Echoes of the past were woven throughout Apple’s announcement that it is transitioning the Mac from Intel-based chips to its own architecture. During the keynote yesterday, Senior Vice President of Hardware Technologies Johny Srouji kicked things off by explaining the balance between performance and power consumption, something that drove the transition to Intel chips nearly 15 years go. Then, Craig Federighi introduced Universal 2 and Rosetta 2, software solutions that originated with the transition to Intel Macs.

It would be a mistake to conclude that the transition to Apple Silicon will be just like the last switch, though. The computing world is very different from 2006, and so is Apple’s lineup of products. The transition carries the promise of powerful, low-power Macs, but it also foreshadows a fundamental change in the relationship among Apple’s platforms that began with the introduction of Mac Catalyst, SwiftUI, and related initiatives. Where precisely these changes lead is not entirely clear yet, but one thing is for certain: the Mac is changing dramatically.

Yesterday, I covered macOS 11.0, known as Big Sur, which is as much a part of this transition as the Mac’s new system-on-a-chip (SoC) will be. Today, however, it’s worth taking a closer look at the hardware that was announced. It won’t be available to consumers until later this year, and the transition is expected to take two years. However, within a week or so, developers will begin receiving test kits that will allow them to start working on supporting the new hardware when the new Macs start shipping.

