The case for native third-party apps on the iPhone was apparent immediately. By creating a device that blends into the background – with functionality entirely driven by software – Apple built a mobile computing platform that could become anything, so long as there was an app to drive the experience. The idea that the iPhone might be limited to a handful of stock Apple apps felt like a horrible waste to developers who were hungry to build their own apps.

When developers arrived in San Francisco for WWDC in 2007, they were eager for news of a native iPhone SDK. Instead, Scott Forstall took the stage and introduced iPhone web apps as Apple’s ‘sweet solution’. It didn’t go over well.

Fortunately, Apple’s flirtation with web apps was short-lived. By the fall of 2007, Steve Jobs confirmed that the company was working on an iPhone SDK for third-party developers, which was released in March 2008.

About four months later, the App Store launched on July 10, 2008, with around 500 apps. Ten years later, the Store offers over 2.1 million. Of course, a lot has happened in between too:

- 2008: The App Store was launched with roughly 500 free and paid apps and games.

- 2009: In-App Purchases were added for paid apps, followed by free apps a few months later.

- 2010: Apple launched its iAd in-app advertising platform.

- 2013: By its 5th anniversary, the App Store featured over 900,000 apps.

- 2015: Apple Senior Vice President Phil Schiller took over responsibility for the App Store.

- 2016: Apple expanded the categories of apps that can use auto-renewing subscriptions, discontinued iAd, and launched a search ads program. Free, time-limited In-App Purchases were also used for the first time to approximate free trials of apps.

- 2017: Apple redesigned the App Store with daily editorial content.

- 2018: As of WWDC, the App Store offered over 2.1 million apps and had paid developers over $100 billion in 10 years.

It’s hard to overstate the meteoric growth of the App Store as a marketplace. Over the course of a decade, the App Store’s history has been dominated by rapid growth and constant change that’s been highlighted by spectacular successes, failures, and controversies. Nowhere has that change been more pronounced than the economics of the App Store. It’s a story that has had a profound effect on the way software is sold and how users relate to the apps they use.

Numbers So Big They’re Hard to Grasp

It’s difficult to imagine now, but in the first weeks of the App Store, it was possible to browse its entire catalog. As Zach Gage told us when we interviewed him for an upcoming episode of AppStories:

I remember, you could actually look at all released games. That was an option. You could just look at everything that had come out, and you could scroll back through…And when I was first starting, I would do that, and I would play literally every game that came out.

That didn’t last long.

Within 3 years the total number of apps stood at 400,000. Halfway through the past decade, there were over 900,000 apps. Today, that number has more than doubled, standing somewhere over 2.1 million apps according to Appfigures estimates. Add to the mix over 20 million registered developers and 500 million weekly App Store visitors, and the numbers become dizzying fast.1

The economic impact of the App Store has been equally impressive. As of WWDC 2018, developers had been paid over $100 billion over the lifetime of the App Store. Even that figure only tells part of the story though. The App Store’s influence is felt well beyond the apps sold. Though not strictly a measure of the App Store’s impact, earlier this year, Apple stated that over the next five years it expects that in the US alone:

- $350 billion will be contributed to the US economy over those five years.

- $5 billion is committed to Apple’s Advanced Manufacturing Fund, up from the previously announced $1 billion.

- $55 billion is estimated to be spent in 2018 alone with domestic suppliers and manufacturers.

Taking an even broader perspective, iOS and Android apps combined are poised to overtake the global film industry’s revenues in 2018 according to Horace Dediu, which is remarkable for something that didn’t exist ten years ago.

Looking into the future, the numbers appear likely to keep growing at a breakneck pace. App analytics company App Annie expects the App Store’s annual revenue to climb to over $60 billion by 2021. That’s astonishing growth, but it seems to be backed up by recent numbers released by Apple, which showed that:

… over 30 percent of all App Store royalties paid to developers in history came in 2017 alone.

The dramatic growth of the Store has had equally dramatic effects on developers trying to build businesses, requiring rapid evolution for their companies to survive. A short-term ‘gold rush,’ where it seemed like anyone could create an app and make money, gave way to fierce competition almost immediately, which led to questions of the sustainability of solo and small-team independent development businesses. Over time, however, the number of business models that are possible on the App Store has expanded, which holds the promise of opening new avenues for developers to build businesses.

