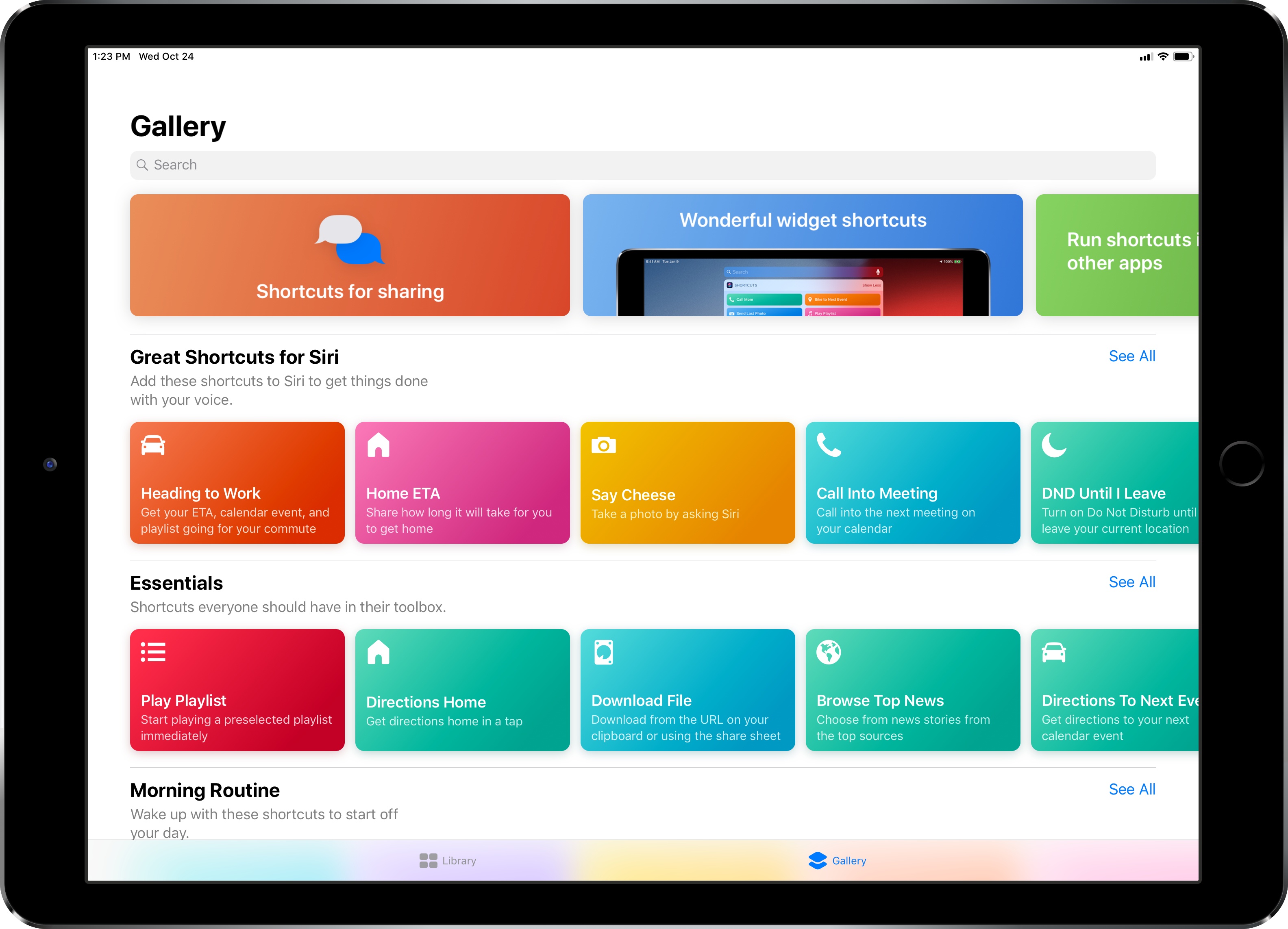

Since it was announced at WWDC over the summer, the lion’s share of conversation around shortcuts has been about getting things done quickly and efficiently. Apple’s marketing message focuses on how shortcuts in iOS 12 help “streamline the things you do often” using Siri and/or the Shortcuts app. The company also recently put out a press release highlighting top App Store apps that have integrated shortcuts to extend their functionality, touting them for “making [users’] favorite apps even easier to use with a simple tap or by asking Siri.”

