Later today, Epic Games and Apple will square off in a high-stakes trial in US federal district court that’s nominally about money. However, if that were all that was at stake, the claims each company has made against the other would likely have been resolved by now. Companies the size of Apple and Epic settle because it’s rarely in their interest to have a judge make decisions for them. However, this trial is different.

There’s more to these disputes than Epic’s allegation that Apple violated antitrust laws and Apple’s claims that Epic violated its developer agreement. Underlying it all is the way the dispute was precipitated by Epic. The Fortnite creator’s actions don’t necessarily absolve Apple of antitrust violations, but Epic’s calculated orchestration of events leading to the dispute have not gone unnoticed by the judge presiding over the case and may influence the trial’s outcome. Coupled with Epic’s efforts to get regulators around the world to take up its cause and its very public crusade against the way Apple operates the App Store, it’s not surprising that the claims haven’t settled. Instead, the parties will begin today with opening arguments in front of US District Judge Yvonne Gonzalez Rogers, who the parties have agreed will decide the dispute instead of a jury.

Regardless of your opinion of the way Apple runs the App Store or Epic’s litigation tactics, the thing to keep in mind as the trial starts is that the judge is being asked to settle a legal dispute, not set policy. Both companies have made specific claims against the other, which by definition means the judge’s ruling will likely be narrower in scope than it would be in an antitrust case brought by the US government. Nor is any remedy imposed by the judge likely to be as broad as government regulation of the App Store might be someday.

Still, that doesn’t mean the stakes aren’t high; they are. An adverse ruling against Apple could significantly change the way the company operates the App Store and would likely trigger more antitrust lawsuits and regulatory scrutiny in the future. As a result, I thought it would be useful to dig in and take a closer look at some of the parties’ arguments and the context in which this dispute arose to provide a better sense of what to expect from the trial, which is expected to run about three weeks, and what the outcome might be.

How Did We Get Here?

