Everyone acknowledges the societal and technological effects the iPhone has had on the world. In late 2007, Time named the original model its “invention of the year,” and rightfully proclaimed it “the phone that changed phones forever.” Eleven years on, it is genuinely difficult to remember the world before the iPhone existed. Whatever your platform allegiance, there can be no disputing that the first iPhone pioneered the notion that everyone should carry a touchscreen supercomputer with them wherever they go. In hindsight, Steve Jobs wasn’t exaggerating when he boasted Apple would reinvent the phone.

Yet for everything the iPhone has meant to smartphones and to the world, there is a segment of users for which the iPhone has been truly revolutionary: disabled people. For many people with disabilities, myself included, the iPhone was the first accessible smartphone. The device’s multitouch user interface and large (for the time) display represented a total break from the smartphone conventions of the day. An unheralded ramification of this was how accessible these features made the iPhone. For example, the soft keyboard allowed users to compose text messages and emails without struggling with the T9 keyboards that were commonplace at the time. Likewise, the iPhone’s 3.5-inch display was considered large for the day, which made seeing content markedly easier than on the postage stamp-sized displays that dominated cell phones then. It’s a testament to the original iPhone’s greatness that its fundamental components were so solid that they redefined accessible computing, all without being “accessible” in the traditional sense. Its impact is put into greater perspective when you consider the first two versions of iOS (née iPhone OS) didn’t contain discrete accessibility features. The first bunch, VoiceOver, Zoom, and Mono Audio debuted in 2009 with the 3GS.

Enter the App Store

You can argue a case that the addition of the App Store in 2008 was more of a watershed moment than the original iPhone because of the way it expanded the phone’s capabilities. The original phone was undoubtedly magical, but the day Apple unveiled the iPhone SDK and announced the App Store was the true game-changing moment for the iPhone. It laid the foundation for the platform on which we all - users and developers alike - stand upon today. Apple created the iPhone, but it was really the developer ecosystem that shaped it into the phenomenon it eventually became.

Just as the App Store made existence possible for Twitter clients to text editors to games to fart apps and more, so too did it promise life for accessibility-centric apps designed to help the disabled. One such company is Amsterdam-based AssistiveWare, makers of the communication app Proloquo2go and the educational keyboard Keedogo, among others. AssistiveWare was developing Mac apps as far back as 2002, and has been a mainstay of the iOS App Store for years. “It is part of our DNA to consider accessibility,” founder and CEO David Niemeijer said via email.