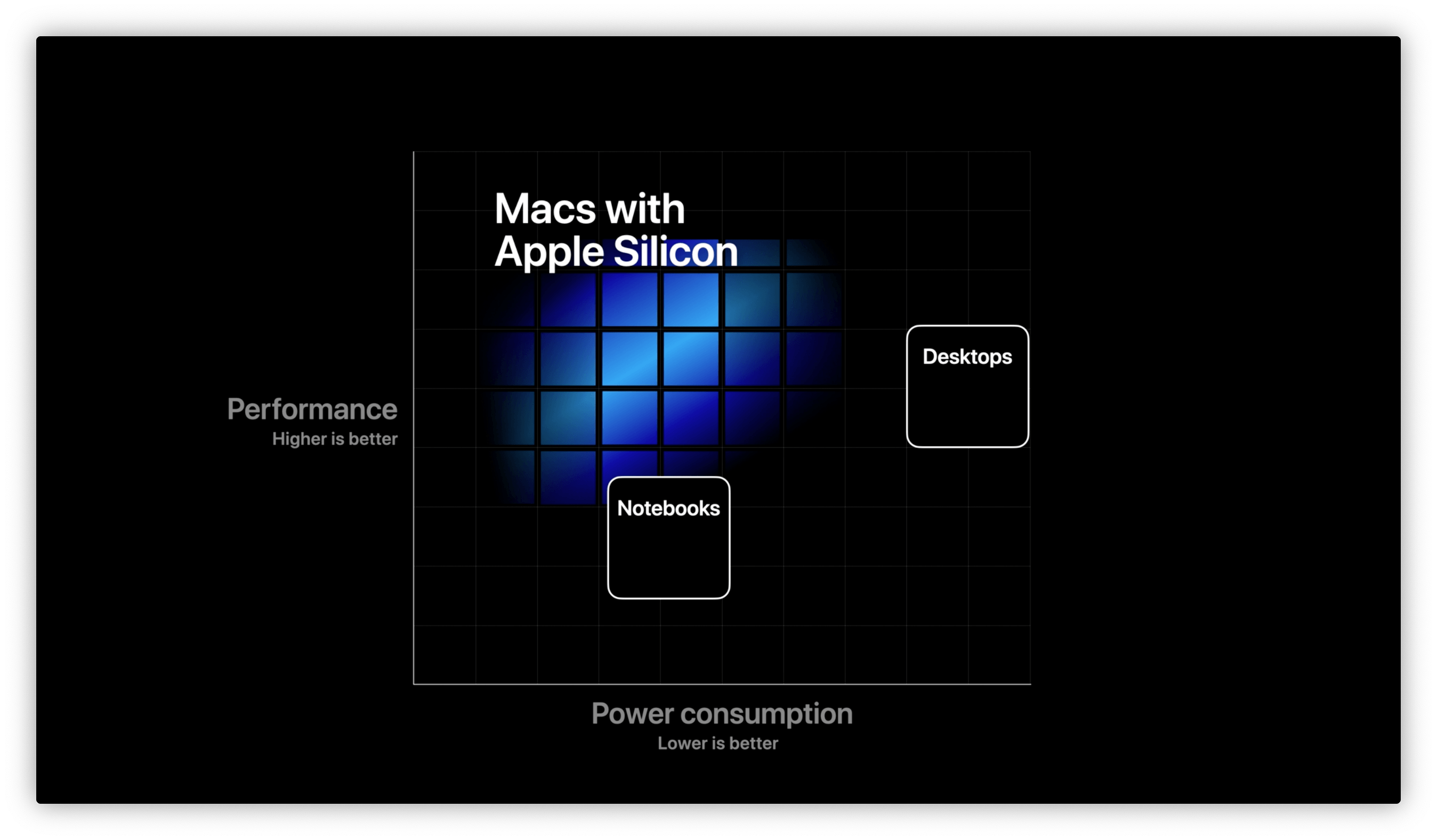

Johny Srouji was clearly excited about the new Mac SoC. He started off by providing some context, explaining how Apple Silicon will allow the company to ship Macs that are both powerful and power-efficient, the same combination that originally fueled the switch to Intel.

It’s easy to forget that Apple has a decade of experience building its own chips for the iPhone, iPad, and Apple Watch. In that time, Srouji says that CPU performance has improved over 100 times, and its GPUs are over 1000 times faster. Combined with lessons learned in developing the Retina display for the iPad, the power-efficient Watch, and the scale of having shipped 2 billion SoCs, Srouji explained that Apple Silicon is poised to deliver high performance in a low-power package.