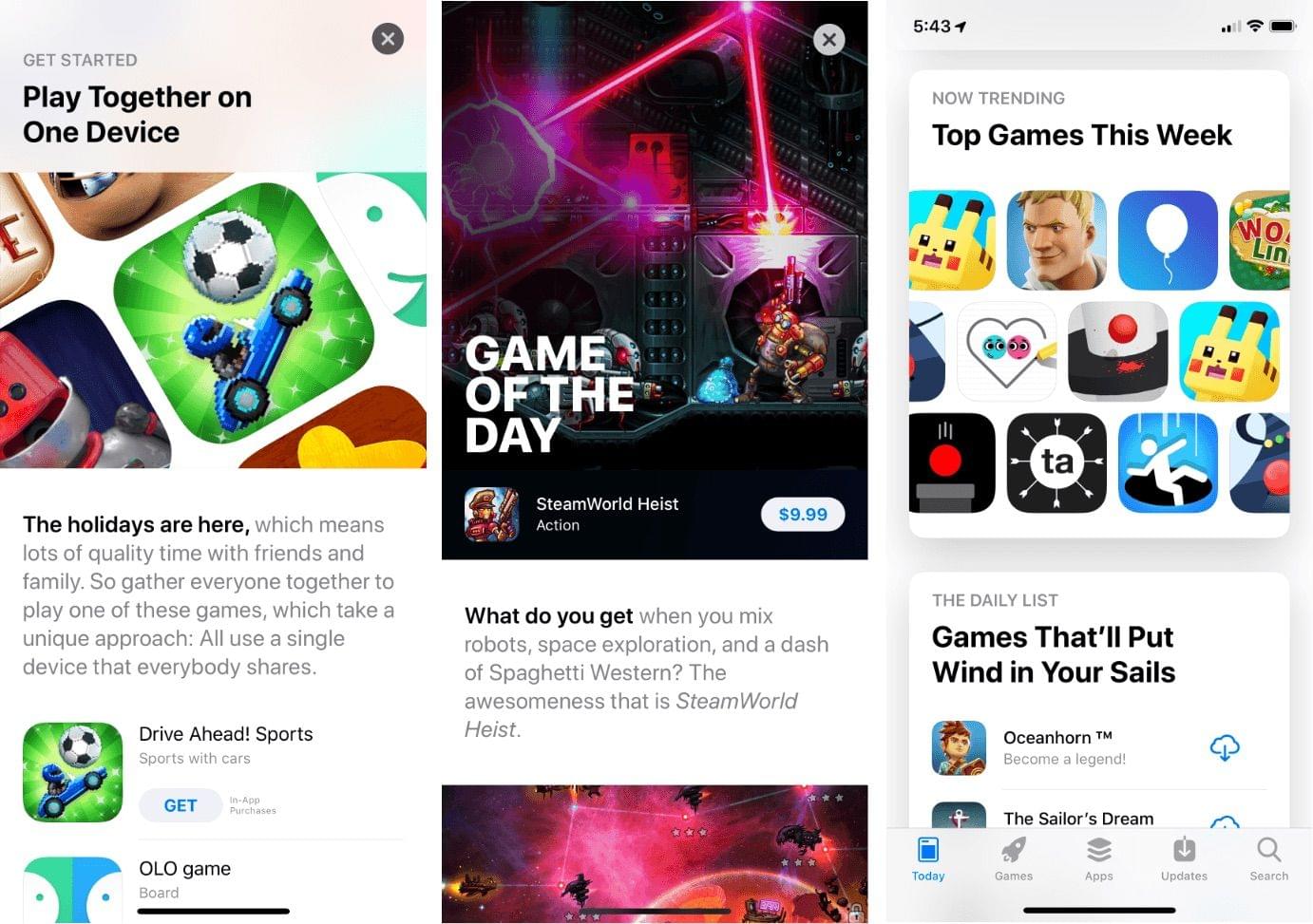

Epic and Apple’s relationship wasn’t always as contentious as it is today. Fortnite was frequently spotlighted in the App Store.

The events leading up to Epic’s antitrust suit against Apple are worth keeping in mind because they could affect the outcome of the case. Epic is the maker of Fortnite, a popular videogame that is available on multiple platforms. It started out on consoles, PCs, and Macs but eventually made its way to mobile platforms, including iPhones, iPads, and Android devices. Although Fortnite was undeniably popular on Apple devices, numbers revealed in the lead-up to the trial show that the revenue generated by Fortnite on Apple’s platforms is small relative to other platforms like Sony’s PlayStation console.

Fortnite is a free-to-play game, but players can purchase in-game currency called V-Bucks to buy digital goods like skins for their characters. Apple’s developer agreement and App Review Guidelines require that digital goods like V-Bucks can only be sold using the App Store’s In-App Purchase system, from which developers must pay Apple a 30% fee.

Despite having agreed to the terms of Apple’s developer agreement, Epic decided it wanted to sell V-Bucks directly to consumers, bypassing the App Store’s In-App Purchase system and its 30% fee. Last August, Epic submitted an update to Fortnite to Apple’s App Review for approval. On August 13, 2020, after the game was approved and available to users, Epic made a server-side change that enabled a new in-app payment system in violation of Apple’s App Review Guidelines that circumvented Apple’s commission on digital goods.

That same day, Apple removed Fortnite from the App Store, and Epic immediately sued Apple in US District Court for antitrust violations. Epic also published a protest video on YouTube parodying Apple’s 1984 TV commercial that introduced the Macintosh computer to mock the company and rally public support for Epic’s legal efforts. The timing of events left little doubt that Epic’s actions were part of a highly-choreographed strategy to challenge Apple’s App Store rules publicly and in the courts.

In hindsight, the events of last August were even more carefully orchestrated than many first imagined. In the course of the discovery leading up to trial, it was revealed that the events were part of a multi-month coordinated effort dubbed ‘Project Liberty’ that involved hundreds of Epic employees, a team of outside lawyers from New York mega-firm Cravath, Swaine, & Moore, and a PR firm.