It’s still early days for many of those changes and only time will tell to what degree they might help, but looking back on where the App Store has been over the past decade, I’m more optimistic now than I’ve been in a while that although selling apps on the App Store will remain difficult, it will also continue to support sustainable businesses as we enter the Store’s next decade.

Before the App Store

The App Store wasn’t created in a vacuum. Its 2008 debut was preceded by decades of software sales. On Apple’s platforms that meant the Mac, where consumer software sales followed a proven model from the days when apps came on disks in cardboard boxes sold in brick and mortar stores. Consumers purchased software, used it, and paid again for major updates, often at a discount.

The model didn’t change much when software sales moved to downloads over the Internet. Developers gained the freedom to update apps more frequently and upgrade pricing became easier to administer, but the idea of paying for significant updates remained.

When the App Store opened, the idea of upgrade pricing was so ingrained in the software industry that when it wasn’t part of the App Store’s launch, it felt like Apple just hadn’t gotten around to implementing it, but surely would eventually. Ten years later though, the kind of upgrade pricing to which developers were accustomed still isn’t part of the App Store and it has become increasingly apparent that Apple wants to take app business models in a different direction altogether.

Despite starting with simple business models in the Store’s early days, Apple has expanded developers’ options over the past ten years, creating a more varied ecosystem that makes new business models possible. The transition has had its ups and downs, creating opportunities for some developers and tough times for others, but one thing it hasn’t been is dull or static.

