All the Rest

QuickTime

As I covered at the outset of this review, the release of Catalina completes Apple’s multi-year transition from 32- to 64-bit apps. That means the end of the line for apps like QuickTime Player 7, which some people still used for its support of older file formats after QuickTime Player X was released. Although Apple isn’t bringing back Flash video playback, the latest update to QuickTime provides some nice enhancements.

My favorite convenience is the addition of a Picture in Picture button next to the playback controls. It works just like the similar button you’ll find in videos in Safari. Click the PiP button and drag the resizable video window into a corner to watch as you do something else. The window will float above the other windows on your screen. When you’re finished, just click the PiP button again to return it to the app’s main window.

QuickTime has regained QuickTime 7 Pro’s ability to build a video from sequentially numbered still images too. After picking a frame rate, resolution, and encoding quality, you can save the resulting video as an H.264, HEVC, or ProRes video file. One common use for the feature is creating time-lapse movies from a series of photographs taken at regular intervals.

Also, QuickTime’s Inspector has been beefed up with additional information like the color space, aspect ratio, scale, and other data. QuickTime adds alpha channel transparency support and displays timecodes if they’re embedded in a video too.

Home

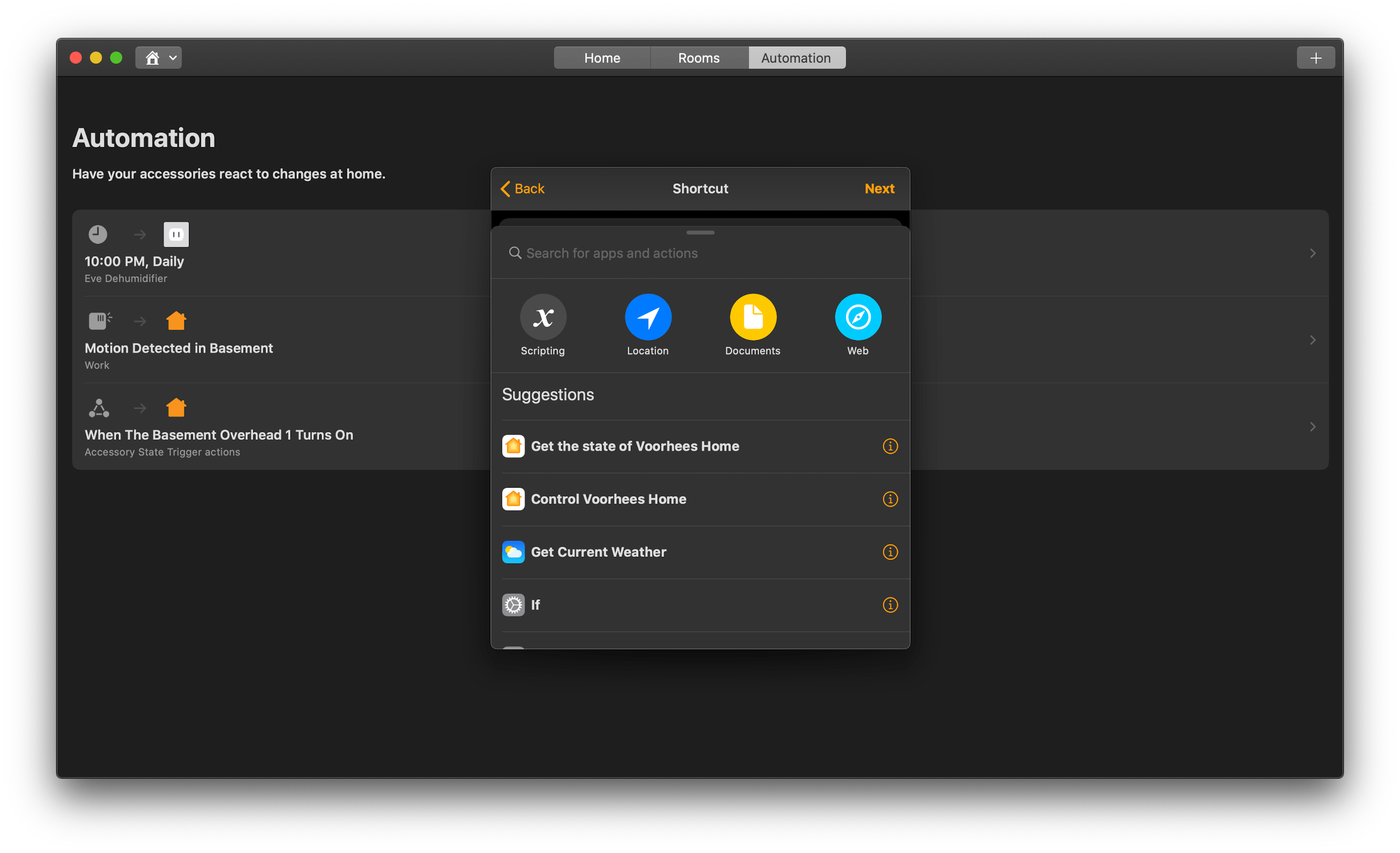