While the convenience factor of shortcuts is appreciated, an important aspect to their utility is accessibility. It’s a crucial aspect of the story around shortcuts, because while everyone loves a time-saver or two, these workflows also have the potential to make iPhone and iPad more accessible. In an accessibility context, shortcuts can be lifesavers in terms of reducing cognitive load, excessive swiping and tapping, and other common points of friction often met by disabled users.

Shortcuts, Past and Present

Before considering shortcuts as an accessibility tool, it’s important to understand their roots in order to properly frame them into perspective. The idea that shortcuts, or workflows, can prove valuable as an assistive technology isn’t a novel one.

Workflow, on which the Shortcuts app is based, was acquired by Apple in early 2017. Two years earlier, however, Apple selected Workflow as an Apple Design Award winner primarily for its integration of iOS accessibility features. Ari Weinstein, who joined Apple to work on Shortcuts post-acquisition, told me in an interview at WWDC 2015 that he and his team received feedback from several blind and visually impaired users who were curious about Workflow and wanted to try it. As a result, the team felt adding VoiceOver support was “the right thing to do,” Weinstein said.

To paraphrase Kendrick Lamar, Shortcuts got accessibility in its DNA.

Given the history lesson, it’s not at all far-fetched to think the Shortcuts app would have appeal to disabled users. Like Overcast and Twitterrific, Shortcuts is an app built for the mainstream, yet it has the care and design sensibility to carry relevance for a variety of use cases, like being fully accessible to a blind user via VoiceOver. This isn’t small potatoes; given Apple’s commitment to the disabled community, it’s certainly plausible Workflow’s ode to accessibility made the app all the more desirable.