The App Store Opens Its Doors

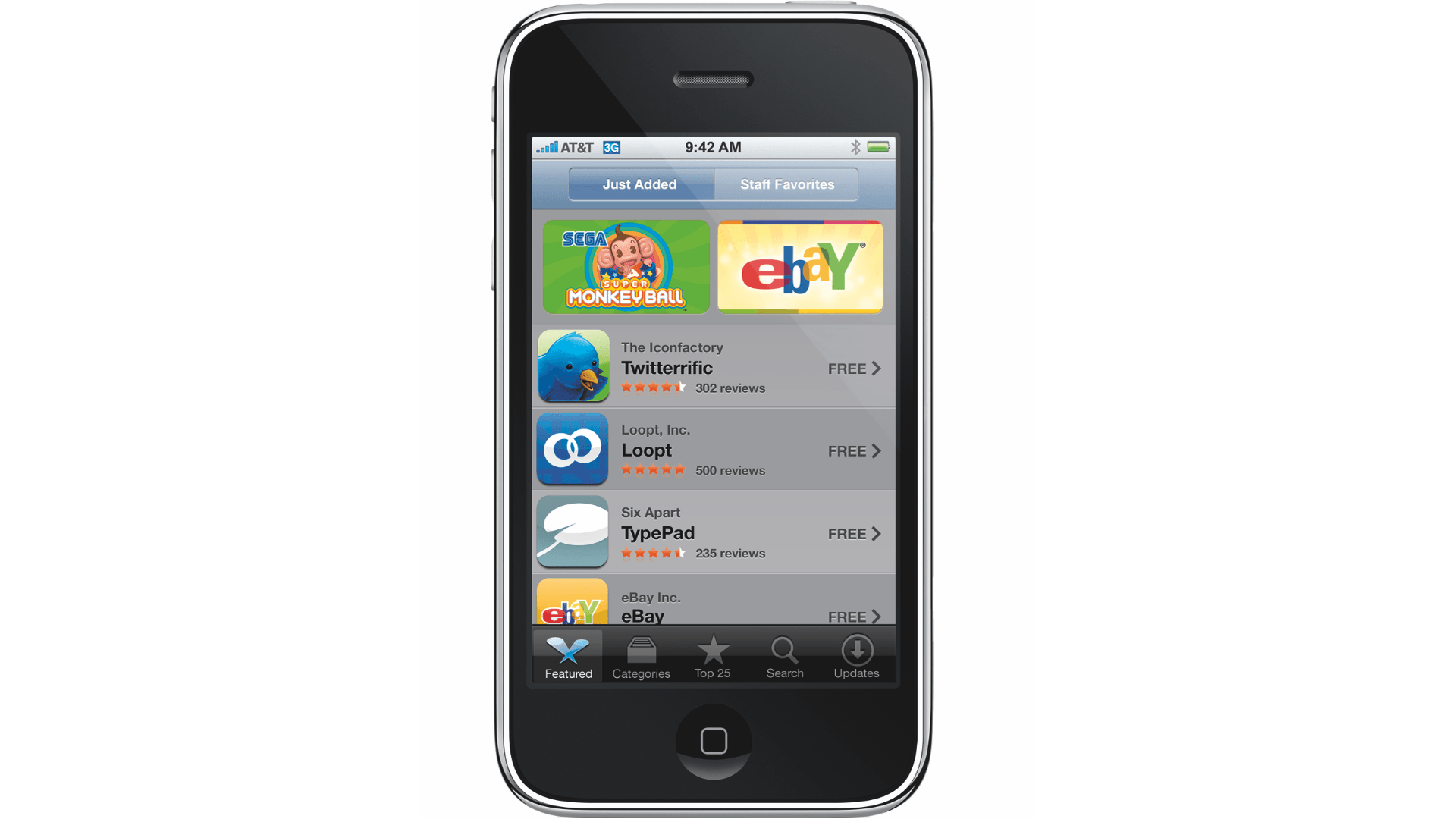

The iPhone SDK was announced in early 2008. At an event in Cupertino, Apple showed off the apps that developers who were given early access to the SDK had made. One was Super Monkey Ball, a well-known game from Sega made initially for the Nintendo GameCube console. Super Monkey Ball debuted at $9.99, a low price compared to most console games and one that seemed to set a psychological price ceiling among developers when the App Store opened its doors – it signaled that iOS apps would cost less than console games and many Mac apps.

In an interview with The New York Times, Steve Jobs detailed the App Store’s initial makeup:

Twenty-five percent of the first 500 applications at the store will be free, Mr. Jobs said. Of the commercial applications, 90 percent will be sold for $9.99 or less, he said, adding that a third of the first wave of applications will be games.

The mix of apps and prices may be different today, but Jobs’ comment reveals in hindsight that the downward pressure on app prices existed from the start.

I Am Rich

The pressure on app prices wasn’t apparent at the beginning. There was enormous pent-up demand for apps that could expand the iPhone’s capabilities beyond Apple’s stock apps. Developers had spent the months leading up to the Store’s launch experimenting with what was possible with the phone’s innovative touch interface and sensors. Many of the early apps such as iBeer, which made it look like you were drinking a pint of beer from your iPhone, felt like demos and novelties, but in some instances, frivolous apps like a $0.99 app that simulated popping bubble wrap served as a launching point to fund more ambitious projects – in this case the hit game Doodle Jump, which went on to sell over 100 million copies.

It didn’t take long for novelty apps to reach their logical conclusion with I Am Rich, an app that cost $999 and didn’t do anything other than display an image of a gem. Apple pulled the app from the sale after eight copies were sold and began taking a harder line against novelty apps, codifying its policies in App Review Guideline 4.3, which addresses ‘spam apps’ without explicitly forbidding them:

Also avoid piling on to a category that is already saturated; the App Store has enough fart, burp, flashlight, and Kama Sutra apps already.

The early onslaught of gimmicky apps is notable primarily as a symptom of chaotic App Store ‘land rush.’ Developers only had about four months to create the first apps for a device with a radically different interface model. Combine that with the fact that many developers had little experience on Apple’s platforms, and it’s no wonder gimmicky apps that were light on functionality dominated the early App Store.

With a seemingly insatiable demand for apps, it wasn’t long before stories of developers creating apps as side projects and making enough money to quit their day jobs became commonplace in the mainstream media. Blog posts from developers detailing their apps’ eye-popping revenue numbers only served to fuel the media frenzy and stoke a hit-driven mentality.

Told far less often were the tales of what happened after the hype surrounding early hits died away. For example, many people remember Trism’s early success but don’t know the story of how its developer spent all of the money made on that game working on a sequel for ten years.

Also untold are the many stories of developers who have quietly built sustainable businesses from app development, earning steady income year after year by growing their customer bases and experimenting with new business models.

Sustainability

From the very beginning, developers expressed concern about the sustainability of businesses built on $1 and $2 apps. The concerns were warranted. As the supply of apps increased, it became apparent that the app gold rush would be short-lived. Soon, those stories of App Store riches were replaced by postmortems about app failures and disappointing sales results.

