set of challenges to secure front row seats in one of the greatest software advents in history. Many of these apps were built into sustainable businesses, and continue in active development today. Even those that didn’t make it are still testaments to their time, effortlessly invoking nostalgia in users who participated in that era.

The early days of the App Store were a journey into the unknown for Apple, third-party developers, and users alike. The economics of the store were entirely unrealized – nobody knew which app ideas would work or how much they could charge for an app. Apple’s processes for approving apps were primitive, their developer documentation was fallow, and they still thought it a good idea to make developers sign a non-disclosure agreement in order to access the SDK (software development kit). For iPhone users, every new app could completely revolutionize their mobile experience, or it could be another icon they never tapped on again.

Despite this uncertainty, developers pushed forward with their ideas, Apple hustled as many apps through approval as it could, and on July 10, 2008, users exploded enthusiastically onto the scene. Within the first year of the App Store, iPhone and iPod Touch owners had already downloaded over 1.5 billion apps. From the beginning it was clear that the App Store would be an unmitigated success.

Developing for App Store Day One

The months preceding the launch of the App Store were no simple undertaking for interested developers. Apple’s developer program cost $99 to gain access to, and required signing a strict non-disclosure agreement. This NDA prevented developers from discussing the iPhone OS1 SDK publicly, which meant sites like Stack Overflow and other public forums could not be used to pool information about solving common problems. On top of the NDA, Apple’s documentation for developing on the iPhone was not nearly as comprehensive as it has grown in subsequent years.

All of these issues compounded to make the lives of iPhone OS developers much more difficult than they necessarily needed to be. They were forced to waste time recreating solutions to problems others had already solved, and couldn’t easily disperse information about problems they solved themselves. On the other hand, the SDK for iPhone OS 2.0 was minuscule compared to the intimidating breadth of modern iOS SDKs. The problem set was new and obscure, but mastery of it was much more within reach for tenacious developers.

In an upcoming interview for AppStories as part of our App Store 10th anniversary series, David Smith contrasts the rudimentary development environment for early iPhone apps with the modern day equivalent:

The initial version was so limited and so straightforward, which in many ways was great for someone like me coming at it with no experience. I was in many ways on an even playing field with everyone else because I could relatively quickly understand everything, and then that was all of the world that I needed to learn. Whereas now I think of how hard it must be to be a brand new iPhone developer today – the number of SDKs and things that you would have to think about and manage and understand is just mind-boggling.

Smith is the developer of many great iOS apps, including continued support of his day-one app Audiobooks. These days some of his biggest apps are the step counter Pedometer++ and the sleep tracker Sleep++. In 2008, neither of these apps would have even been possible to build, but Apple’s hardware capabilities and software APIs have grown an enormous amount in ten years. The core benefit of this ballooning complexity has been the establishment of countless new categories in the App Store’s now-sprawling marketplace.