There is no legal prohibition against formulating a business strategy with the assistance of professionals to deal with a competitor. However, Epic’s actions arguably demonstrate a level of bad faith that could undermine its antitrust case, something Judge Gonzalez Rogers has essentially suggested at previous hearings. A very old legal principle that is known as the doctrine of ‘unclean hands,’ which Apple has raised and is based on the equitable notion that manufactured disputes should be discouraged, could prevent Epic from winning some or all of its claims, regardless of their merits.

It’s hard to imagine Epic’s actions not affecting the outcome of the trial. Epic could have submitted an update of Fortnite that included its own payment system to App Review, and when it was inevitably rejected, sued Apple for antitrust violations. Instead, Epic chose to deceive App Review, intentionally triggered its payment system remotely, knowing it was against the terms of its developer agreement and would likely result in Fortnite being pulled from the App Store. Epic’s intentions were driven home by its coordinated lawsuit and PR blitz, which it unleashed immediately upon Fortnite’s removal from the App Store.

Separate and apart from the merits of Epic’s claims, I find these tactics incredibly distasteful and grounds in and of themselves to deny some or all of the relief Epic seeks. The courts should be reserved for good-faith disputes, not conflicts designed to maximize drama. Although I doubt the doctrine of ‘unclean hands’ is sufficient by itself to counter Epic’s antitrust claims, I do think it should be a factor that weighs against Epic. We’ll see soon enough if Judge Gonzalez Rogers agrees.

Defining the Market

Chief among the mix of federal and state antitrust laws that Epic accuses Apple of violating is the Sherman Act, which was enacted in 1890. As the US Federal Trade Commission summarizes it:

The Sherman Act outlaws “every contract, combination, or conspiracy in restraint of trade,” and any “monopolization, attempted monopolization, or conspiracy or combination to monopolize.”

The law itself is deceptively simple in its language, but it and over a century of case law interpreting it implicates a myriad of complex economic considerations. That’s why Epic and Apple have hired a legion of distinguished economics experts to testify on their behalf. The underlying economics are so important that it’s likely at least a week of the trial will be dedicated to nothing but expert testimony.

It’s easy to get deep in the weeds when it comes to the economics of antitrust, but I think it’s fair to say that most cases are won or lost on how the relevant market is defined. That’s because the more broadly you define the market, the easier it is to find that there’s competition, and therefore, no monopoly.

Unsurprisingly, Epic argues in favor of a narrowly defined market, while Apple believes something broader is in order. Epic claims Apple is monopolizing two markets: (1) iOS app distribution and (2) In-App Purchases, both of which strike me as stretches.

Epic argues that iOS app distribution is the first relevant market because once a customer decides on iOS as the OS for a mobile device, they are effectively locked into Apple’s ecosystem giving the company monopolistic control over the apps available for that platform. That argument is tortured on a couple of levels.

Epic’s argument is simultaneously too broad and too narrow. Epic’s market definition is too broad because the company argues the relevant category is all apps, not just games. There are lots of apps you can only get on the iPhone, and if that was the appropriate market to analyze, it would make Epic’s argument more appealing. However, Fortnite is a game, and I think most people intuitively understand that games are different creatures from other apps. Games typically use custom UI that looks similar wherever the game is played, making competing platforms more approachable and better substitutes for an iOS game than a typical iOS app. The business models that work with games are also different than what works with other apps. For example, games rely heavily on advertising and rarely employ subscriptions compared to other apps.

The problem for Epic is that the game at the center of this controversy is Fortnite, which you can play on multiple devices from Sony and Microsoft consoles to PCs and, soon, in a browser on iOS and elsewhere with the NVIDIA GeForce Now service. Couple that with the fact that the iPhone was a relatively small part of the revenue generated by Fortnite, along with the fact that V-Bucks are available and cross-play is possible via competing platforms, and it’s hard to see how the appropriate market isn’t videogames.