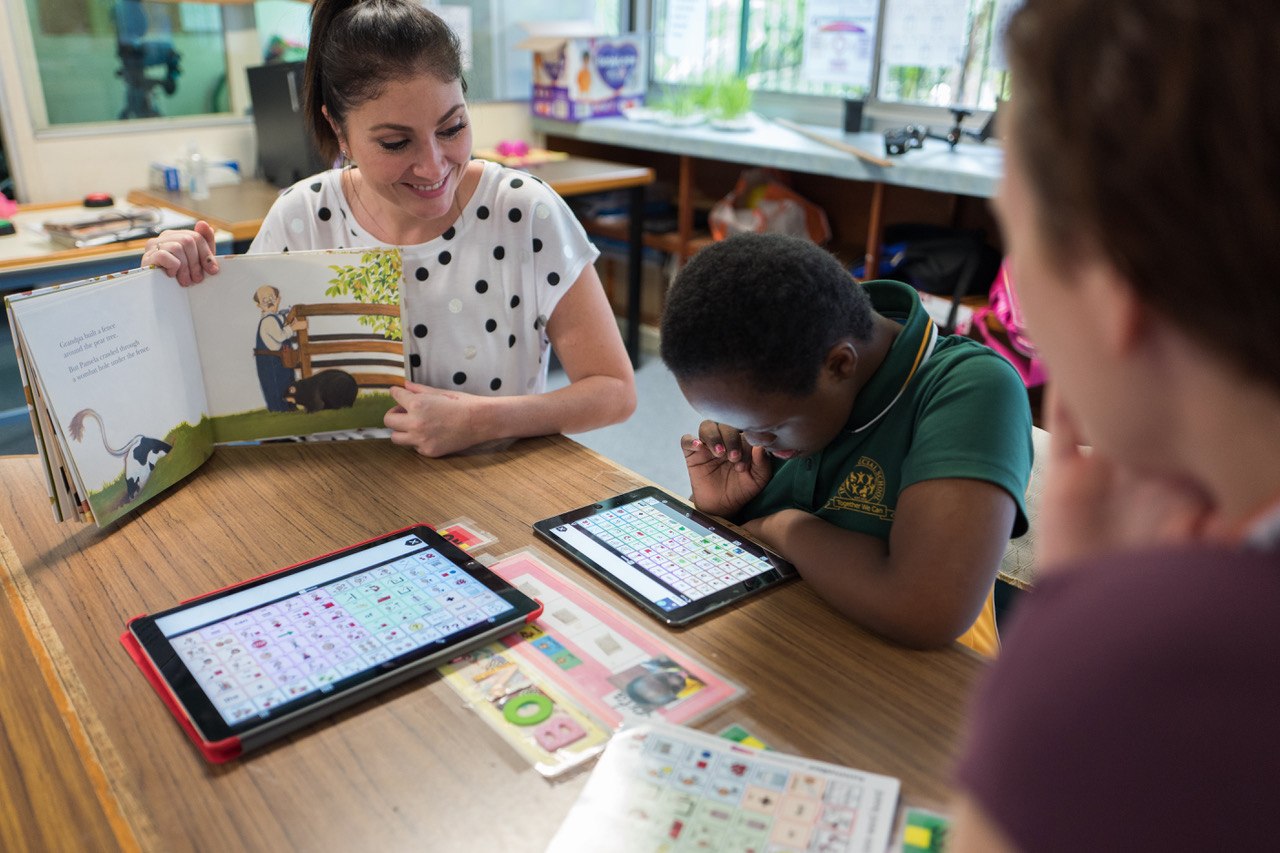

AssistiveWare is a respected name in the Apple accessibility community, akin to how Tapbots, Panic, and The Omni Group are household names in the broader indie developer circle. Their bread and butter app is Proloquo2go, a professional-grade (priced at $249.99) communication board app that is widely used by speech and language pathologists in schools and clinical settings. It is a popular tool with autistic people and others who have limited expressive language or are non-verbal. According to Niemeijer, Proloquo2go is “the leading AAC app for iOS” and has been downloaded more than 200,000 times worldwide.

The App Store is what made Proloquo2go possible. Instead of relying on analog communication boards or dedicated communication board devices, as has been done for decades, the App Store allowed AssistiveWare to deliver what Niemeijer calls “the first complete AAC product for a mainstream mobile device” to speech and language professionals and to families. Proloquo2go did for communication boards what Tweetie did for Twitter clients.

Niemeijer recently published an article on Medium in which he told Proloquo2go’s origin story and discussed how the opening of the App Store led to what he calls the “democratization of access to communication devices.” He details how the launch of the App Store was a seminal moment for AAC users because speech and language therapists and families no longer needed authorized funding for expensive AAC hardware. This happened despite the fact the initial response to Proloquo2go was tepid. Many people, Niemeijer wrote, were concerned the app would “erode the market” for dedicated communication devices. When Proloquo2go launched in 2009, health insurers and speech professionals weren’t phased by the new software at first; it took some time before the new tech was really embraced. It wasn’t until the iPad debuted the next year when Niemeijer says Proloquo2go adoption “skyrocketed.” This was due to the realization there was, for the first time, a fully-fledged AAC solution available on a mass market product.

After AssistiveWare brought Proloquo2go to market, other companies (including manufacturers of dedicated AAC devices) brought their own software to the App Store. Saltillo was the first such company in 2011. Because of this, Niemeijer wrote that the rush of communication board apps in the App Store “liberated” speech professionals, AAC users, and families; there is more opportunity for them because of the store’s model. An iPad was substantially less costly than many dedicated AAC devices.

As Dave Hershberger, CEO at PRC, said to Niemeijer: “iPod touch and iPhone were a big step forward in technology, but maybe more importantly, the App Store changed the world in how software was distributed.”