Ten Years on the App Store

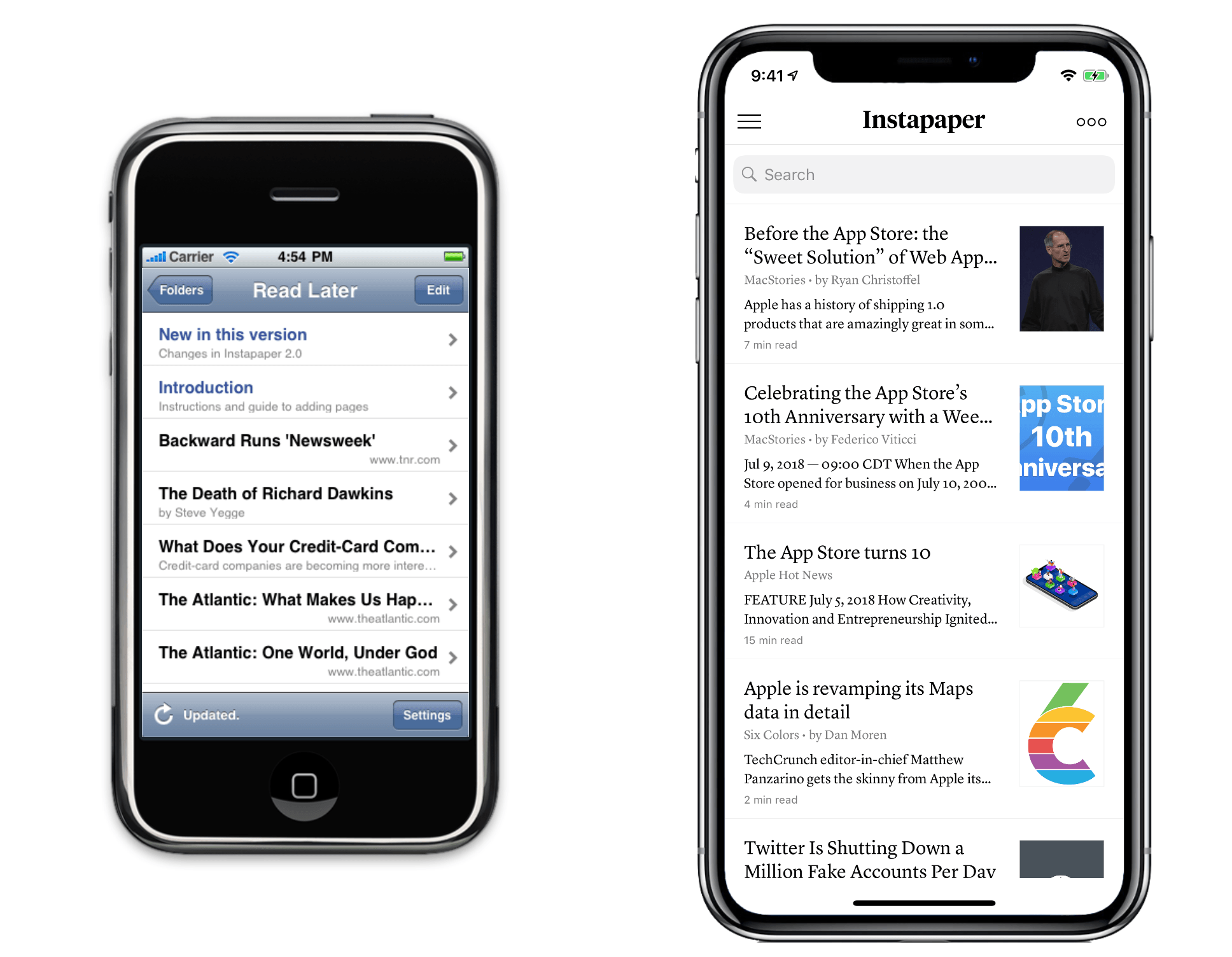

Before the App Store, the idea of a business being “mobile-first” essentially did not exist. The original version of Instapaper, a read-it-later service created by Marco Arment, didn’t even have an option to create an account in its initial iPhone version – the concept that someone would arrive at the app before visiting the website was foreign. Arment, who took part in the same AppStories interview as Smith, described the cultural shift in how web services saw smartphone apps:

The entire mental model of what mattered back then was not “I’m going to launch an app and that’s gonna be the thing.” I was looking at it as “I’m launching the app for my website.”

[…]

Eventually that came to flip itself on its head and I realized the app was “the thing.”