Developers of paid apps were squeezed on multiple fronts. The steep growth of the number of available apps put pressure on the prices they could charge, as did the increasingly sophisticated offerings from companies that gave away apps as a front end or adjunct to paid services.

In-App Purchases (IAPs) didn’t help either. One of the first App Store business model changes implemented in 2009, IAPs were initially only available as part of paid apps. It wasn’t long before IAPs spread to free apps though, which was a boon for games. However, for categories like utilities and productivity apps that didn’t fit the IAP model as well, the result was merely more downward pressure on prices as customers became accustomed to free apps.

As the years passed, there were still big money-makers on the App Store, but the Store’s perception as a place where easy money could be made was out of touch with reality. An article in the Harvard Business Review from 2015 is instructive. In 2015, there were roughly 1.5 million apps in the App Store. In the 12 months preceding that, just 1,887 of those apps had earned over $1 million and:

Overall, over 20,000 app developers and companies will have made over $100,000 in revenues — or $8,333 per month — from their apps in 2015.

The concentration of earnings is sobering. In addition, over the past several years, the way money is earned on the App Store has shifted dramatically too. As Casey Newton of The Verge observed in 2016 as part of a story on the failure of app developer Pixite:

… for a large swath of these app developers — particularly those without venture capital and sophisticated marketing tactics — the original App Store model of selling apps for a buck or two looks antiquated. In 2011, 63 percent of apps were paid downloads, selling for an average of $3.64 apiece. By last year, a mere 27 percent of downloads were paid, and the average price had fallen to $1.27. Today, profiting from the App Store most often requires a mix of in-app purchases, subscriptions, and advertising.

Those developers who have been able to adapt to the changes have more ways to build a business than ever before, but the shift has left others behind as competition has continued to increase with the ongoing growth of the App Store.

The Power of Free

One of the most challenging aspects of building a sustainable business on the App Store is competing with free. The early days of the App Store were simple. Apps were either free or paid up front.

The reasons free apps took off as they did are as varied as the apps in the Store. There were big companies that used free apps to support paid products and services, hobbyist developers testing the waters of a new platform, startups that wanted to build large user bases quickly and worry about making money later, and developers who hoped to earn more from advertising than they could with a paid up front app. Together, these and other factors put tremendous pressure on app prices.

The march toward free continued with the introduction of IAPs. Developers were able to remove the friction of a payment between them and the users of their apps by making their apps free to download, but with the prospect of selling a variety of in-app digital goods. Although only a small percentage of users pay for IAPs, they are often combined with advertising to create a sustainable revenue stream.

Games in particular benefitted from IAPs. By one account, the 4% of apps that were offering IAPs in 2011 were earning an eye-popping 72% of App Store revenue. Games were already wildly popular on the App Store, but their trajectory took another steep climb with the introduction of IAPs, which allowed developers to sell everything from levels for games to in-app consumables that made games easier to play. The trick became finding a way to entice users who downloaded a free game to buy IAPs, which is where they gained a bad reputation among many people for the manipulative tactics employed by some developers.

As successful as the freemium model has become though, it doesn’t work for all apps. The trouble was that those apps that didn’t fit the IAP or ad model were left to compete in an environment where prices were falling faster than ever. When John Gruber and his colleagues discontinued Vesper in 2016, Gruber wrote:

The market for paid productivity apps for iOS is simply too difficult. There are exceptions, of course.

…

But paid apps for iOS are the exception. The norm is clearly free apps, with in-app purchases.

It was too late for Vesper, but on the horizon were additional changes to App Store pricing models that breathed new life into paid apps.

Moving Beyond Free

In late 2015, Phil Schiller took over responsibility for the App Store from Eddy Cue. We’re not even through two complete iOS cycles of Schiller’s leadership of the Store, but the changes have already been significant. Starting with iOS 10, Apple expanded subscriptions to all app categories and introduced other changes that are reshaping the Store yet again.

Subscriptions

Subscriptions were originally limited to specific narrow categories of apps that delivered periodic content such as issues of digital magazines. In 2016, Apple expanded auto-renewing subscriptions to all apps. To sweeten the deal, Apple stated that the developer’s cut of revenue from a subscription in place for more than one year would be increased from 70% to 85%.