Of course, Proloquo2go is but one example. The App Store is filled with other accessibility-focused apps, ranging from ones that help you learn American Sign Language to ones that help teachers in special education classrooms create and track IEP goals. Obviously, accessibility-first apps aren’t exclusive to disabled people. Their relevance extends to special education professionals and to loved ones of people with disabilities.

Good Design Is Accessible Design

AssistiveWare (and other similar shops) run their business by making software expressly for accessibility purposes, and as such, they’re attuned to the sensibilities (and APIs) needed to ensure their apps are usable. For Niemeijer and his team, prioritizing accessible design is part and parcel of an app’s development. “Accessibility plays a central part in our design process,” Niemeijer said. “We always consider how we can make sure our products and features are accessible to all of our users.”

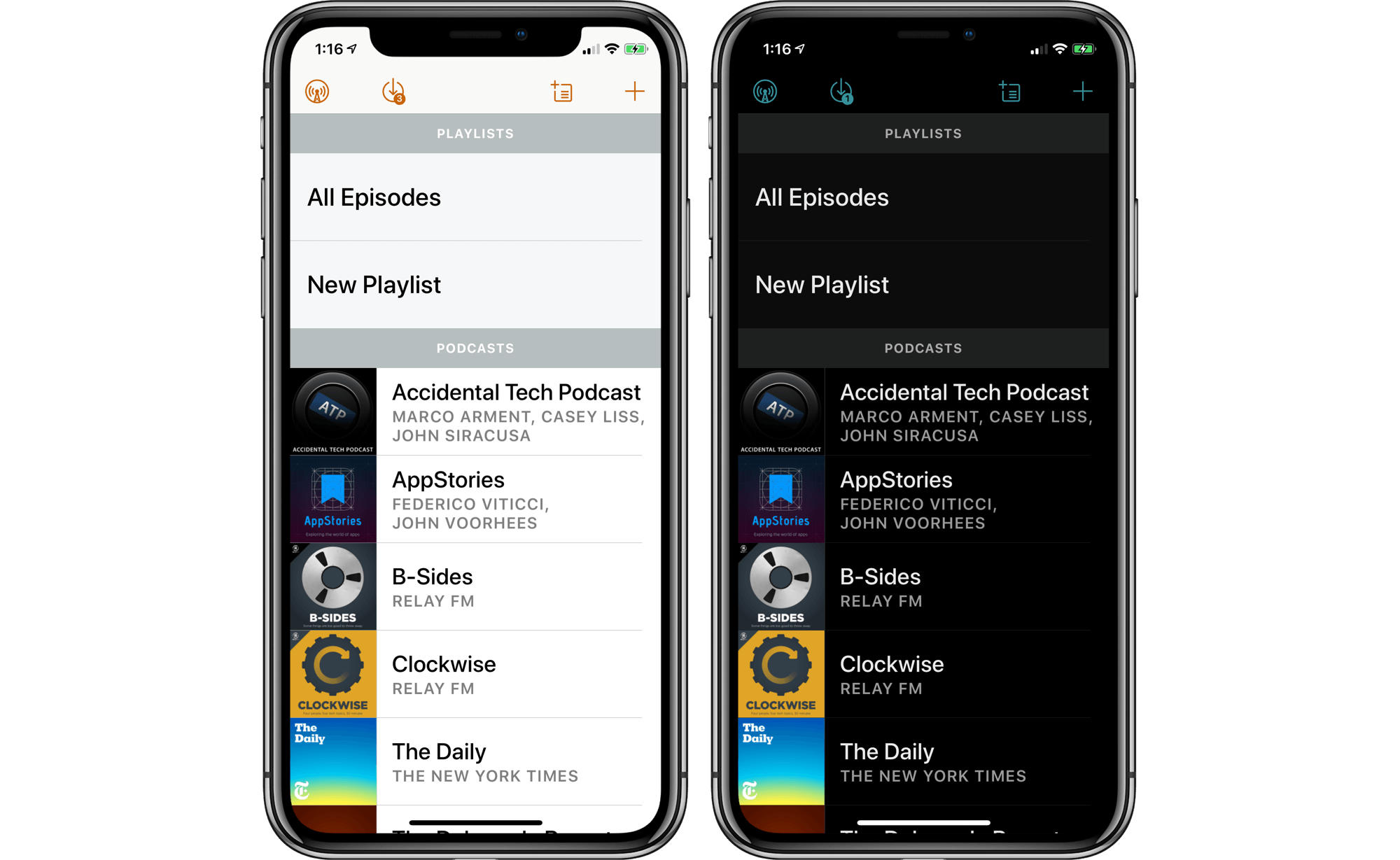

There are, however, numerous developers of more mainstream, general purpose apps that also take great care to ensure their apps are usable by people of all abilities. A prime example is Marco Arment’s highly popular iOS podcast player, Overcast.

Arment has long been an ally of the disabled community, always keen to make sure his apps are usable by the widest possible audience. In a blog post written in 2014, Arment even promoted the idea that Apple’s App Review team test for accessibility.

