Within the next few months, macOS Server as we know it today will be going away, with many of its services being deprecated. Things like hosting calendars, contacts, email and wikis are going away as Apple focuses the product on “management of computers, devices, and storage on your network.”

This shouldn’t come as a surprise. macOS Server has been languishing for years, with many of its most common features being integrated into the mainstream version of macOS.

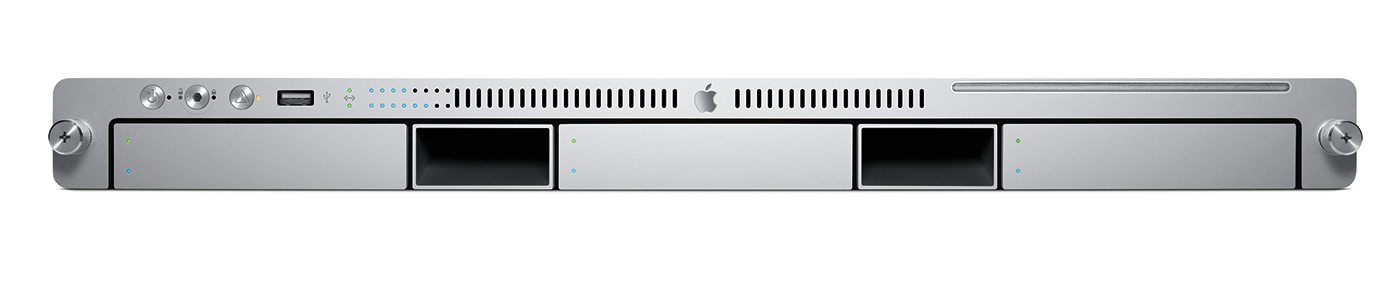

For fans of macOS Server, this just another in a long string of disappointments over the years. But none of them were as big as the cancellation of the Xserve, Apple’s rack-mountable 1U server, back in January 2011.

Running the risk of reopening old wounds, let’s look back at this unusual product and its nine year lifespan.

Xserve

The Xserve seemed a little out of left field when it was introduced back in the spring of 2002. In the 90-minute keynote, Steve Jobs and a much younger Tim Cook explained Apple’s thinking behind releasing a server that could bolt right into a rack.

The Mac was already in a lot of Fortune 500 companies, Jobs argued, but not a lot in the IT environments that ran those companies. Apple was entering the market humbly, he said, primary focusing on Mac-heavy companies and the education market.

Apple wanted to meet these needs:

- File and print services

- Hosting websites and email

- Hosting databases

- QuickTime streaming

- Computational tasks

These customers didn’t want to use a beefed-up Mac desktop, Jobs said, but rather a rack-mountable, streamlined product with a lot of flexibility in terms of storage, serviceability and remote management.

The Xserve ran Mac OS X Server, which bolted the above services (and more) to Mac OS X, which was already running on Unix, which gave IT professionals powerful tools at their fingertips. Unlike other server products, the copy of Mac OS X Server on the Xserve was the unlimited version, meaning a company didn’t have to pay Apple for additional licenses when they added additional users.

Coupled with that was a huge commitment in terms of customer service. Apple touted its integration of hardware and software being a big win in terms of service, as one vendor supplied both the Xserve’s hardware and software. Past that, the company promised 24/7 phone and email support as well as spare part kits that allowed for rapid repairs by on-site technicians.

Over the years, the Xserve hardware improved, becoming much powerful than the original G4 model introduced in 2002, but let’s start there.

Xserve G4

The original Xserve’s specs may look laughable now, but at the time, it was the most powerful Mac ever built, with dual 1 GHz G4 processors, 266 MHz DDR SDRAM, four ATA/100 hard drives, two Gigabit Ethernet ports and two PCI slots.

