MacPaw, makers of CleanMyMac, Gemini, and other apps, launched a public beta subscription service of hand-picked Mac apps last December called Setapp. Today the service, which aims to become the ‘Netflix of apps,’ was officially launched with a stable of 61 Mac apps.

For a flat subscription fee of $9.99 per month, customers can download any of the 61 apps and use them as long as they continue to make monthly payments. After MacPaw receives a 30% cut of customers’ subscription fees, developers who participate in Setapp are paid based on a formula that accounts for the price their apps are sold for outside the service and whether customers use the apps each month, which MacPaw tracks.

Getting started with Setapp is easy. After signing up and installing Setapp, a new folder appears in the Finder on your Mac called ‘Setapp.’ Setapp also resides in your menu bar and optionally as a folder in the Dock.

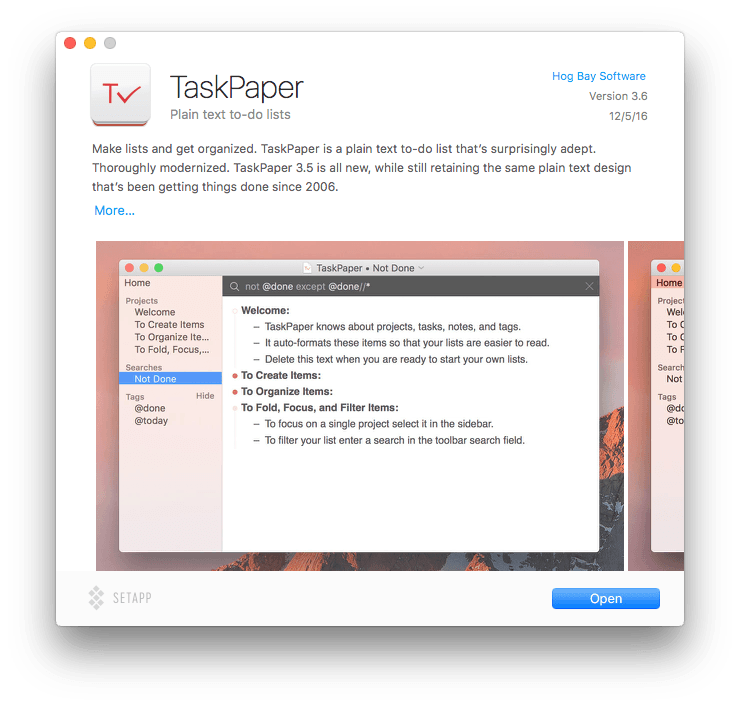

If you look in the Setapp folder in Finder, you will see icons for all 61 apps. Each icon has a little downward pointing arrow to indicate that it hasn’t been installed yet. Double clicking the icon opens a description of the app with screenshots similar to what you find on the Mac App Store. The app is installed when you click the ‘Open’ button from an app’s overview window.

Setapp should be a bargain for anyone interested in several of the apps it offers, especially the ones that cost the most outside Setapp. Although it is difficult to anticipate the cost of purchasing and updating apps over the course of a year or more, the subscription approach makes economic sense for users in those circumstances and is worth considering.

The benefits of Setapp to developers are less clear. If Setapp attracts large numbers of new users to the apps in its service, some developers’ apps could thrive, but that is by no means a given. To try to get a better sense of what has attracted developers to Setapp, I asked a couple who are participating in Setapp how they feel Setapp fits with the other sales channels for their apps.

Luc Vandal, creator of Screens, a MacStories favorite for screen sharing, said:

Setapp is just another way to have our apps available to a different set of customers. For instance, we offer Screens directly from our store, on the Mac App Store and now on Setapp. This way, we ensure that we reach users seeking different ways to buy apps.

I also corresponded with Marcus Fehn, one of the co-founders of The Soulmen, makers of Ulysses, a beloved text editor used by many of us at MacStories, who also sees Setapp as additive to his company’s other sales channels:

Ulysses for iOS will always be distributed via the App Store anyway, and our main channel for the Mac app will remain the Mac App Store. We are seeing Setapp as sort of a “special interest bundle” – it’s not so much about a new channel of distribution, as it is about giving users access to our app as part of this bundle.

Finally, Brett Terpstra, creator of Marked, a Markdown previewer for macOS had this to say on his site when the Setapp beta launched:

What clinched my decision to include Marked 2 in Setapp is the fact that I can still sell directly and via the Mac App Store. So I’m hoping to get sustainable, subscription-based revenue, without having to eliminate my current purchase options.

If Setapp helps developers build sustainable businesses by attracting new users, I’m all for it, but I’m skeptical. There’s a tension here. Customers are being offered an all-you-can-eat buffet of apps. The more apps that are used, the better the value for customers. At the same time, the more apps a customer uses, the less each developer of those apps gets paid. That might be fine if these are customers the developers wouldn’t attract without Setapp, but what if each Setapp user means one less full price app sale?

I can’t shake the feeling that Setapp may be a symptom of, and not a cure for, the intense financial pressures that indie developers face today, even developers with highly-regarded apps. Time will tell, and I hope I’m wrong, but Setapp feels like a short-term solution to a long-term problem that I’m afraid will hurt developers in the end by driving average app prices down even further. And what’s bad for developers in the long run, ultimately hurts users too.