“Making my app usable by as many people as possible is both good design and good business, and I see accessibility as part of that,” Arment said in an email interview. “Almost everyone will benefit from an accessibility feature at some point, so ensuring my app’s accessibility is just as important as other design requirements and standards for acceptable functionality.”

Overcast is a model citizen, accessibility-wise. It plays nice with Apple’s VoiceOver screen reader, and the app’s user interface is generally visually friendly to people with low vision. Overcast supports Dynamic Type, and the dark modes (particularly the “black” setting on iPhone X) are excellent for users who need higher contrast in order to see their device.

Arment told me he considers accessibility “a peer to other aspects of my design and structure, such as the colors I choose or how interfaces are laid out.” But getting there was a learning experience for him. “I first learned about accessibility with Instapaper back in the early days of the App Store, mostly from feedback by people who couldn’t use it because of shortcomings of my design or implementation,” he said. “When I looked into what it would take to support the accessibility APIs better, I was so embarrassed at how easy it was – I really had no excuse, except ignorance, for not supporting it earlier.”

Arment’s sentiment echoes similar views expressed to me during WWDC. As I reported for TechCrunch, several student scholarship winners I spoke with said they were eager to learn about what accessibility is, how it works, and how to best support it in their apps. Like Arment, their belief is that it’s not only the right thing to do by everyone, but it makes smart business sense too.