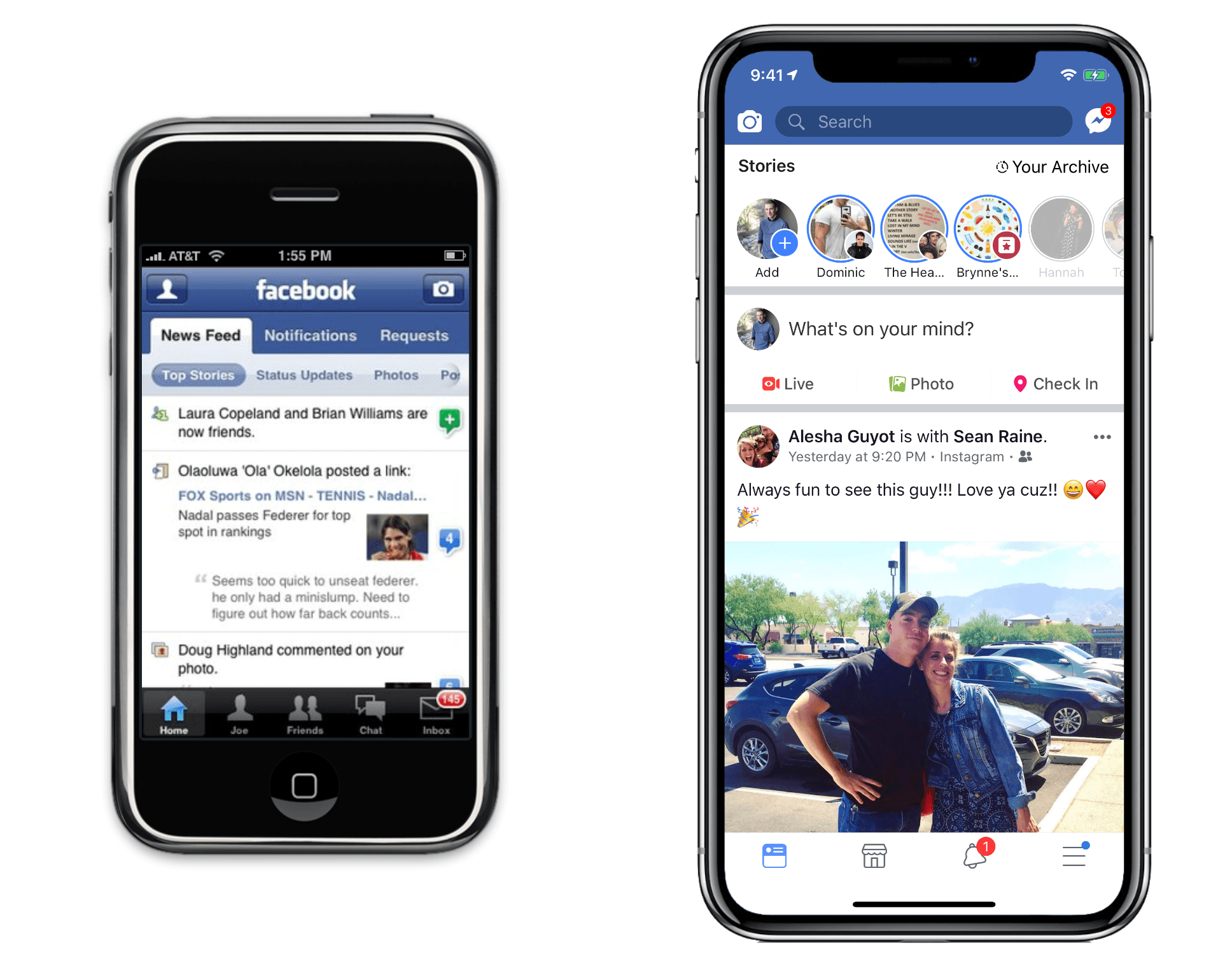

As the iPhone and the App Store grew over the years, every business had to come to this realization at their own pace. Various turning points throughout the last decade triggered the shift for individual companies or developers. Arment pegged the launch of the iPad as the beginning of this transition for his business, which makes sense for an app in which reading is core to the experience. For other companies, such as Facebook, the iPad made almost no waves whatsoever. The company was one of the first 500 apps on the iPhone in 2008, but didn’t get around to making an iPad app until almost two years after the iPad was announced. Even with their mobile offerings though, it would be years before Facebook finally went all-in on the transition to mobile-first.