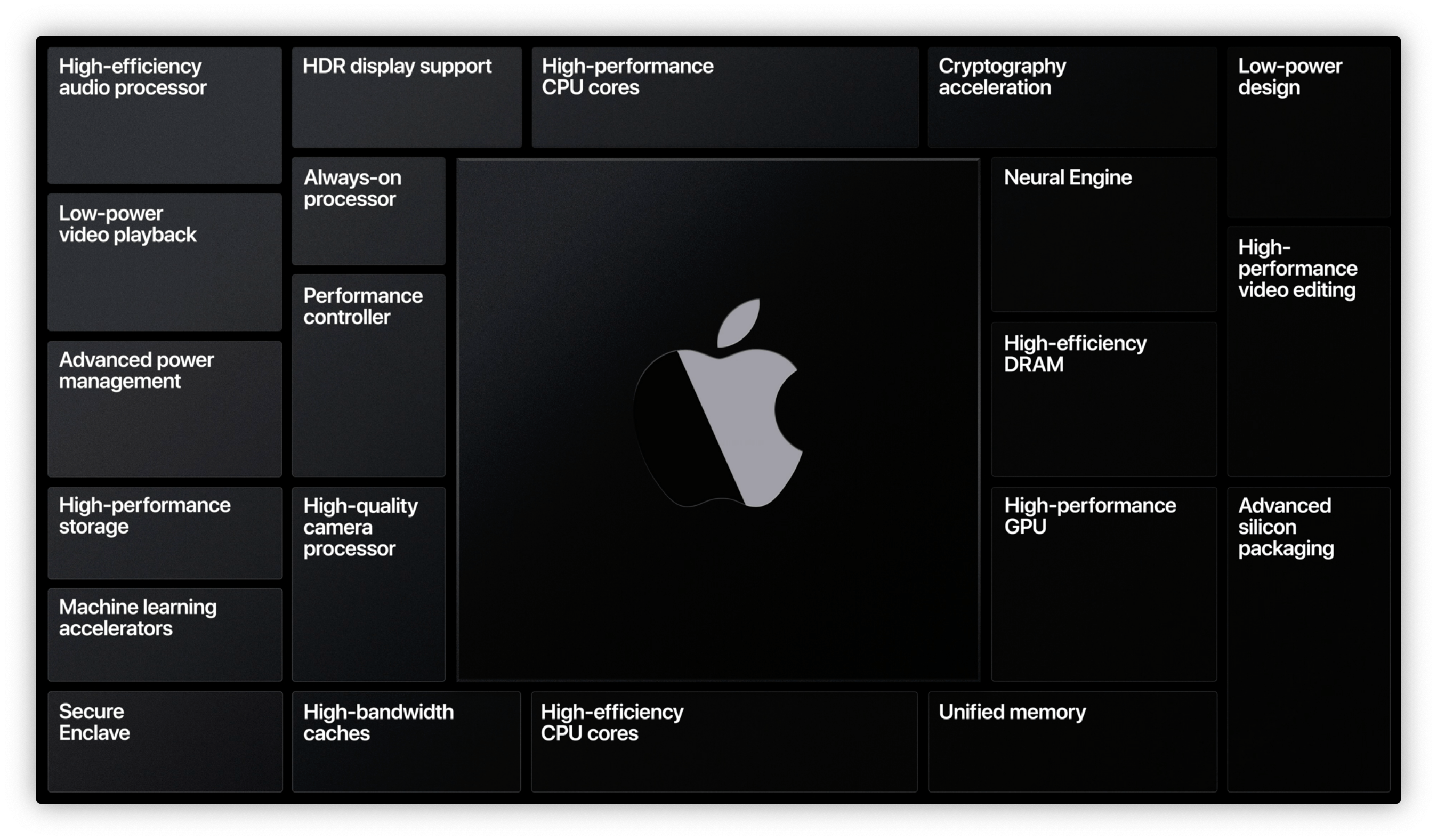

Apple plans to leverage custom features of their chips that were developed for other devices on the Mac.

With a family of SoCs that spans the Apple Watch to the Mac, Apple says it will be able to leverage the technologies it has developed for those other platforms on the Mac. Advanced power management, the Secure Enclave, the system’s GPU performance, and the Neural Engine were all called out features that will enhance apps and games on the Mac. By building on a custom architecture, Apple says it will make it easier for developers to create and optimize apps for all of its devices.