The low-end model, with a single 1.0 GHz processor, a 60 GB hard drive, and 256 MB of RAM was $2999, but a $3999 SKU with dual processors, 512 MB of RAM and a 60 GB was available as well. To fill up those additional drive slots across the front, customers could attach Ultra ATA/100 7200rpm drives to the custom drive sleds and slot them into place.1

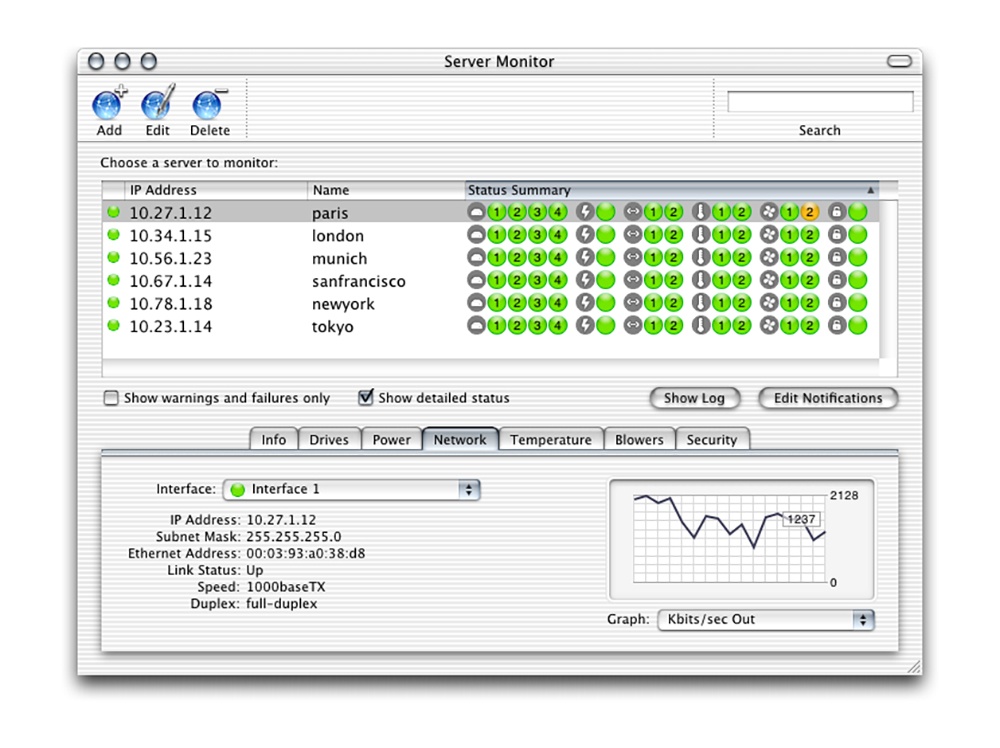

To manage this hardware, Apple introduced a new application named Server Monitor, as explained on its website:

Xserve also features Server Monitor, a remote monitoring application that lets you administer your servers — on a machine-by-machine basis, or hundreds of machines at a time — with an intuitive, easy-to-use Aqua interface. You can gauge everything from system temperature, blower operation, hard drive health and Ethernet status to the condition of your power supply. Red, yellow and green lights provide a quick visual summary of hardware health, and a tabbed window interface gives you one-click access to the details of each hardware subsystem.

Just look at all those pinstripes:

Apple iterated quickly on its original hardware. Seven months in, it revved the Xserve to include 1.33 GHz G4 processors and a slot-loading optical drive.

A month later, Apple unveiled the Xserve (Cluster Node), a model with only one hard drive, no optical drive and no graphics card. This model was designed to prioritize computational tasks. It was priced at $2,799 for a dual 1.33 GHz G4 system – the same price as the entry-level single processor Xserve.

Xserve G5

At Macworld 2004, an hour before announcing the iPod mini, Steve Jobs introduced the Xserve G5. Cramming up to dual 2.0 GHz PowerPC G5 chips in a system just 1.75 inches tall required a complete redesign of the case. Apple had to sacrifice one of system’s hard drive bays to make fan for two new air intakes:

In addition to the new silicon, the Xserve G5 shipped with EEC RAM, a first for any Apple hardware. It moved to SATA drives, but retained the clever hot swappable chassis design from the G4.

Also like the G4, the copy of Mac OS X Server that came with the Xserve G5 included unlimited licenses and remote management tools.

Apple sold three flavors of Xserve G5: a $2,999 single-processor model, a $3,999 dual-processor model and a Cluster Node model with Dual G5s but only one hard drive bay for $2,999.

The Xserve G5 saw one update, in January 2005, with processor speeds up to 2.3 GHz, twice the RAM ceiling and support for up to 1.2 TB of storage space internally.

Xserve (Intel)

In August 2006, the Xserve made the transition to Intel processors. The new server was built using 64-bit Xeon processors, clocked up to 3 GHz. This new Xserve was up to five times faster than the outgoing G5 model, and started at $2,999. The Cluster Node SKU was quietly killed.