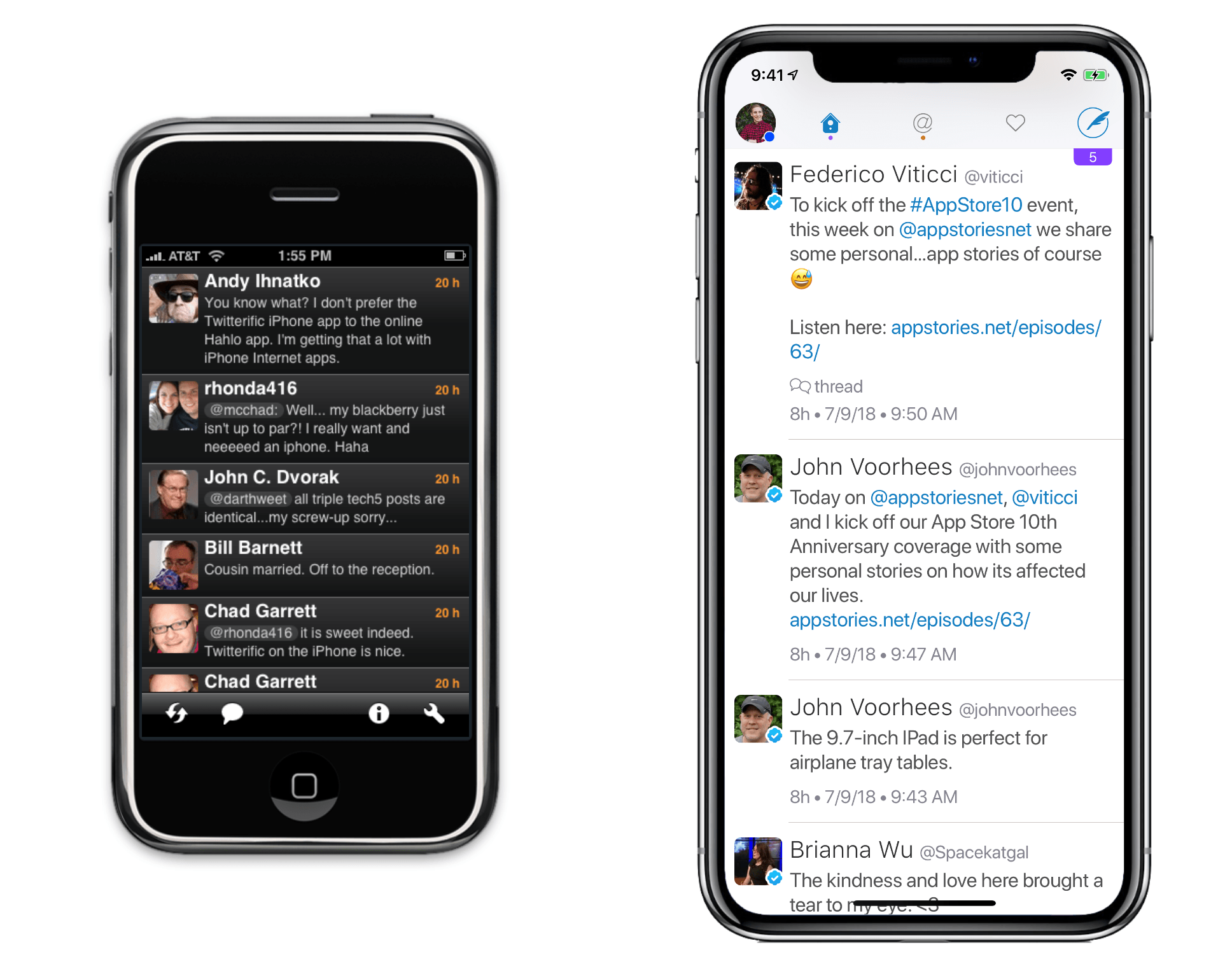

Twitter didn’t seem to catch onto the importance of the App Store at all at first, not even bothering to have a first-party app until they acquired Tweetie years later. This left the door wide open for tenacious independent developers to take charge. Craig Hockenberry, a developer at The Iconfactory, saw immediately that the iPhone was a perfect place for a Twitter client. He had a version of Twitterrific, The Iconfactory’s previously Mac-only Twitter client, running on a jailbroken original iPhone months before the iPhone OS SDK was even announced. We interviewed Craig in today’s App Store Anniversary AppStories episode, and he had some interesting insights on the era:

When the iPhone was announced it was so obvious that [Twitterrific] needed to be on a mobile device. When I did the jailbreak version you could read tweets while you were standing in line at the bank, or you’re waiting for a bus, or you’re at the airport flying up to WWDC.

[…]

It was so obvious that it needed to be on the phone, it just fit. Twitter got its start with SMS messaging – it was kind of a mobile platform from day one. Then it transitioned to the web, that was where it grew up…but it came back to mobile when the iPhone and other smartphones appeared.

Twitterrific made its official iPhone debut on day one of the App Store, where it held a position among the top ten social networking apps for the year. Ten years later, Twitterrific still stands as one of the best Twitter clients for both iOS and macOS. The app has changed significantly over the years, as all apps have. It flattened its interface to make the leap into the post-iOS 7 era, and it added many great new features which were not possible for that original version.

Making it for ten years on the App Store is no easy task, and many of those original 500 apps have not managed to stay afloat. Some of them just didn’t stand the test of time, aging out of their usefulness or novelty. Others could not sustain living wages for their developers, or their developers simply transitioned to different work and left their apps behind. Many of these apps were finally cleared out of the store just last year, when Apple chose to remove all legacy 32-bit apps.