Subscriptions can also include a free trial period and introductory pricing. Those are features that many developers have wanted for paid up front apps since the beginning of the App Store, and are probably a good indication that free trials won’t come to paid up front apps anytime soon.

Although it’s too early to know how subscriptions will play out, they have the potential to act as a useful counterweight to some of the difficulties developers have had selling paid up front apps in an environment of falling prices. Without recurring revenue, paid up front apps have been dominated by single-purpose apps and legions of zombie apps, dragging down the overall quality of the App Store’s offerings. Recurring revenue from subscriptions has the potential to encourage the development of more complex ‘pro’ apps, which not only improves the quality of the App Store’s catalog, but could also help promote Apple’s iPad Pro efforts.

Almost two years after subscriptions were expanded, their adoption only now seems to be accelerating. I suspect that is the result – at least in part – of the backlash among customers caused by some established paid up front apps moving to the subscription model. Apps like Ulysses, which was paid up front for years, had a number of unhappy customers initially as did apps like Zombies, Run!. Adopting subscriptions seems to have been less painful for newer apps like Bear, but anecdotally, every developer I’ve spoken to has been happy with the move despite the sometimes painful transition.

The longer-term benefit of subscriptions is less clear. Too many subscriptions risk triggering fatigue among users who become tired of recurring payments for multiple apps. As a result, subscriptions may wind up being a model that only rewards the leaders of an app category that can successfully make the transition to a subscription model, while making it more difficult for upstart companies to compete with the incumbents. Regardless of the outcome, however, the prospect of recurring revenue for paid apps is a welcome one and something to keep an eye on in the coming years.

Free Trials and Upgrade Pricing: Finally. Sort of.

Subscriptions aren’t the only place free trials are available. The Omni Group (the sponsor of our App Store Anniversary coverage) pioneered a way to offer free, time-limited trials using free In-App Purchases. In late 2016 Omni began offering its productivity apps for free with time-limited IAPs, allowing users to try their apps before committing to pay for them via a paid IAP. Upgrade pricing is also handled using IAPs but requires the old version of the app to be installed to work.

The approach is a clever way around the lack of a more straightforward free trial mechanism and has been used by other apps like MindNode. Black Pixel has even created IAPKit, an open source framework to help other developers follow suit.

The approach isn’t perfect for several reasons. Because it relies on IAPs, the full paid versions of the app aren’t available to others in a family using Apple’s Family Sharing feature. Apps are also listed as free, which can be confusing to customers who don’t realize it’s only free for a limited time. However, as of WWDC 2018, the approach is officially permitted under Section 3.1.1 of Apple’s App Review Guidelines.

I’ve long thought that the ship had sailed on free trials and upgrade pricing. Apple’s move to free trials for subscriptions and the flexibility developers have to change subscription pricing, along with the acknowledgment of Omni’s use of IAPs to approximate free trials and upgrade pricing, raises some doubts in my mind though. On balance, I suspect that Apple is not against free trials and upgrade pricing, so much as it is against the way free trials were done when apps were distributed as shareware or shipped in boxes.