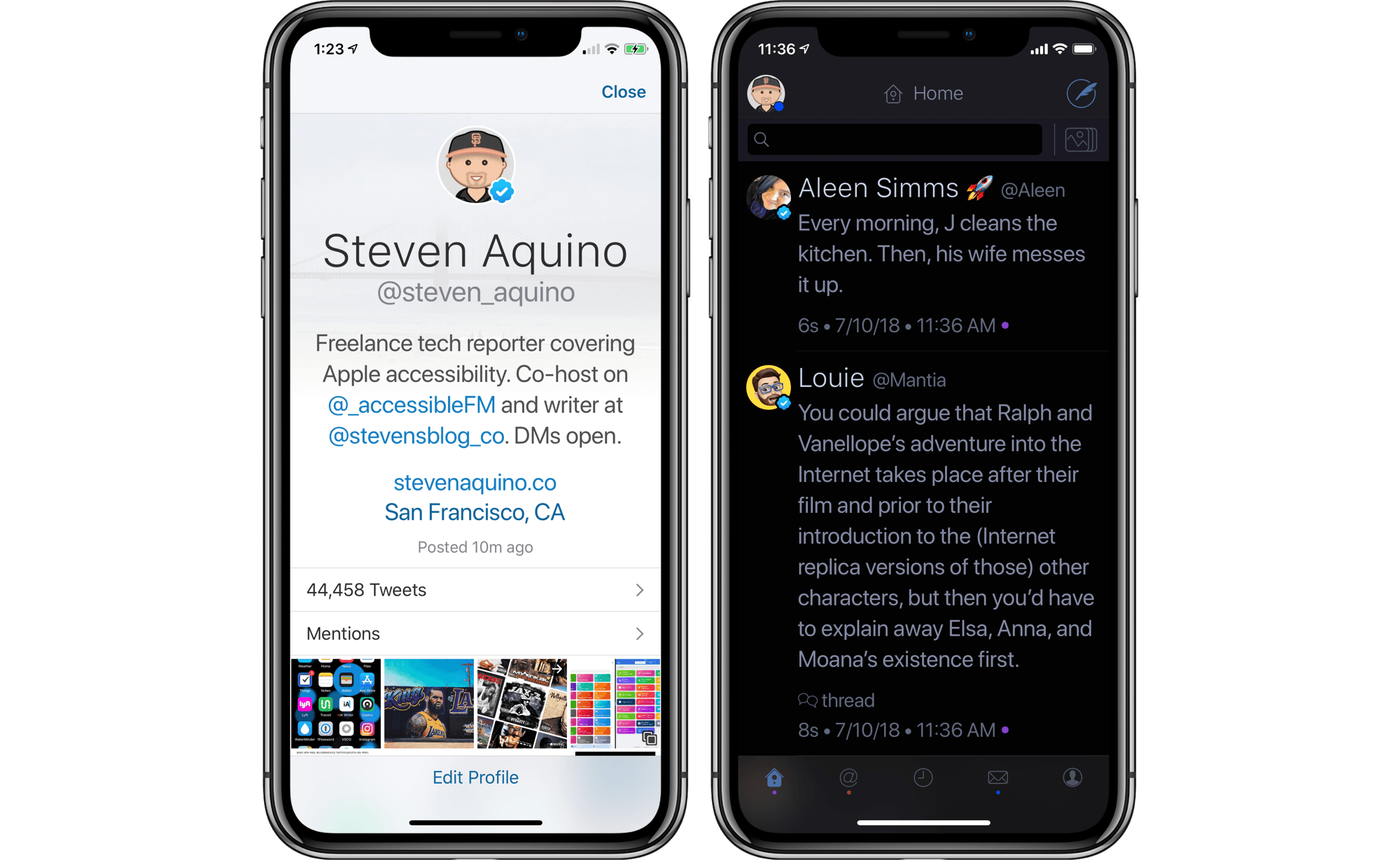

Another notable indie app that does well by accessibility is The Iconfactory’s venerable Twitter client, Twitterrific. AppleVis, a community-run website for blind and low vision Apple users, enshrined Twitterrific 5 into its Hall of Fame in 2016 for what was described as The Iconfactory’s “firm commitment to ensuring continued accessibility of the app, with VoiceOver tweaks and enhancements regularly featuring prominently in app updates.” Like Overcast, Twitterrific is a permanent fixture in Apple’s “Popular Apps with VoiceOver” collection. Also like Overcast, Twitterrific supports Dynamic Type and offers high contrast themes that make digesting Twitter easier for the visually impaired. In terms of accessibility support, Twitterrific is to Twitter clients what Overcast is to podcast players.

Sean Heber, the lead engineer on Twitterrific for iOS and macOS, told me accessibility is a priority at The Iconfactory because the app would “feel pretty broken” otherwise. Blind or low vision users, for instance, couldn’t know if a screen was blank or had buttons to press. He added: “We wouldn’t want to ship a major app with an empty user interface or missing buttons for sighted users, so why should it be any different for anyone else?”

On the value of integrating accessibility, Heber said that while the recognition from AppleVis is appreciated, the reward isn’t in the award. The Iconfactory doesn’t do it for glory; they do it for the sake of inclusiveness. “It doesn’t seem like the kind of thing that should have to be rewarded,” he said. Heber noted he “wishes” disabled users who depend upon accessibility features didn’t need to ask for them. He cited the prevalence of real-world accommodations such as wheelchair ramps and disability-friendly restrooms as things that exist because it’s the right thing to do. That principle of enabling access for everyone applies just as aptly to supporting accessibility in computer software. “They [accessibility features] should be expected and having to provide them should not be resented,” Heber said.

Broadly speaking, what makes Overcast and Twitterrific so compelling is twofold. First, both apps are meticulously crafted, insofar as they’re cleverly designed and adhere well to iOS UI conventions. Secondly, and perhaps most importantly, is both apps are thoughtful and innovative while simultaneously being mindful of accessibility. As a disabled person, I am convinced good design is inextricably tied to accessible design. Accessibility isn’t something developers can or should neglect, or “bolt on” afterwards. Apple set the bar: their products are built with accessibility in mind from the beginning. Developers should take Apple’s philosophy to heart and adapt it to their own processes.