In the face of the innate challenges of maintaining an application for an entire decade, on a platform which was entirely unproven at the time the app was first written, it’s pretty astounding how many of those apps are still actively developed. While the aforementioned Instapaper is no longer managed by Marco Arment, it continues to chug away as one of the premier read-it-later services under its new ownership. The app itself has transformed quite a bit over the years, adjusting to changing interface patterns as any enduring software must.

Facebook has orchestrated an unbelievable decade, growing into one of the biggest technology companies in the world, and collecting over 2 billon monthly active users. Unlike many others, the social network did eventually manage to transition into a mobile-first business. This is a multi-billion dollar company whose main revenue stream comes from advertisements through mobile applications, a category which did not exist until the App Store launched in 2008. Facebook’s app, unsurprisingly, has undergone significant changes in the years since its launch on day one.

One of the most wonderful aspects of the App Store is how it puts apps from massive corporations like Facebook on an even playing field with apps written by individual independent developers or small firms. The store is an open marketplace where any quality app has the potential to take off and become a huge hit. In today’s store, with over 2 million apps participating, the noise of such a vast market can often drown this quality out. In July of 2008 though, it was a massive opportunity for any app to explode.

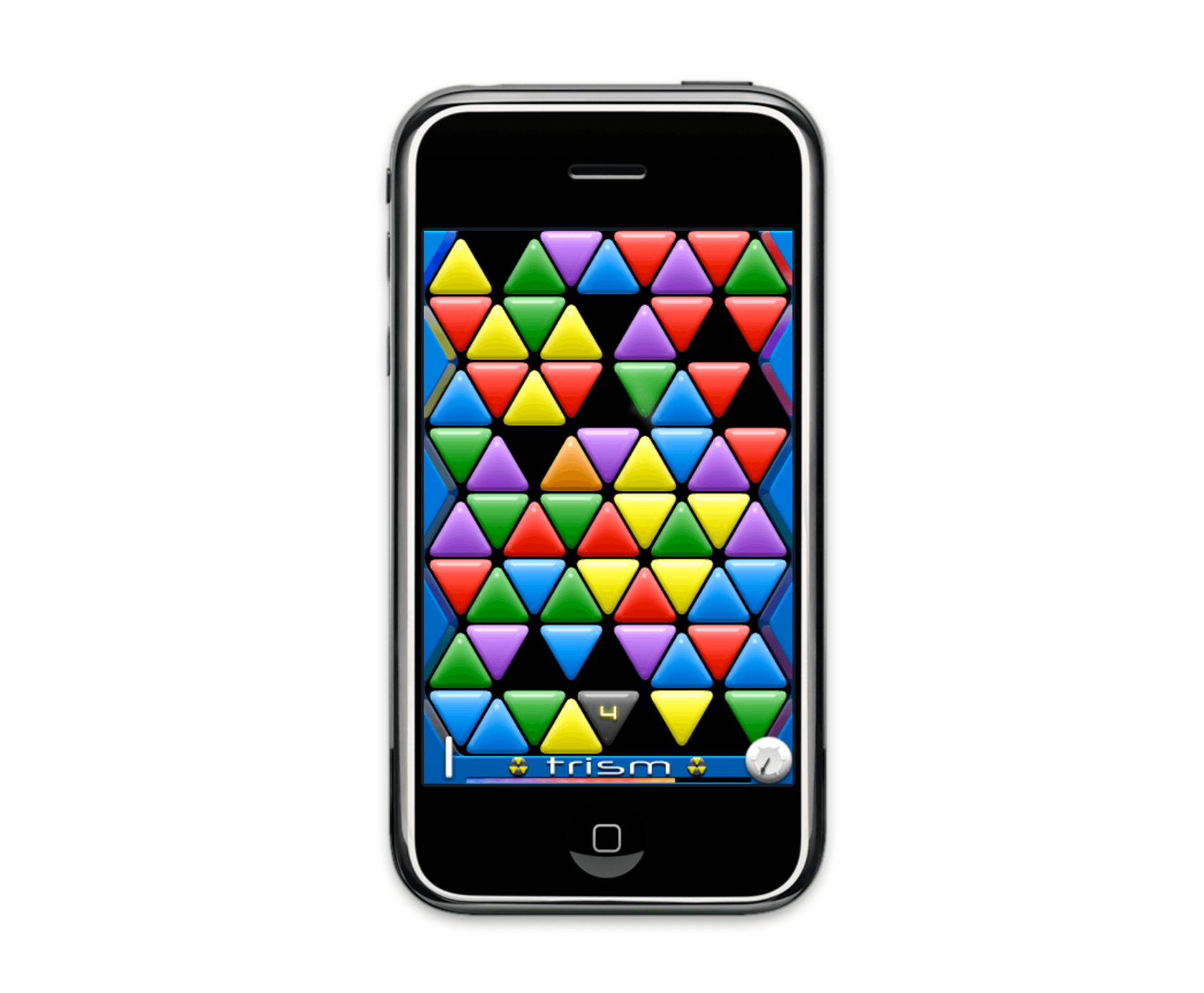

A crowning example of this phenomenon is Trism, a simple puzzle game from independent developer Steve Demeter. As one of the first ever games for iPhone, Trism became an almost overnight success shortly after the launch of the App Store. Demeter made hundreds of thousands of dollars in the first few months, was interviewed on TV, featured in articles and documentaries, and decorated with multiple awards. The story of Trism has been told before, but suffice it to say that the sudden spotlight was not handled well by Demeter. A decade later though, Demeter is back for Trism’s tenth anniversary. Variety reported just last week that Trism 2 was ready to go and set for release. As of just this morning, the long-awaited sequel is out on the App Store.

Throughout the App Store’s ten years have been countless stories of sudden, explosive success. Some, like the frustrating platformer Flappy Bird, have resulted in similar difficult times as Trism for their developers. Others, like Instagram, have led to billion dollar acquisitions. Tales of fame and fortune have ensnared headlines the world over, but flying below the radar of these evanescent stars are tens of thousands of hardworking independent developers building sustainable businesses and making decent livings on the App Store.