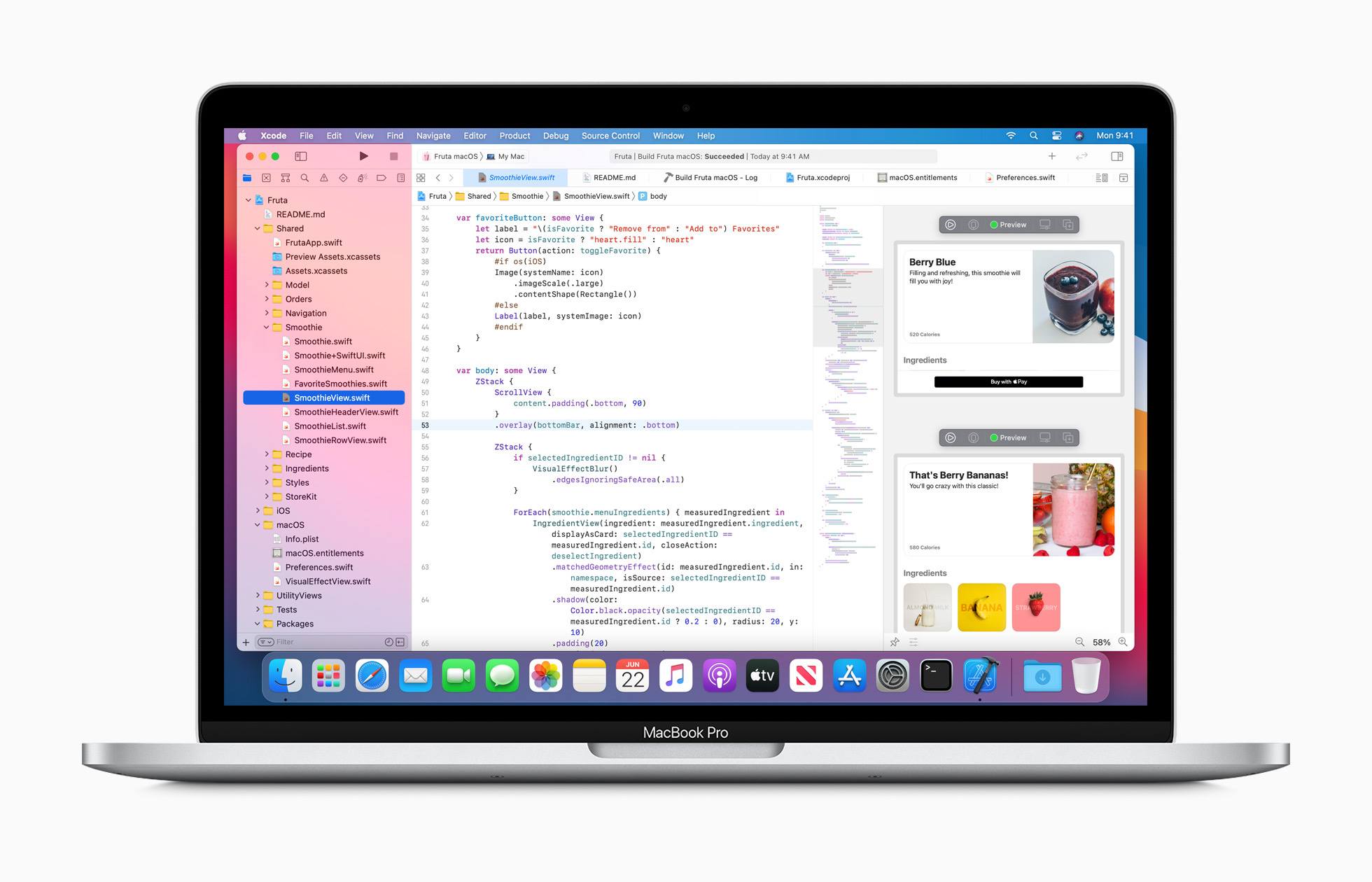

As compelling as Srouji’s pitch for Apple Silicon was, what surprised me the most about the announcement was how far along Apple is with the switch. Federighi took over the presentation to discuss apps, revealing that Apple has already ported all of its apps to run on Apple Silicon, including pro apps like Logic Pro X and Final Cut Pro. The company also announced that Microsoft is working on bringing Office to Apple Silicon, and Adobe is adapting Creative Cloud apps to the new system. Federighi showed off Microsoft Word, Excel, and Powerpoint as well as Adobe Lightroom and Photoshop, plus Apple’s own Final Cut Pro playing three 4K ProRes videos simultaneously.