Of course, Epic disputes that these factors are relevant, but that strikes me as an uphill battle. It’s also notable that Epic CEO Tim Sweeney claimed the exact opposite of the position the company has taken in its lawsuit as recently as 2018. That year at the Game Developers Conference, Sweeney told Rolling Stone for a story that is no longer on the web, but which I covered in Game On: A Decade of iOS Gaming, that:

“Right now we are ten years into the mobile gaming revolution. This is a revolution that’s brought more than 3.5 billion new computing device owners into the market in the form of smartphones and tablets and billions of new gamers. So it’s one of the greatest events in the history of the game industry.”

Almost more importantly, though, Sweeney noted that while that 2008 event initially split the game industry into two halves - high end gamers and gaming and casual gamers - a new trend “upending the game industry” is seeing that split disappear as the games made for consoles or computers are now showing up nearly unaltered on smartphones.“

I guess he changed his mind.

Second, although it’s not unheard of, markets are rarely defined as a single type of product: here, iOS apps. That’s because defined narrowly enough, almost any market seems like a monopoly. For example, suppose someone came to us at MacStories and said, “I want you to publish my story,” and we declined. Have we violated antitrust law? The answer is obviously ‘no’ because there are many ways to publish an article on the web, but at the same time, there’s only one way to publish a story on MacStories. I recognize that this isn’t a perfect analogy, but it does illustrate the importance of not defining a market too narrowly. Epic may not be allowed by Apple to release its game with its own payment system on the App Store, but there are many alternatives ways to get it in the hands of customers, including the myriad of ways Fortnite is already available.

Epic’s claim that Apple monopolizes the market for In-App Purchase transaction processing seems like an even greater stretch. In-App Purchases happens to be the way Epic has chosen to monetize Fortnite, but it’s not the only choice on the App Store. Moreover, digital goods sold on other platforms can be used in iOS games whether or not they’re purchased there. It’s hard to imagine the Court requiring Apple to permit alternative payment schemes when single storefronts are the standard across virtually all digital stores.

I’ve spent a lot of space covering Epic’s attempt to define the markets it says Apple is monopolizing. There are, of course, many other elements that must be proven before the Court can conclude that Apple has monopoly power and abused it. However, the market definition will likely occupy more time than probably any other single issue during the trial, which is why it deserves an outsized amount of attention.

I have a hard time seeing the Court siding with Epic’s definition of the relevant market. The wildcard here, though, is that platform-specific marketplaces like the App Store don’t fit neatly into traditional market definitions for antitrust law. That’s not something Epic, Apple, or even the judge has any control over, but on balance, I think it favors Apple. That doesn’t change the fact that the App Store could be run better. Many of the criticisms of the App Store are valid and should be addressed by Apple or perhaps through government regulation, but what Epic’s tortured arguments make clear is that antitrust is not the best way to address the App Store’s deficiencies.

Epic’s path to victory is far from certain. They have the advantage of having the cash to wage the battle with equally qualified attorneys and experts. However, at the end of the day, Judge Gonzalez Rogers will weigh the facts presented by the witnesses and apply them to the law as it applies to Epic and Apple. The App Store itself may be on trial in the court of public opinion, but the issues in dispute before the judge are far narrower. I suspect that will leave many of Apple’s critics dissatisfied regardless of the result, especially since with inevitable appeals, the next few weeks is just the opening round in what promises to be a much longer dispute.

However, while the outcome of Epic’s lawsuit may not satisfy App Store critics, the intense scrutiny will likely be a force for positive change regardless, as we’ve already seen with changes such as modifications to the App Review Guidelines and the Small Business Program. Apple would undoubtedly deny those changes were made in response to the pressure of litigation, but it’s hard to imagine that the lawsuits and interest of regulators around the world haven’t at least influenced some of the positive changes to the App Store, which is a step in the right direction to making it a better option for all developers.