More Than Just Productivity

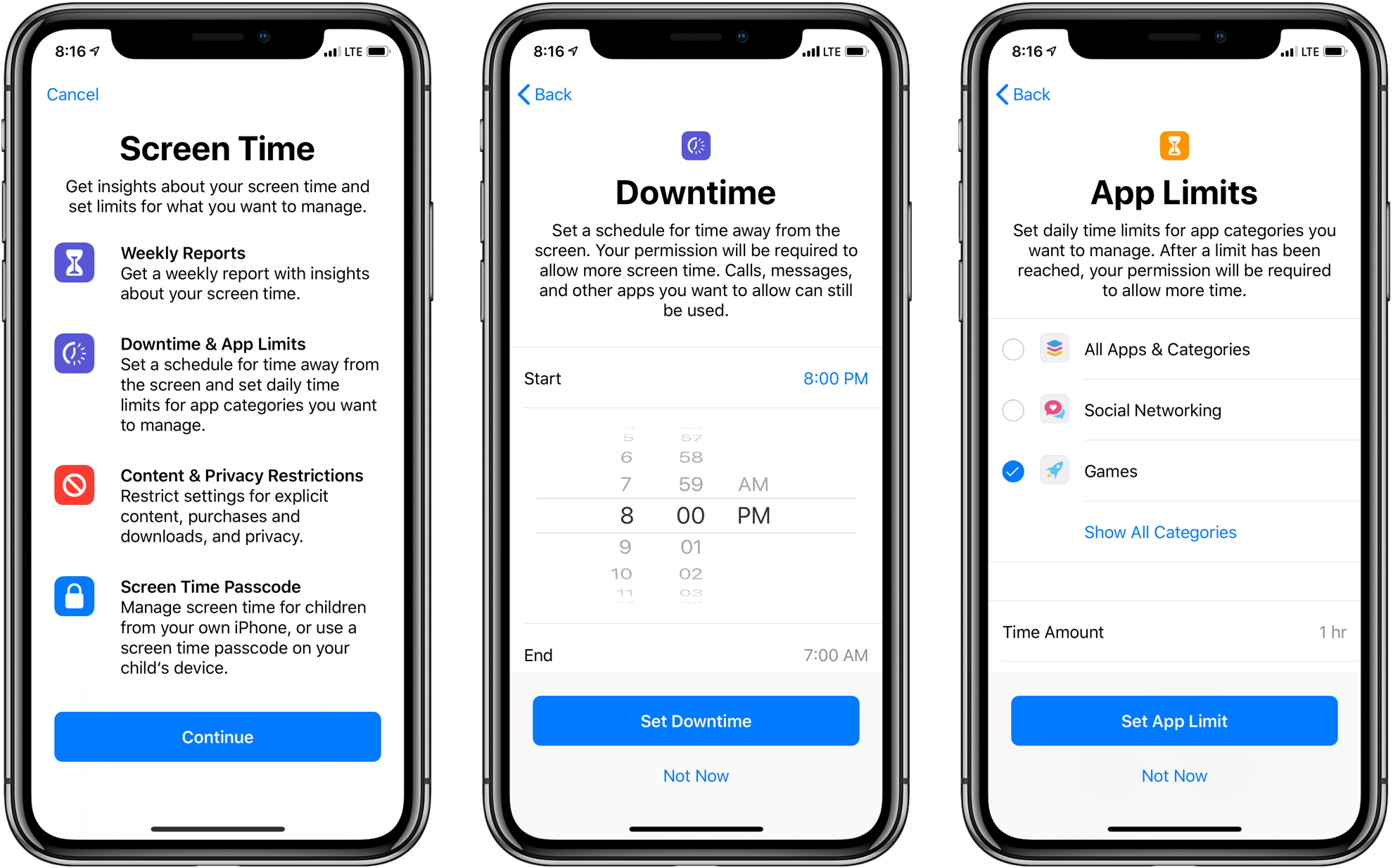

As I reported during WWDC, Apple’s focus this year, software-wise, marked a departure from how they’ve traditionally approached accessibility enhancements. Unlike past years, there were no new discrete accessibility features for any platform. (AirPods with Live Listen is close). Instead, Apple chose to hammer on the idea that the tentpole features (e.g. Group FaceTime in iOS 12, Walkie-Talkie in watchOS 5) can be enabling technologies. The overarching theme of the conference was that the new features were so well designed that they brought inherent accessibility gains.

Siri shortcuts is another of those features. In my briefings with Apple at WWDC and since, shortcuts has been one of the first items they wanted to discuss. Like Group FaceTime and others, the company firmly believes in shortcuts’ potential as an accessibility aid. Their enthusiasm is warranted: for many users with certain cognitive and/or physical motor delays, the consolidation of tasks can reduce friction associated with remembering how to perform a task and then doing it. In this way, shortcuts are the inverse of task analyses; rather than extrapolating tasks into their individual parts (e.g. tapping a series of buttons in an app), the Shortcuts app’s automation turns them into a single step. (You break down steps when creating your own workflows, but that’s beside the point being made here.) Lest we forget about Siri; being able to use your voice to activate shortcuts is a boon for people with motor delays, as the “hands free” experience can be empowering.

For disabled people, shortcuts’ focus on speed and accessibility can open up new possibilities in terms of what they can do with their iOS devices and how they do things. Throw in system accessibility features like VoiceOver and Dynamic Type, and the Shortcuts app becomes far more compelling than simply being a sheer productivity tool.

”We see huge accessibility potential with Siri Shortcuts and the Shortcuts app. It’s already making a difference — helping people across a wide range of assistive needs simplify every-day tasks like getting to work, coming home, or staying in touch with friends and family,” Sarah Herrlinger, Apple’s Senior Director of Global Accessibility Policy & Initiatives, said in a statement. “We’re getting great feedback about how powerful the technology is in streamlining frequent tasks and integrating multiple app functions with just a single voice command or tap.”