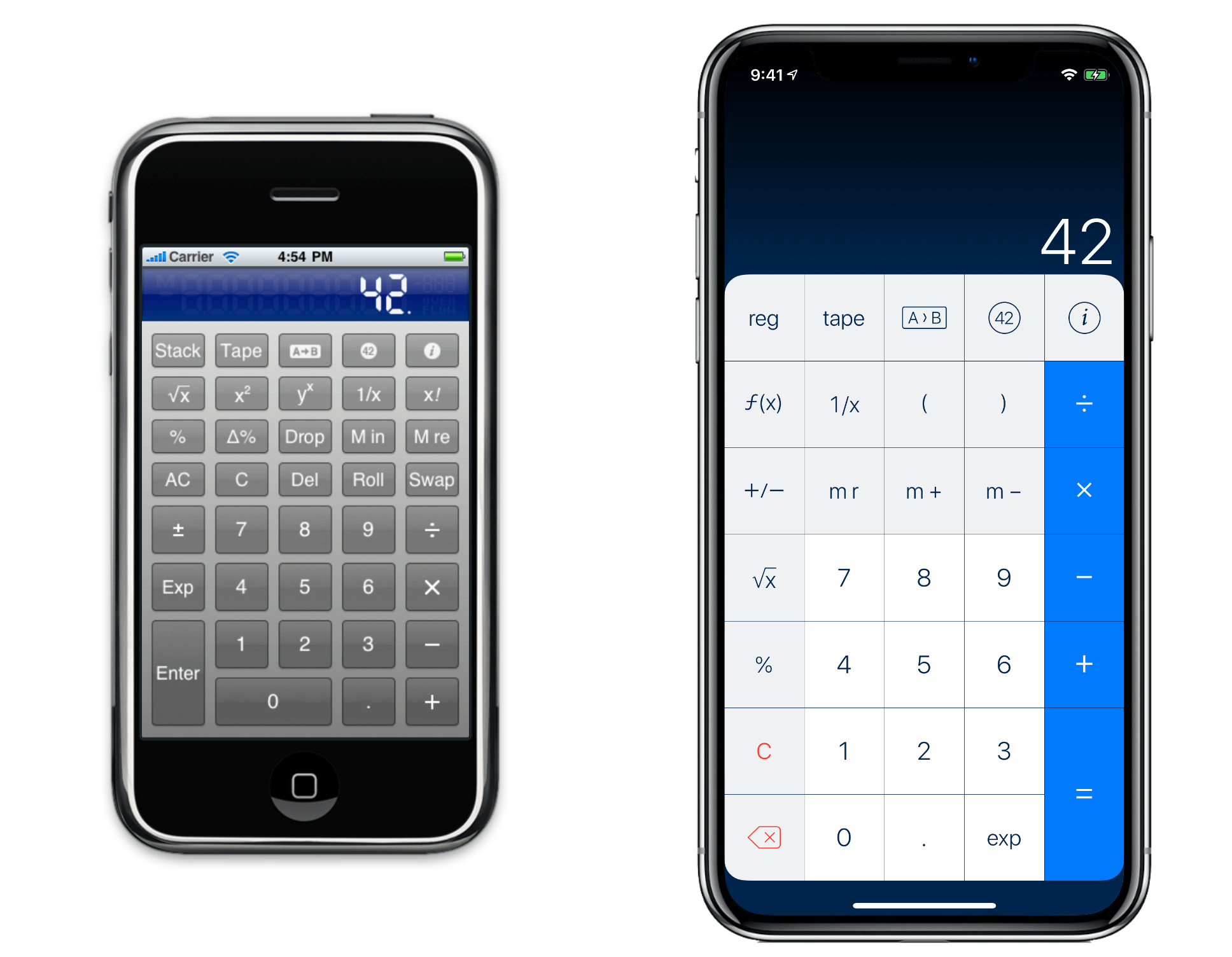

One of the best stories of an indie dev is that of James Thomson, who developed a simple calculator app for the iPhone and launched it on day one of the App Store for $10. Ten years later, the excellent PCalc is still going strong. Thomson has stood stoically behind that $10 paid-up-front price point, resisting the race-to-the-bottom mentality that has overtaken much of the App Store’s pricing models. Over the years he has never been afraid to expand PCalc to new platforms, or to try out new features. Today the calculator app can be found on iPhone, iPad, Mac, Apple Watch, and even Apple TV. It works with iPad Split View multitasking, supports drag and drop, sports a great widget, and offers a variety of custom icon color schemes. Driven by his interest in Apple’s recent ARKit framework for building augmented reality apps, Thomson even shipped an AR playground and racing game hidden in PCalc’s About screen.

Thomson joined Federico and John on the same AppStories episode as Hockenberry. During the interview he touched on his decade of devotion to the complicated execution of a simple app idea:

The whole point of PCalc on the phone was that it was a small enough app that I could do a quick example of building an iPhone app – learn how to use the stuff – and then I would move on to do the “real app” that I was going to write for the iPhone. But you know, I never actually got past the first app.