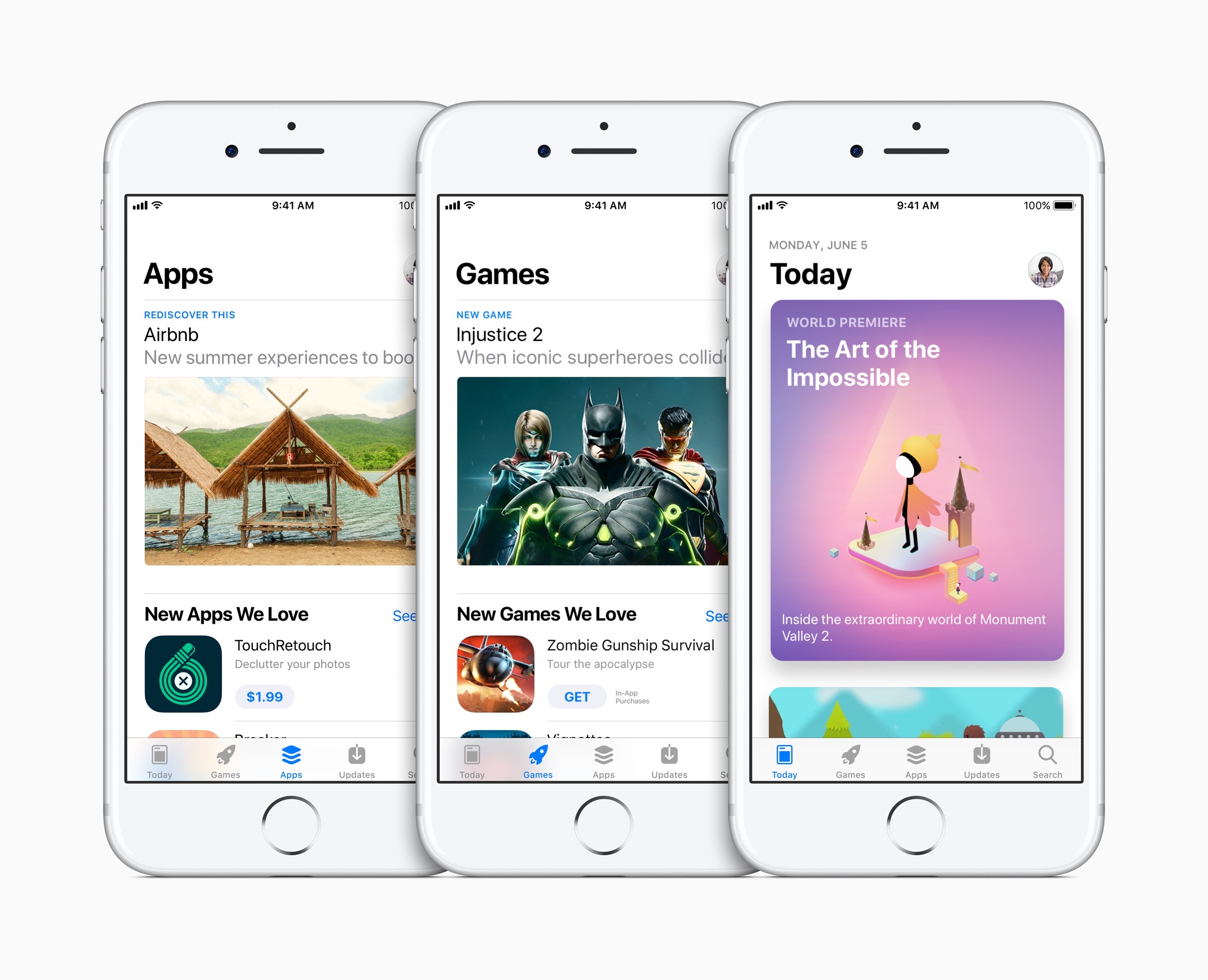

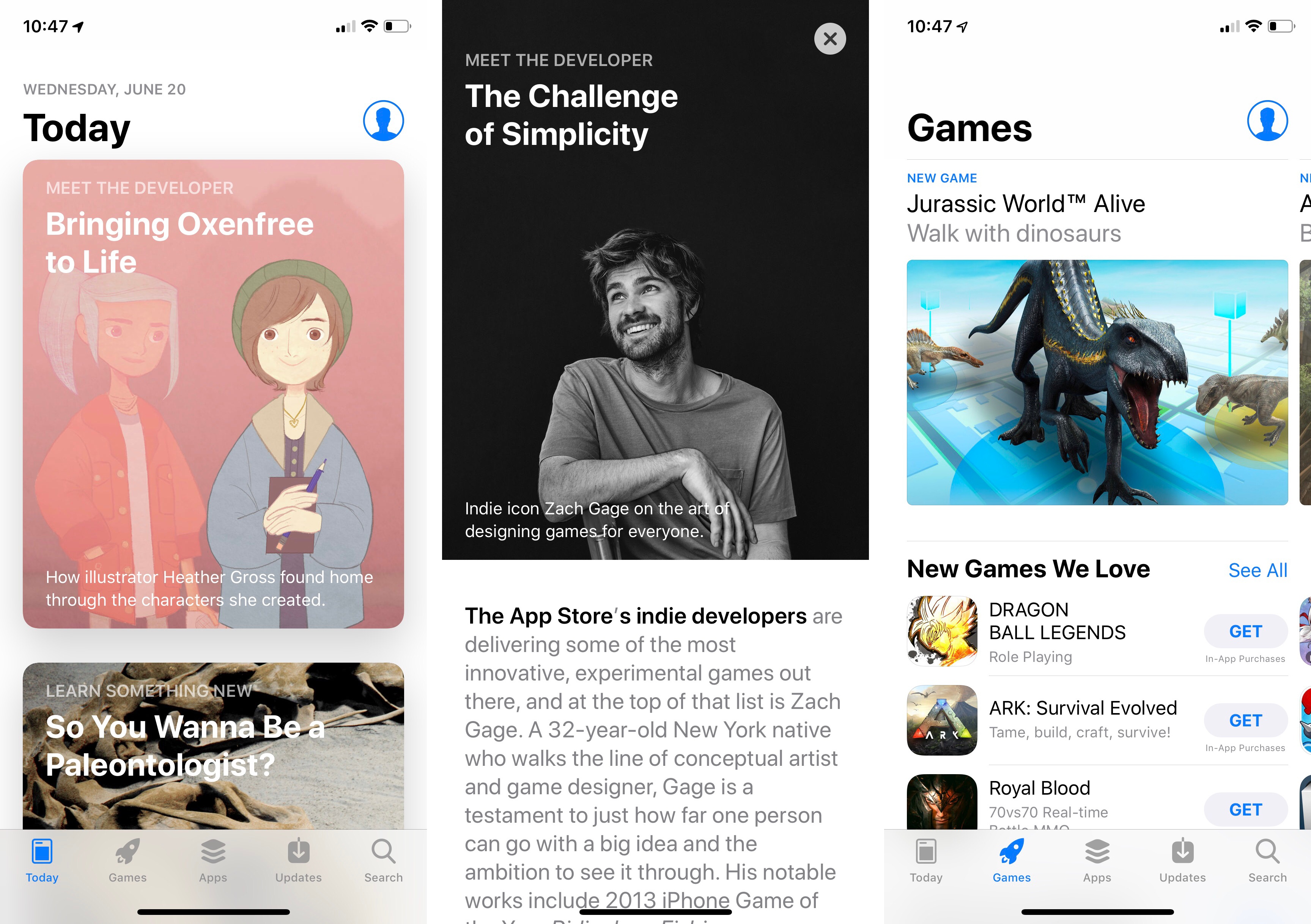

App Store Redesign

Every adjustment that Apple makes on the App Store affects the fortunes of developers in some way. Most of this story has focused on the economic changes that Apple has implemented over the past decade. Among the biggest changes to the App Store was one of its most recent though: the redesign of its storefront with the introduction of iOS 11.