How I Use Shortcuts

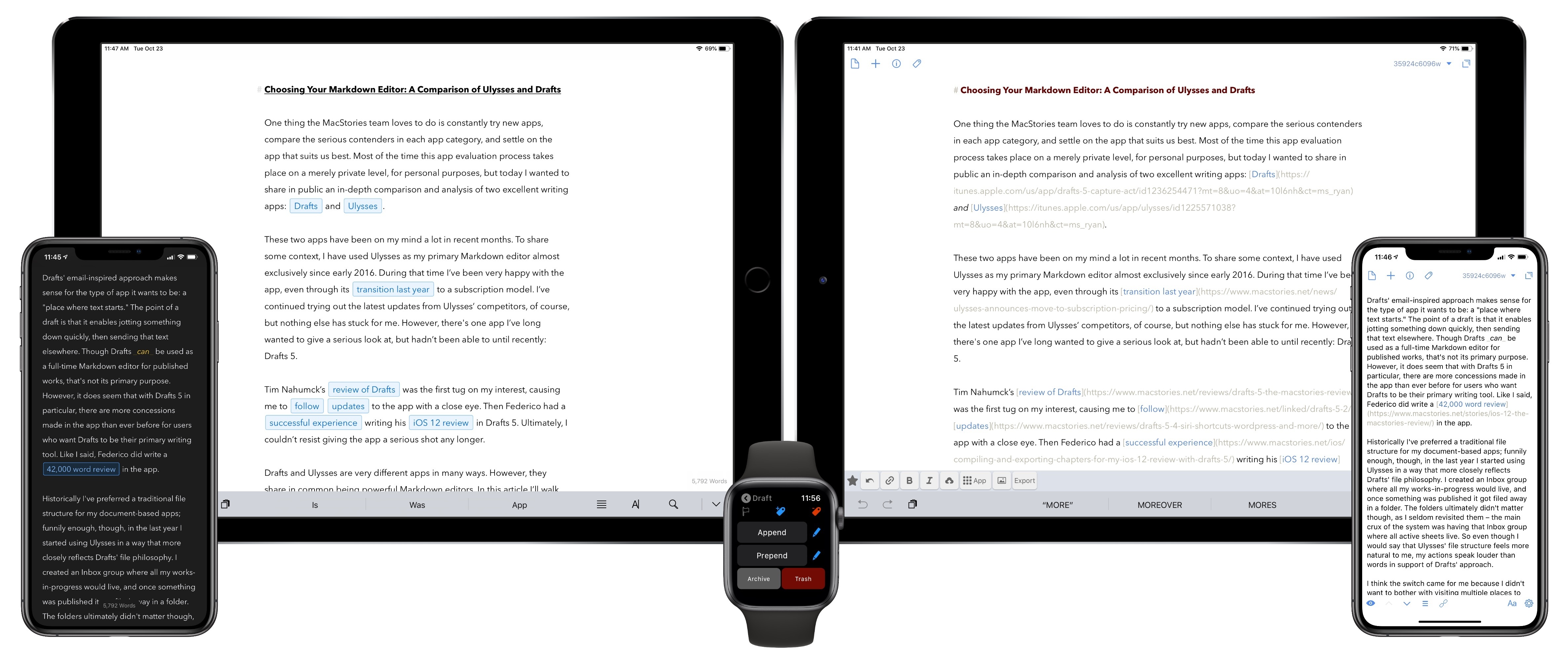

I am far less prolific in my adoption of shortcuts than some people. Others, like Federico and Matthew Cassinelli, are far more well-versed in the intricacies of what is possible and, more importantly, how you chain certain commands together.