The reality is developers like Arment and The Iconfactory are exceptional cases. Not every developer is so conscientious. The ideal scenario is one where all developers, big and small, create apps that are accessible to all. That isn’t the case, unfortunately, as the App Store contains countless apps that are either at best barely passable or, worse, inaccessible altogether. The mission to advocate and educate for accessibility remains evergreen, which is why the developers mentioned here are such standouts. They see the value in making their apps accessible, and they take the steps necessary to make it happen.

“There really is no excuse not to make your app accessible,” Niemeijer said.

John Ciocca, a WWDC 2018 student scholarship winner and developer of MyVoice, eloquently stated the call to action for App Store developers in a recent piece republished on iMore: “Apps that are inclusive deliver upon an important mission, and that mission is to make a difference by empowering every user. It is our job as developers to integrate accessibility into our projects, because technology is most powerful when it empowers everyone.”

Considering Apple’s Role

Apple’s commitment to accessibility is well-established. The breadth and depth of the accessibility features on all Apple’s platforms is unparalleled in the industry. In this crucial area, Apple is Secretariat at the Belmont. Their staunch support for the disabled community reached new heights with the release of iOS 11 and the top-to-bottom remodel of the iOS App Store.

The redesigned App Store was a marquee feature of last fall’s release, and the revamp was far from only a facelift. A key aspect of the redesign was a stronger editorial focus. Instead of being a relatively sterile storefront that felt transactional in nature, the introduction of the Today tab sought to dig deeper and give context to apps: to tell their stories and the stories of the people behind them. These stories have imbued a liveliness to the store that, more than ever, make it a daily destination.

For accessibility, the App Store has always been a place where Apple highlights popular apps with VoiceOver and commemorates special occasions like Autism Awareness Month and Global Accessibility Awareness Day. These certainly persist today, but Apple’s push for more editorial content on the store really has driven the awareness meter into the stratosphere. The App Store is clearly more about marketing than it is advocacy journalism, but iOS 11’s focus on editorial gave Apple another avenue through which they could put accessibility in the spotlight more often. As I wrote last year, the key point editorially is that anyone browsing the store will, from time to time, see a piece on Global Accessibility Awareness Day or a how-to article on how to use VoiceOver. The sheer fact that the content is there means someone - who may not be familiar with accessibility - will see those headlines and maybe tap to read further if their interest is piqued. Again, Apple isn’t altruistically using its platform solely to uplift the community; the marketing angle to the App Store is undeniable. Nonetheless, that the App Store editorial team chooses to run these stories in the first place matters. After all, there are hundreds of millions of iOS devices in the world, and Apple knows it. The company announced during the WWDC keynote that the App Store receives 500 million weekly visitors, and the editorial team has published more than 4,000 stories that have been seen by more than a million people. It stands to reason that accessibility has ample chance to be noticed, and illustrates how Apple can uniquely leverage its massive reach.

Following in the footsteps of its iOS counterpart, the all-new Mac App Store coming with macOS Mojave later this year presents the same opportunity to boost accessibility’s exposure for Mac users and Mac apps. I suspect the editorial team will take lessons learned on the iOS side and apply them to the Mac.

The Dearth of Accessible Games

Another banner feature of last year’s App Store redesign was the inclusion of a dedicated Games tab. Games are a vital part of the App Store economy, but there’s a critical element to their success that most users (and developers) fail to consider.

The vast majority of games on iOS aren’t very accessible.

An exception is Ryan McLeod’s Blackbox puzzler, winner of the 2017 Apple Design Award in the accessibility category. The win was noteworthy because the app is an accessible game. Unlike others, Blackbox differentiates itself by being fully compatible with VoiceOver, which allows blind and low vision users to play.

McLeod said accessibility is “a core part of the puzzle design process that involves understanding how different kinds of people might interpret a puzzle, what sort of knowledge or tools they might need to be able to solve it.” Moreover, he considers it a personal challenge to come up with new puzzles that are fun experiences for everyone. The mandate to be accessible causes McLeod to look for creative solutions in designing puzzles and their interfaces. “Blackbox is all about creative solutions in the face of adversity, both in making and playing it,” he said.