Just like Home on iOS and iPadOS, the Mac version has added a limited set of Shortcuts actions that can be built into HomeKit automations. The actions available and opportunities they present for the creation of more robust automations in the Home app is exciting. For the details of what is and isn’t possible with Home-based automations, check out Federico’s iOS and iPadOS 13 review, which covers the options in depth. Because the two platforms essentially work the same way, I won’t retread the same ground here.

Just as on iOS and iPadOS, when you get to the step of picking accessories and scenes to add to an automation, there is an option at the bottom of the window to convert the automation to a shortcut. What’s remarkable about that and noteworthy compared to iOS and iPadOS is that unlike those OSes, there is no Shortcuts app on the Mac. Granted, the actions available in Home are a small subset of everything that’s available in the iOS and iPadOS app, but I expect this is just the start.

A unifying theme of Catalina is a rationalization of each platform’s apps and functionality so as to provide a more unified experience on every platform. For instance, why should finding your devices or friends and family involve two apps on iOS devices but only the web on the Mac? There may be perfectly valid historical reasons why that functionality ended up that way, but with Catalina and its other OSes, Apple is taking steps to bring them closer together than ever, and right here in Home, the future of automation on the Mac is hiding in plain sight.

I don’t expect we’ll see AppleScript or Automator go away soon, but I do expect Shortcuts to expand onto the Mac and benefit from the built-in community of users who are building and sharing shortcuts on iOS and iPadOS. It’s that unification of experience where skills learned on one platform are transferrable to the other that will enable the biggest user experience leaps in the years to come.