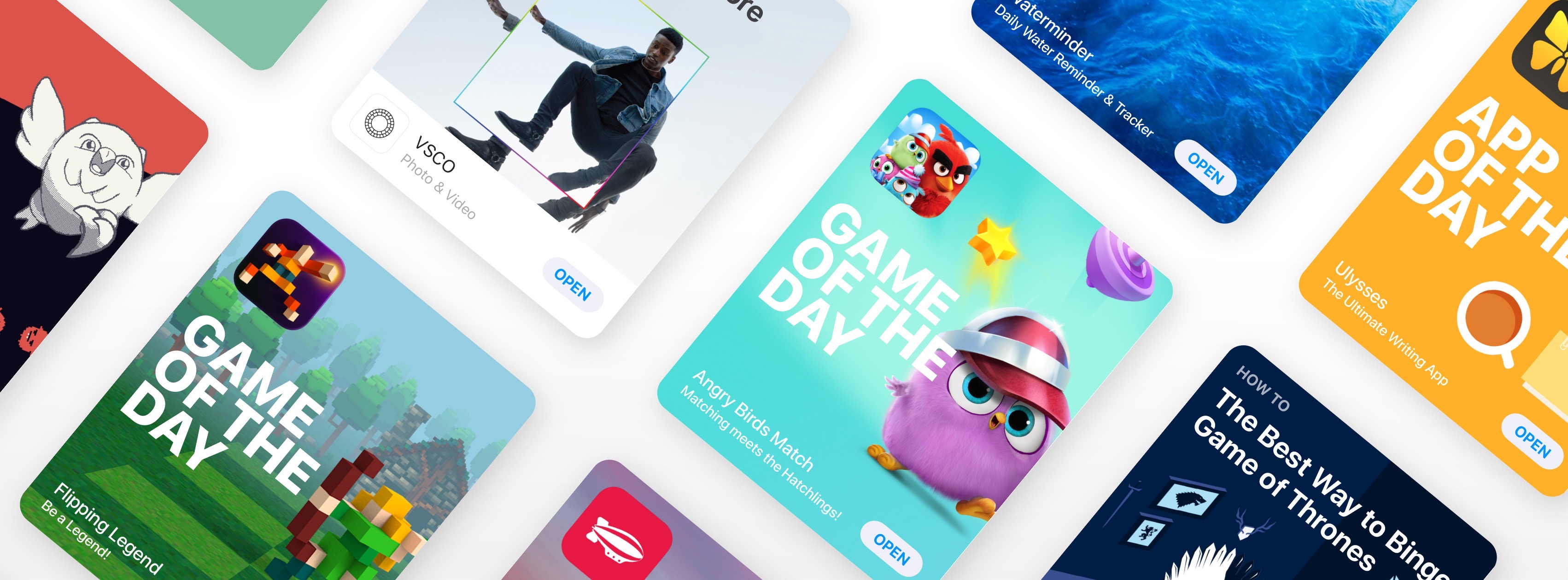

The redesign transformed the App Store into something with a more magazine-like quality, fueled by a focus on illustrated editorial content. Lists still exist, but they’ve been deemphasized. Product pages also got a refresh that puts less emphasis on individual reviews and ratings and provides more ways for developers to promote their products.

According to a report by Sensor Tower as outlined by TechCrunch, the changes seem to have worked, resulting in substantial revenue increases for featured apps:

Sensor Tower’s findings about game downloads line up with research released last month where it found that games that were featured as the “Game of the Day” could see their downloads increase by 802 percent, compared to the week prior to being featured. Apps, by comparison, saw boosts of 685 percent.

Another data point outside the realm of games is Halide, which reported earlier this year that sales have increased 50% since the launch of the App Store update. Although few of the over 2.1 million apps on the Store are named Game of the Day or ever featured as Halide has been, the changes have helped make the App Store a better browsing destination for users than in the past, which should increase overall traffic for all apps.

The one constant over the past decade of the App Store has been change. When the Store opened with 500 apps, it would have been unfathomable to consider the massive size and scope it’s grown to today. Especially in its early years, much of the change was driven by the rapid influx of apps into the Store. Apps and games you could manipulate with your fingers were a novelty that drove large numbers of early downloads.

For a brief time, building apps felt like printing money. The Store was small enough and the demand high enough that it seemed like developers didn’t have to do much more than drop an app onto the Store and watch people snap it up. I don’t believe that was really ever true, but it certainly isn’t true today. With millions of options, marketing is a critical component of app development.

Of course, those early App Store experiences and stories attracted more and more developers to iOS, and as app supplies increased, prices began to fall in an affirmation of basic macroeconomics. The chaos was only increased by rapidly evolving segments like freemium games, which acclimated users to the notion that apps should be free. The constant changes have required developers to be nimble and open to experimentation with different business models to survive.

In the past couple of years though, the direction of the App Store seems to have shifted. Today, the adjustments to the App Store feel more considered and less reactionary to its rapid growth. It’s a maturing of the App Store, and whether you agree with its direction or not, now more than ever, Apple seems to have a vision for how it wants to sell apps going forward. It’s not a roadmap that has been spelled out explicitly to developers, but the resilience of IAPs and the new emphasis on subscriptions show that Apple has a different vision for the sale of apps than was commonplace before 2008.

It’s undeniably difficult to make a living on the App Store, especially for smaller independent developers. However, the expansion of business model options since iOS 10 and the prospect of bringing iOS apps to the Mac makes me optimistic that the App Store – though not without its challenges – will remain a viable way for developers of all sizes and types to succeed alongside one another for years to come.

- These numbers are an order of magnitude greater than any platform enjoyed at the time of the App Store’s debut. According to a New York Times article from the day the App Store launched: “Palm, for example, says that it has 30,000 active software developers, and Microsoft said last month that it had more than 18,000 applications available for its Windows Mobile operating system, which is available from 160 cellular carriers around the world.” ↩︎