Like Arment, the road to embracing accessibility for McLeod was a bit like going down a path of enlightenment. “It [supporting accessibility features] was sort of a longer-term, nice-to-have [goal] that I hoped to one day be able to work on so that more people could enjoy Blackbox,” he said. “It took a long time before I fully connected the dots and began to “get” that accessibility wasn’t about a single feature and that it wasn’t about a single underserved audience.” Supporting accessibility in Blackbox became a more personal endeavor to him when he realized features like Dynamic Type helped his father and a friend, both of whom suffered traumatic eye injuries. And a well-planned color scheme for puzzles benefits cousins of his who are color blind.

In an interview at WWDC last year, McLeod told me adding VoiceOver support became imperative after being asked about it by a player on Twitter. “I realized I definitely needed to figure that out,” he said. McLeod explained VoiceOver was easy to implement since Blackbox mostly uses standard UIKit controls. (Developers who use standard UIKit controls in their apps get VoiceOver labels “for free” out of the box). Other elements, he said, were tougher to do as they’re all custom-made for the app.

McLeod shared an anecdote about being awestruck by a VoiceOver demo he received a few years ago from Workflow developer Conrad Kramer. “I still vividly remember sitting in his living room and having this mouth-open moment when I put together how you could still use apps with the screen off [via VoiceOver’s Screen Curtain feature],” he said. McLeod added that this experience, amongst others, helped him see the big picture around accessibility. He soon realized accessibility isn’t just about servicing a specific group; it’s about making Blackbox a better game for everyone, regardless of ability.

Aside from McLeod, another developer who’s working to create more accessible games - though not on the App Store - is For All to Play. For All to Play is an independent studio that aims to, according to their website, “design and develop casual and accessible games” that are playable by people with disabilities.

Their first title, the Kickstarter-funded Grail to the Thief, was released in 2014. It is a text adventure game that makes heavy use of voiceovers and sound effects to make the game playable by the blind and low vision. The game is available on the Mac, but can also be found on Windows, Linux, and Steam.

For Apple’s part, it would behoove them if the App Store editorial team put together an “Accessible Games” collection that highlighted titles that supported system features such as VoiceOver or even Switch Control. It would be a nice complement to the long-standing VoiceOver collection mentioned previously, and would boost the discoverability of accessible games on iOS.

Technical Notes

A common refrain from the developers I interviewed was that Apple’s accessibility frameworks are pretty straightforward to work with, provided the design of your app sticks to stock user interface controls. Niemeijer said the Mac’s accessibility APIs are “extremely powerful” and that in comparison, the iOS APIs are “elegant” given Apple learned from experience building the macOS versions many moons ago. And McLeod is continually impressed by “how much thought and magic is baked into the standard elements and iOS to make most apps fairly accessible out of the box.”

Where Apple can improve, in Arment’s opinion, is that their APIs lack in terms of discoverability and documentation available to developers. McLeod shared similar thoughts, saying in part: “I think there’s still room to go here, especially when it comes to prescribing best practices, providing examples for handling the complex stuff, or exposing us to how others may use our apps.”

Regarding best practices, McLeod made an astute point about Apple’s own iOS apps. Although many users quickly banish these to folders and replace them with “better” alternatives from the App Store, the stock apps retain critical value. The apps Apple bundles with the system “continue to be paragons we reference and rely on, especially when it comes to accessibility,” he said.

The Bottom Line

To reiterate what I wrote at the outset, it’s hard to imagine a world without the iPhone. It’s even harder to imagine the iPhone without the App Store. In many ways, the iPhone’s killer app is the App Store because of all the possibilities it offers.

Ten years later, it’s easy to see what the iPhone and the App Store have contributed to the world. For the disabled community, the App Store has quite literally given us access to the world. Between Apple’s stewardship of its accessibility efforts and the work put in by third-party developers such as AssistiveWare and The Iconfactory, the App Store gives disabled users myriad opportunities to connect with the world and with each other.