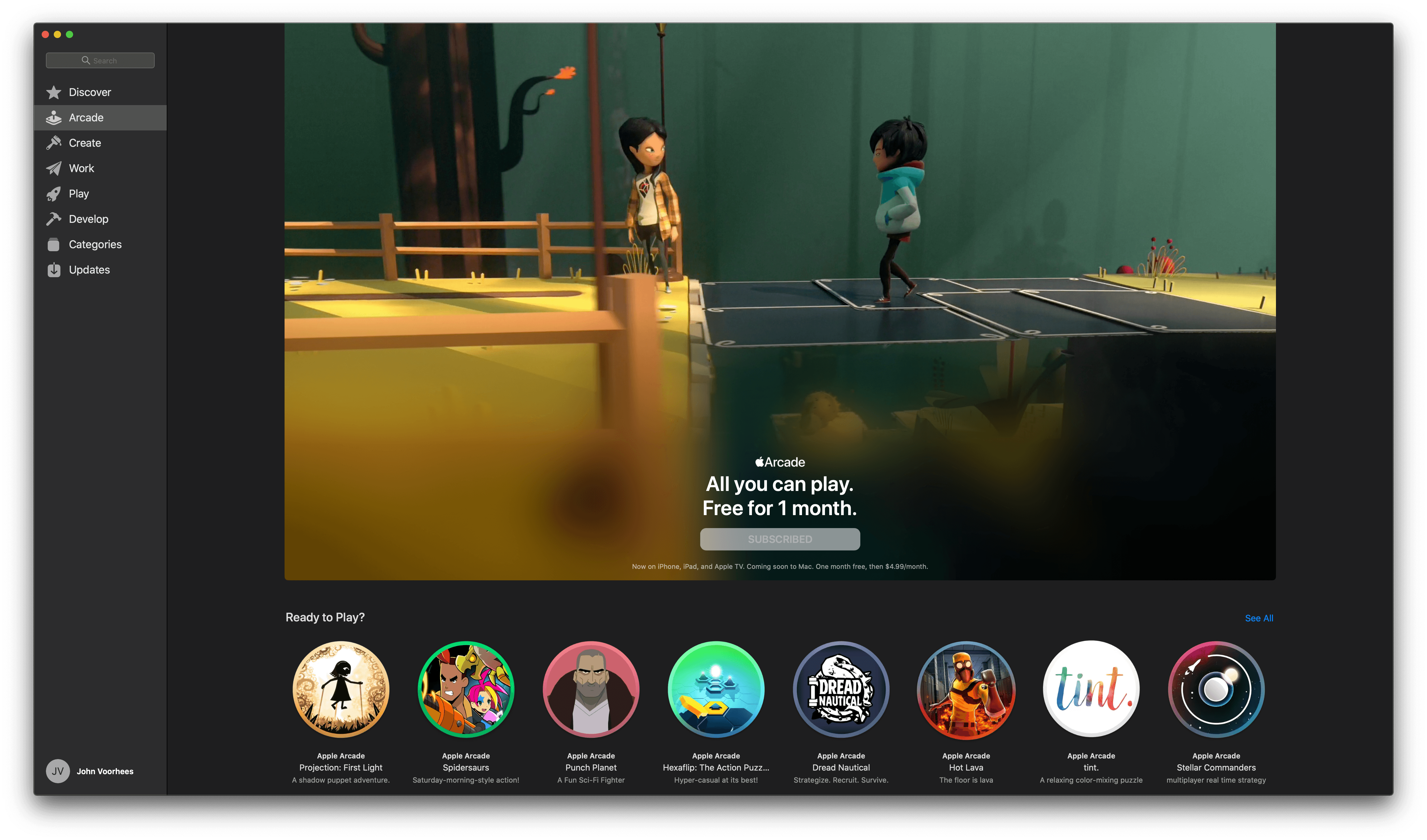

Mac App Store

The Mac App Store has remained largely unchanged from Mojave, except for the addition of an Apple Arcade tab in the sidebar and moving password requirement settings to the Apple ID section of System Preferences. As with iOS and iPadOS, Arcade soft-launched to beta testers shortly after the GM build of Catalina was released. It’s too early to judge Arcade on the Mac, but as of its release to the public, fewer than half of the games released on iOS and iPadOS are available on the Mac, and the Store’s tab has no editorial content, except for a couple of short articles promoting the Arcade service itself. However, based on how quickly the Arcade tab has been filled on iOS and iPadOS, I expect that will change soon on the Mac too.

Conclusion

There’s no greater threat to the Mac than resistance to change that exists not because the change is worse, but because it’s different. For years there have been complaints that iTunes was a creaky, buggy mess and that the app ecosystem on the Mac was stagnant. Now that Apple is breaking up iTunes and bringing iPad developers to the Mac, that’s shifted to nostalgia for iTunes features not in Music and declarations that there are plenty of good apps for the Mac already. Perhaps that’s just human nature, but it’s not the way to preserve the Mac’s relevancy. It’s how Microsoft got itself into a cycle of preserving old versions of Windows for so long that it stifled innovation on the platform.