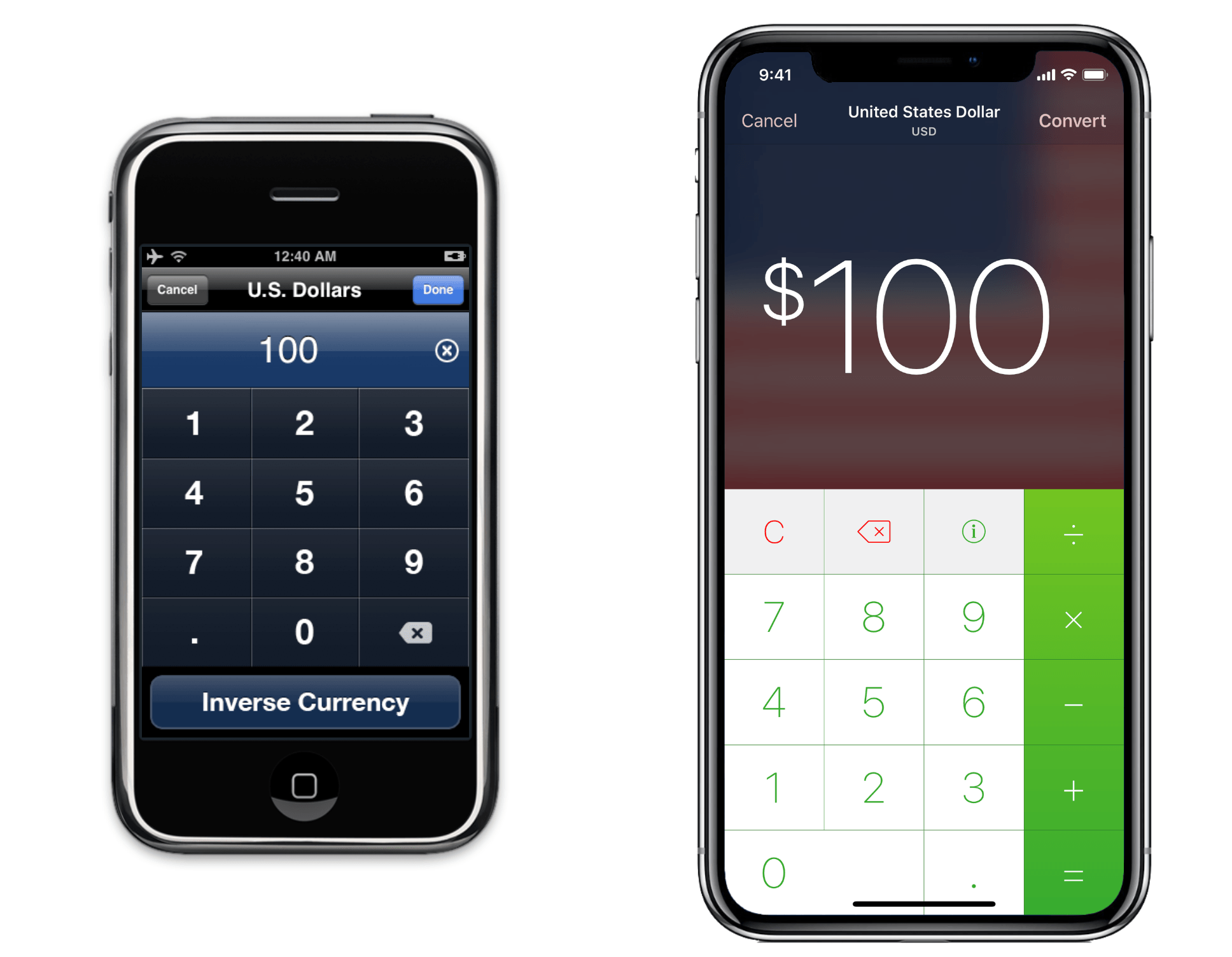

Currency is another example of an iOS app which boasts a decade of independent work. Developer Jeffrey Grossman launched the currency converter on the first day of the App Store as a free download. Over time he built his business by adding a single banner ad at the top of Currency, with an in-app purchase to remove the ad once that option became available. Grossman has worked hard to keep Currency a first-class iOS citizen, updating it consistently with new core platform features as Apple has released them. I asked Grossman what some of the biggest changes to his app have been over the last decade, and he had this to say:

The largest improvements to Currency in the past 10 years have come from the platform changes that Apple has provided, such as multitasking, iPad, iCloud, Extensions, and Apple Watch. Someone can run Safari and Currency in Split View on iPad, and drag a numerical value from Safari and drop it into Currency to quickly perform a conversion. That value automatically syncs to their iPhone, Today widget, and Apple Watch. It’s also always been important to me for the app to work completely offline, so implementing the Background App Refresh APIs means that the app always keeps the exchange rates up to date and can be used in the future if the device doesn’t have a network connection (such as if someone is traveling internationally and has turned off data roaming). Obviously none of that was possible with the original iPhone and first version of Currency.

Today’s App Store

As Grossman’s comments make clear, the complexity of modern day iOS apps has grown significantly since the launch of the App Store. Almost all of the biggest hurdles for developers in 2008 have been overcome: developer tools and documentation are vastly improved, the NDA was long ago abolished, distributing apps for testing is far simpler, and App Store approval is measured in days instead of weeks. Despite this, the expanding complexity of building iOS apps means that the problem set has simply shifted rather than being eliminated entirely. Just like in the old days though, determined developers who can overcome these challenges and release great products are still more than capable of building a sustainable business on the App Store.

With a decade under its belt, the App Store already has an impressive legacy. Apple’s software marketplace has changed the way the world works, impacting millions of lives and providing a living for tens of thousands of developers. Much has changed in ten years, but Apple’s dedication to democratizing secure, powerful software for all of its customers has not. Today’s App Store may be a different place from that tiny, unproven ecosystem of 2008, but it has remained true to its core values, and achieved its goals spectacularly.

- Apple’s touch operating system was known as “iPhone OS” for its first three versions, only changing to “iOS” with the debut of iOS 4, shortly after the launch of the iPad in 2010. ↩︎