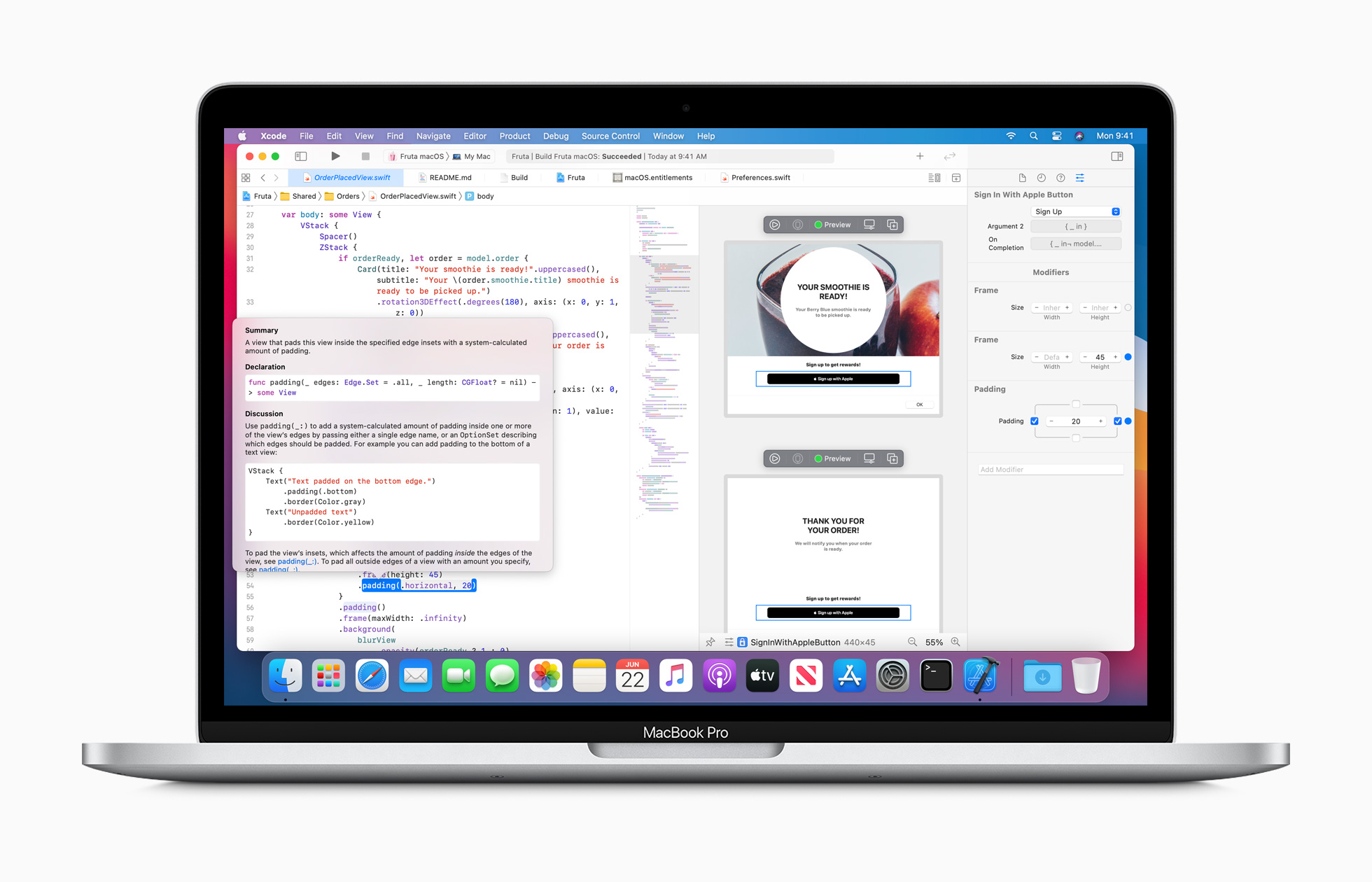

According to Federighi, the process of moving an app to Apple Silicon can be done in a matter of a few days after recompiling for the new system. Federighi also unveiled Universal 2, which will allow developers to build their apps for both Intel-based and Apple Silicon Macs using a single binary.

Apple says existing Mac apps can be recompiled and be ready for Apple Silicon Macs in a matter of days.

Another software transition tool Apple announced was Rosetta 2. The original version of Rosetta was a software layer that dynamically translated PowerPC apps, so they would run on Intel systems during that transition. Rosetta 2 does roughly the same thing, but translation occurs on installation, which Apple says improves performance. When needed, though, Rosetta 2 can also translate code on the fly for things like just-in-time JavaScript compilers. Andreas Wendker, Apple’s Vice President of Tools & Frameworks Engineering, showed off Rosetta running Autodesk’s 3D composition app Maya, and Shadow of the Tomb Raider, a game available on the Mac App Store that uses Apple’s Metal graphics technology.

Apple also announced new virtualization technology that supports Linux and Docker. Windows, however, was not mentioned.

