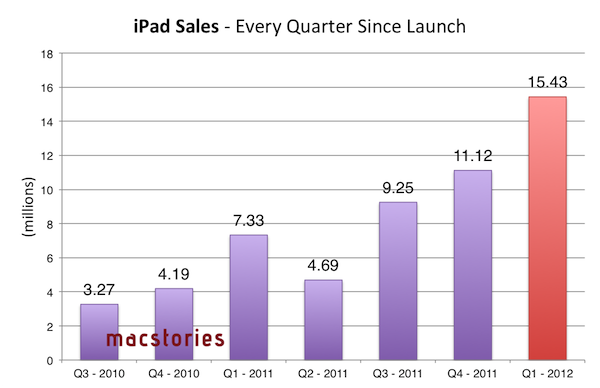

A few hours ago I listened to the latest episode of Shawn Today (a daily podcast from Shawn Blanc available to members of his site), and in it he discussed the issue of whether the iPad is a Personal Computer. This follows an article by Matthew Panzarino on The Next Web yesterday, titled “Look, tablets are PCs, get over it”. In fact I could point to quite a few articles and discussions about this question of whether tablets (specifically the iPad) are PCs. But Shawn’s episode and Matthew’s post have inspired me to also weigh in on the discussion today, with why I believe the iPad should legitimately be counted within the PC market.

I’ll just start with this question: what computer is more personal than an iPad? The tablet form factor and iOS software combine together to make using the iPad a far more personal computing device than a traditional PC desktop or laptop, where you have to interact with the software from an arm’s length away, using a mouse or trackpad and a keyboard.

So the iPad is personal device, but is it a fully functional computer? John Mello at PCWorld says no, because in his opinion people don’t use it for content creation. Matthew’s article on TNW does a great job at dismantling this oft-quoted “complaint” about the iPad and I recommend reading his entire argument. When the iPad first came out I must admit I had the same thoughts about the device, but as time has gone on I have increasingly used it for content-creation — whether it be annotating PDFs for studying, writing, and even some (very average) efforts at using iMovie. Content-creation on the iPad will continue to become more common as people adjust to the device and as app developers continue to adapt to creating great software for the iPad – just look at how productivity apps have improved and advanced in the past year on the iPad.

Sure, some content-creation tasks may never be as easy to do on an iPad compared to a more traditional PC – things like advanced video editing or long stretches of writing. But by the same token, a small netbook isn’t good for those tasks either and yet it is counted as a PC. I know I would always choose an iPad over a netbook for virtually any task because in my opinion it is a far more capable personal computer. On the flip side, I think the iPad is actually a better computer for things like annotating PDFs with apps such as PDF Expert. Then for things like advanced video or audio editing it’s only inevitable for those apps to transition to iOS, in fact just today Avid Studio was released – it may be a distilled version of the advanced desktop version, but it will evolve and become increasingly powerful for most tasks that an average user and even “pro-sumer” will need. The iPad is personal and (in my opinion) it is also a functional computing device.

So if you are excluding the iPad from the personal computer category, does that mean there is some checklist of requirements for a device to be a PC? Does it need a keyboard, or perhaps a trackpad or a mouse, or does it just have to be able to install any application you want (without the approval of a gatekeeper such as Apple)? All of these ‘requirements’ are completely arbitrary - with no practical reason as to why they are required to be on a PC. You can still connect a keyboard to the iPad if you need one for extended periods of writing, your finger is the “mouse” and Apple’s App Store has mostly protected consumers from nefarious apps or excessively useless/buggy apps – virtually everything I need is on the App Store (in fact there are over 170,000 apps just for the iPad). You may not like this policy (I can understand that, even if I don’t agree with it), but is it really a reason to bar the iPad from being counted as a PC? Again, that’s completely arbitrary.

Arbitrary: Based on random choice or personal whim, rather than any reason or system.

If you are still thinking that the iPad doesn’t count as a PC, what will all those Windows 8 computers in tablet/slate form be counted as? You can’t bar them from being “a PC” because they will be able to “morph” into what is essentially a Windows 8 laptop with a traditional Windows desktop, use a keyboard (and even mouse) and yet you can use it like them as tablets with a different, touch-based UI.

But if you do count them as a PCs, you surely have to count the iPad as a PC too then. They will be virtually identical devices from a functionality and experience point of view, unless you say the Windows 8 tablet is a PC because it will still have the traditional Windows desktop, and then I go back to the fact that it is an arbitrary requirement. One might actually argue (from what we know at the moment), that the iPad is more functional and will provide a better experience because it has two years of developer support with apps that have been specifically designed for the touch interface, whereas any Windows 8 tablet may be handicapped with the Windows desktop because it isn’t designed for touch-input and Metro may lack many apps at launch. The reality is that both should be counted as PCs: it is the only logical solution.

But…but…..but….

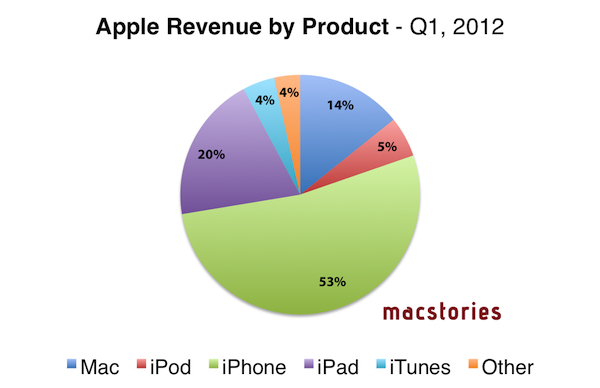

You might now point to the fact that Apple has touted the iPad as a Post-PC device, so surely if Apple themselves aren’t calling it a PC, it shouldn’t then be counted in any PC marketshare analysis. It’s a decent point, but I think Apple did that as more of a marketing move, to point out that it is a different, unique device. In fact, it is the next evolution (if not revolution) of the personal computer. Maybe the solution is just calling the “traditional” PC category something different (Desktops & Laptops perhaps?) that would make much more sense than trying to arbitrarily force the iPad out of the PC category.

One other decent rebuttal may be to then ask, if you are including the iPad, why not also include the iPhone. It’s a very good point, because I think it is also a personal computing device to some degree. I think the reason why it’s legitimate to leave the iPhone and other smartphones out of most PC market analysis is because there are enough points of differentiation between the traditional PC/iPad and the smartphone in the way it is used and experienced. These include the fact that smartphones have a distinct use case of being always-on communication devices, time management devices (Calendar/To-Do apps, etc), time-wasters (Angry Birds in a long queue, anyone?), and are occasionally used for content-creation or content consumption. They are also devices you spend using for a few minutes at a time (typically), multiple times a day — rather than PCs (including iPad), which you use for longer periods of time.

You might claim these are arbitrary reasons and, yes, to some degree they are, but that’s because the line between whether a smartphone can also be counted as a PC is a far blurrier line than that of iPads as PCs. In my opinion at least, it would be OK to include smartphones as PCs in a market analysis if there is a good reason as to why it’s an important conclusion - such as an analysis of trends. A good example of this is Horace Dediu, who included smartphones as PCs in the final graph of his article entitled “The rise and fall of personal computing”.

So as Matthew Panzarino said yesterday in a very succinct title and what I completely agree with, “tablets are PCs, get over it”.