Catalina is a cold splash of water in the face of users accustomed to small incremental changes to macOS in recent years. What makes Catalina different from updates in years past is Apple’s renewed commitment to the Mac.

In 2017, Apple held an unprecedented meeting with a small group of writers to lay out its roadmap for the Mac. The meeting signaled more than a preview of the Mac Pro that is still in development. The company was proclaiming a new strategy for the Mac, though in typical Apple fashion, without spelling out the exact details.

Catalina is the first sign of the software side of that strategy. Unlike hardware though, the OS has a much more direct effect on the way you use your current Mac, which makes the transition more fraught with risk. There are certainly rough edges and parts of Catalina that feel unfinished, but it would be unfair to judge the macOS update as though it were the destination itself. We’re only in the first year of a multi-year process. From that perspective, I’m encouraged.

Catalina is a careful balancing act between the old and new. One of the most successful advances by Catalina is the breakup of iTunes. I expected far more of the legacy features to be shed from the app than actually were. If you’re a fan of the column browser, you may not agree with that assessment, but the fact that you can still rip and burn CDs, buy music from the iTunes Store, use star ratings, view checkboxes in the Songs list, and create Genius playlists were all surprises to me. Those features are de-emphasized and will likely fade away over time, but Catalina accommodates users who rely on them. Given the long history of iTunes and its feature set, phasing out legacy features slowly makes sense.

Less successful is Catalyst. I’ve had high hopes for Catalyst since it was previewed at WWDC in 2018. The realization over this summer that Apple wasn’t going to update its original four Catalyst apps was a big disappointment, as was the lack of documentation and sample code and the inability of developers to bundle Mac apps with iOS and iPadOS apps. Together with the workload imposed on developers by changes to iOS and iPadOS 13, many I’ve spoken to put their Catalyst plans on hold, which is understandable. That’s not encouraging because, in the short-term, it means we’re unlikely to see many of the sort of new ideas and competition that the Mac app ecosystem needs to be sustainable long-term.

Nonetheless, I’m encouraged by the handful of Catalyst apps I’ve tried. Apps like PDF Viewer, GoodNotes, LookUp, CARROT Weather, and HabitMinder should serve as a roadmap for other developers. Apple’s Podcasts and Find My apps are also better examples of what can be done with Catalyst than Home, Voice Memos, News, or Stocks. Hopefully, it’s just a matter of time before the company rethinks some of the choices made in its early Catalyst apps.

What’s just as clear about Catalina, though, is that the transformation of macOS isn’t about breaking up one app or bringing iPad apps to the Mac. Catalina is more about bringing the user experiences between the Mac and other Apple platforms together. It encompasses everything from aligning the features between apps that exist on each platform, to each system borrowing interaction models from the others, but adapted to respect the differences between them – whether that’s something like the ellipsis menu buttons added all over macOS or the context menus added to iOS and iPadOS 13. The cross-pollination of macOS with iOS and iPadOS isn’t complete, and it certainly isn’t consistent in places, but it is nonetheless important because it’s what will make the Mac fit better on Apple’s computing continuum. Catalina makes the Mac a more familiar and inviting environment for the millions of iOS and iPadOS users who have never used a Mac.

That’s a hard reality to face if you are a long-time user of the Mac for whom iOS and iPadOS are the newcomers, but in the final analysis, it’s simple math. In an increasingly mobile computing-based world, the Mac’s future lies in making it a platform that has something to offer iOS and iPadOS users, and makes moving from those platforms to the Mac simple.

Perhaps Catalina isn’t such an ironic name after all. The work to fully integrate macOS into an unbroken computing continuum is far from complete. The Mac isn’t disappearing anytime soon, but it risks becoming a niche product that doesn’t get the attention that Mac users want or that I think it deserves. There’s a place for the Mac in Apple’s lineup, but the platform needs to change with the times, and Catalina is the first step of bridging the gap to its future.