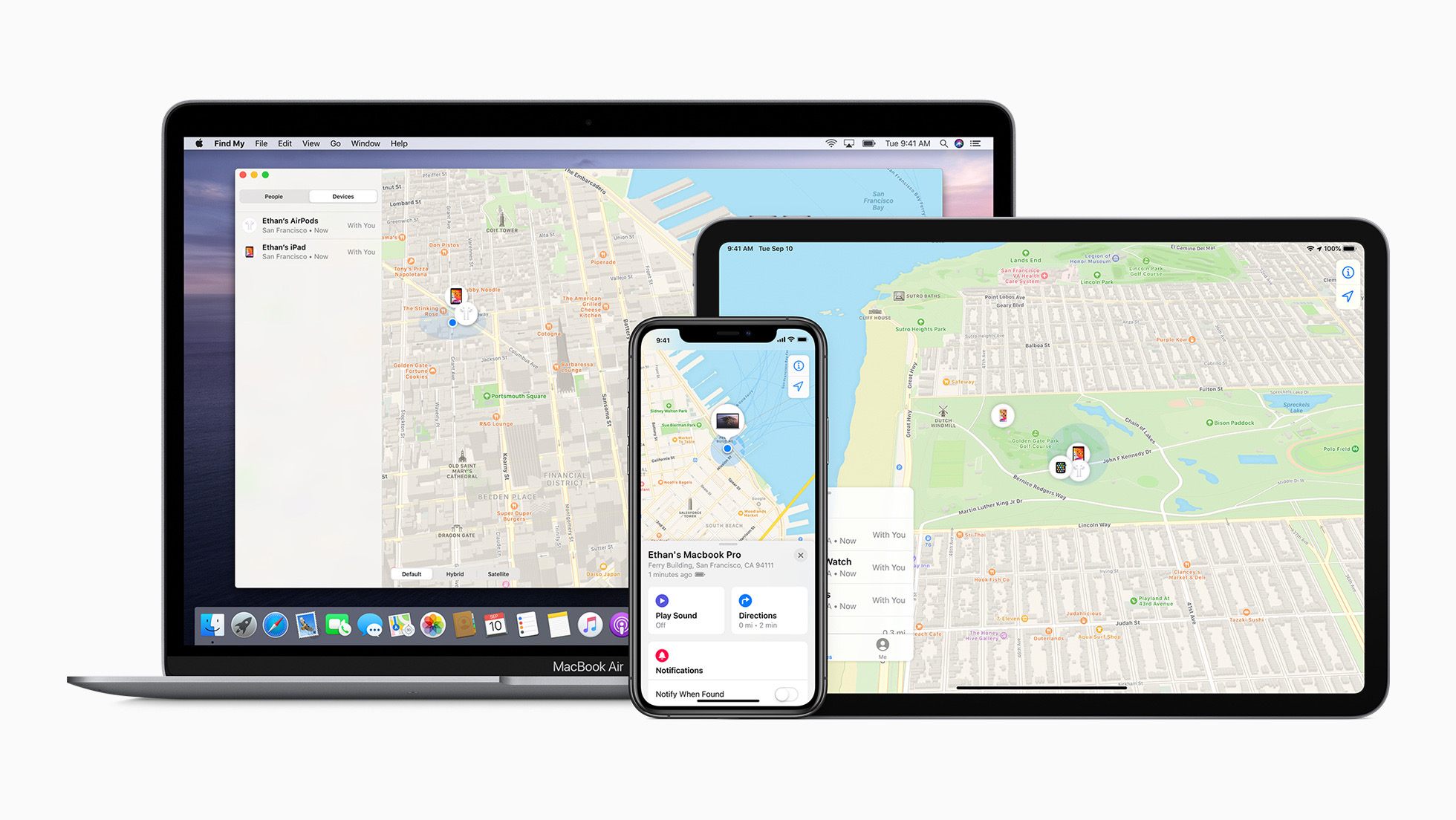

Finally, Apple showed off iPhone and iPad apps running natively on the Developer Transition Kit. Not much was said about the feature, but Wendker demoed Monument Valley 2, a Fender guitar app, and Calm all running on a Mac, which was wild to see, though not surprising given the common underlying architecture. iPhone and iPad apps will be available on the App Store alongside Mac apps for Apple Silicon Macs.

The demos of Apple and third-party apps were all run on the Developer Transition Kit that the company will begin shipping to developers this week. The system is based on a Mac mini but features an A12Z processor, 16GB of RAM, and a 512GB SSD.

Developers will also have access to documentation and sample code, Developer Technical Support incidents, hands-on labs that will happen around the world, and private forums on Apple’s developer website. Developers can apply to the Universal App Start Program but need to have a Mac app. Also, the Developer Transition Kit, which ships this week, costs $500 and must be returned at the end of the program.

Apple has not unified their devices under a common OS, as was once assumed. In fact, with the introduction of iPadOS last year, every Apple device features its own operating system. Instead, the platforms are converging at an app level. Increasingly, the apps people use won’t be dictated by the platform they chose. Instead, they’ll choose the app and then pick the platform that they prefer or that has the combination of hardware features that make the most sense for the task at hand. It’s a subtle shift, but a profound one that I expect will fundamentally change the Mac.

Part of the goal seems to be to unify users’ experience across devices, both through the OS and by bringing iPhone and iPad apps to the Mac. It’s a change that I suspect will make macOS less distinct from Apple’s other OSes, which some users won’t like. At the same time, though, the transition promises to advance the power of the Mac, ushering in a more app-centric approach to computing that eliminates historical quirks of each platform in the service of productivity and creativity. It’s a path fraught with execution risk, but one that I’m glad to see Apple take. We’re a long way from the final destination still, but what’s on the horizon is exciting and full of promise.

You can also follow all of our WWDC coverage through our WWDC 2020 hub, or subscribe to the dedicated WWDC 2020 RSS feed.