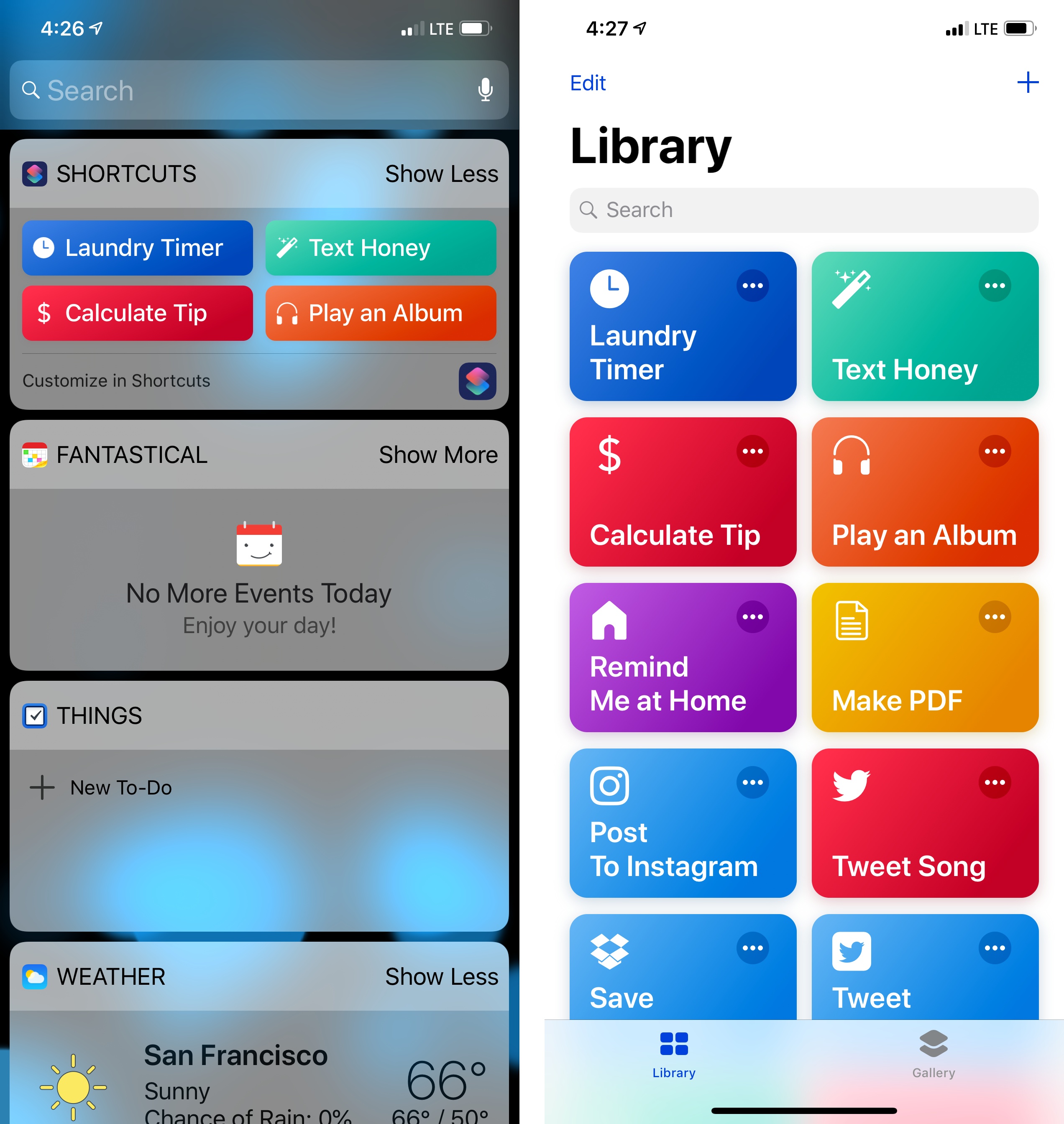

My needs for shortcuts are pretty spartan. The shortcuts I use most often are practical, everyday ones I found in the Gallery section of the app. I currently have thirteen shortcuts; of those, the ones that are the most heavily-used are the laundry timer, tip calculator, and one for texting my girlfriend. While I have enjoyed spelunking through Federico’s work for esoteric, power user shortcuts, the reality is my work doesn’t require much automation. I typically don’t need to do fancy things with images, text, and the like. That isn’t to say these tools aren’t cool or valuable; they’re just not necessarily for me. For my needs, quick access to, say, the laundry timer is worth its weight in gold because I always forget to move my clothes.

Consider another shortcut of mine, Play an Album. I’ve been listening to Eminem’s new album, Kamikaze, virtually non-stop since it came out at the end of August. Rather than manually launch the Music app, find the album in my recently played queue, and hit play, I can utilize the Shortcuts widget to play it with a single tap. The manual method is three steps which, while not tedious for me in any way, is more work. Going back to the task analysis analogy I used earlier, not only is Play an Album faster, it particularly helps me conserve precious visual energy I otherwise would have expended finding the album. For fine-motor skills, the shortcut also saves on potential cramping in my fingers caused by my cerebral palsy. Again, what can take multiple taps can be condensed into a single motion. For many, that’s a huge win.

The same concept applies to sending iMessages to my girlfriend. Using the shortcut, what would normally be a multi-step process is reduced to a single step. The advantage for me is a matter of kinetics, but for others, the advantage very well could reduce cognitive load and increase executive function. Not insignificant.

The Bottom Line

As is the case with stuff like Markdown and Apple Pay, technologies not built expressly for accessibility’s sake, the Shortcuts app is so well considered and approachable that anyone can use it, regardless of ability. There are no complicated settings or special modes; as Apple designed it, it just works as they intended it.

That’s what makes Shortcuts’ star shine brighter. Yes, Apple is pitching it for speed and convenience. Yes, shortcuts can be as pedestrian or as nerdy as you want them to be. Above all, however, the Shortcuts app is accessible. It’s an app that’s reachable to the widest possible audience, turning its utilitarianism into something far greater.