While the Xeons were shockingly faster than the G5s, they also ran much cooler. This gave Apple the space to add redundant power supplies to the Xserve for the first time and increase the internal storage to 2.5 TB.

With this generation, Apple made the machine far more customizable than ever before. BTO options included a Dual-Layer SuperDrive, 32 GB of RAM and the new Xserve RAID card. This card let users keep the internal drives in a RAID configuration, downplaying the need for external RAID products. Other PCI Express cards could be installed to support Fibre Channels, Dual-Channel Gigabit and more.

In early 2008, Apple revised the machine, increasing the base processor speed to 2.8 GHz, improving the built-in GPU and swapping the FireWire 400 port on the front of the product to a USB port.

In April 2009, the Xserve moved to a new generation of Xeons, boasting twice the performance of the previous model, despite offering slightly lower clock speeds than before. Memory access was increased from 32 GB to 48 GB, and customers could order their Xserve with an optional 128 GB SSD boot drive, freeing up the three spinning hard drives to be dedicated completely to storage.

Xserve RAID

The Xserve had a companion product, named the Xserve RAID. The first model shipped in early 2003, after being previewed with the original Xserve in May 2002.

It was a rack-mountable storage solution that supported 14 180 GB drive modules, each on a separate ATA-100 bus. Like the Xserve, the Xserve RAID drives mounted across the front of the device. I think it’s one of the prettiest pieces of hardware to come out of Apple in the early 2000s:

The Xserve RAID isn’t as deep as the Xserve, but at 3U (about 5.25 inches) in height and weighing in at nearly 100 pounds when filled with hard drives, it is a solid piece of hardware.

To connect to the Xserve, the Xserve RAID supported dual 2 Gb Fibre Channels. That meant the two machines could talk to each other at speeds up to 400 MBps.

From the beginning, the Xserve RAID had redundant power and cooling systems, something that wouldn’t come to the server for several revisions.

In January and October 2004, Apple updated the product, allowing for greater storage capacity. By the end, it supported up to 5.6 TB worth of data.

On the software side, Apple added support for Linux and Windows clients, meaning you didn’t have to hook up an Xserve to take advantage of the Xserve RAID.

Fully loaded, you could spend $12,999 on an Xserve RAID. While that may seem like a lot, it was noticeably cheaper than some competing products. For instance, in 2004, the price per GB for the Xserve RAID was $3.14, while Dell came in at $9.05 and HP at $11.39, according to Apple.

The Xserve RAID was discontinued in February 2008 after going over three years without an update, as reported by Jim Dalrymple at the time:

Apple struck a deal with Promise Technology to have its RAID systems qualified for use with Xsan 2,2 so users are not left out in the cold. Apple said the Promise product delivers on the features its customers have been asking for and it also delivers significantly greater performance.

“We decided to focus our efforts where we could add most value, with Xserve, Xsan and Leopard Server,” Apple spokesman Anuj Nayar, told Macworld.

Customers that already own an Xserve RAID will still be able to add Apple storage too. While the RAID system itself has been discontinued, the company will still sell modules for it.

Post-Xserve Life

The Xserve itself followed in the RAID’s footsteps in January 2011. When the company announced the product, it said users weren’t content with running a desktop Mac as a server, but that’s exactly what Apple suggested they do in its Xserve Transition Guide. Apple had been shipping a Mac mini with Snow Leopard Server since the fall of 2009, and said it was the most popular server system it sold. A Mac Pro configured with Server was on sale as well, but proved less popular.

I was in IT at the time the Xserve’s demise was announced, and rushed to order one. For the needs my company had at the time, it was by far the best option. I know many IT professionals were upset to see the server go away, but I think most migrated to a collection of Mac minis to run Mac OS X Server, coupled with external RAIDs.

At the time, it felt like having the rug pulled out from under us, but in hindsight, it should have probably been more obvious that the Xserve’s end was coming. Most people just didn’t need the horsepower the machine offered, and I can’t imagine it ever sold all that well, even at its peak.

Now macOS Server itself is next on the chopping block, at least for many users. The reality is Apple is a company focused on the consumer and professional markets, and isn’t interested in making a big dent in the IT market. That’s a bit of a bummer for this nerd, but I understand it.