Yesterday, the US Supreme Court told Epic Games and Apple, “No, thank you,” and Apple served up an ugly alert to developers who can now offer payment options outside the App Store. If you’re thinking, “Wait, didn’t this all get resolved ages ago?” I feel you. The legal system moves at its own pace, which is an order of magnitude slower than technology. However, what might feel like a lifetime ago to many MacStories readers is pretty typical. It also means that it’s time to put on my ‘former lawyer’ hat for a moment to revisit where things stand with Epic and Apple and consider what’s next.

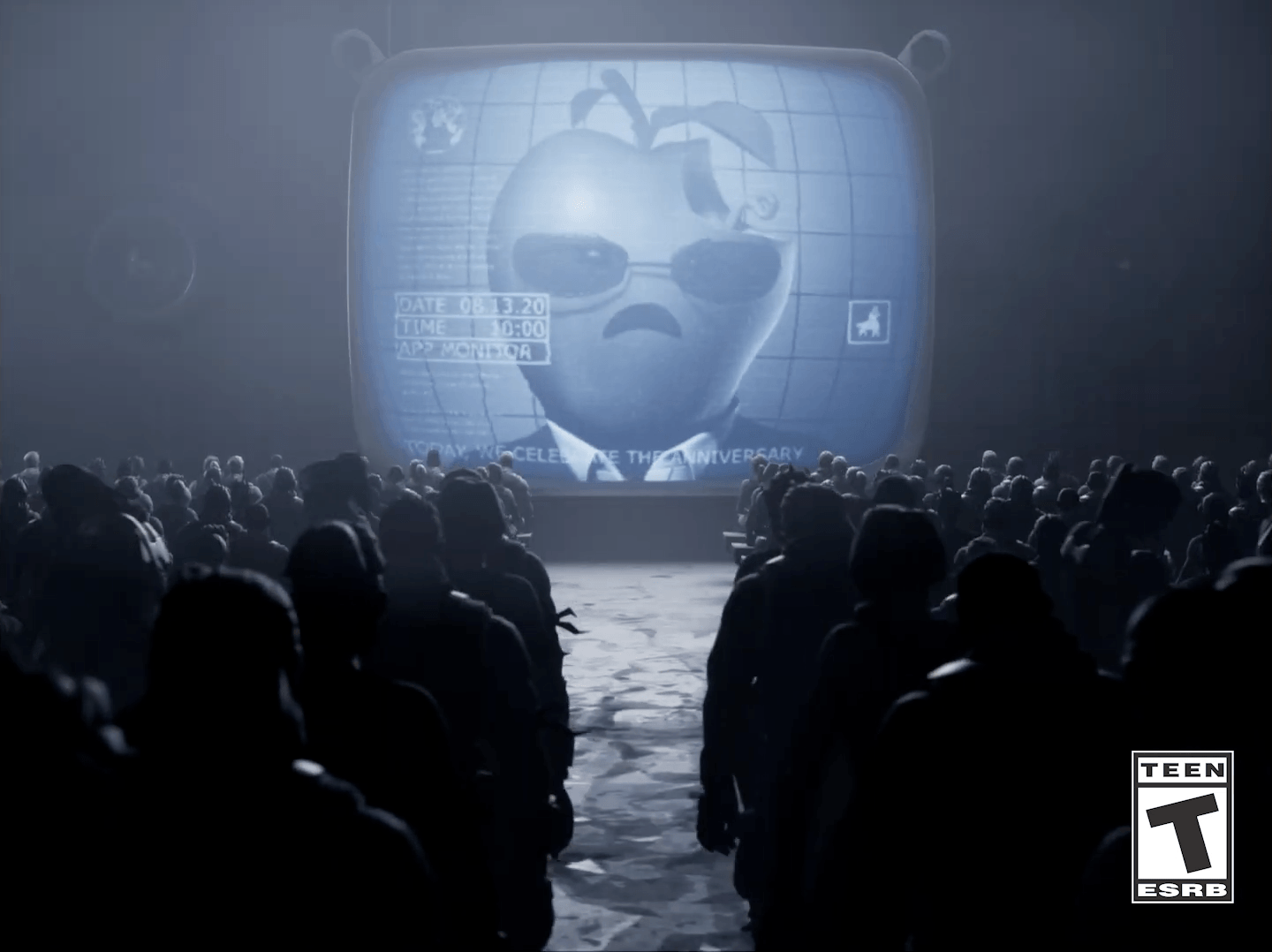

This whole mess started in the depths of the COVID-19 pandemic when Epic Games decided to manufacture a dispute with Apple by sneaking a store for purchasing Fortnite in-game currency into the mobile versions of that game. Apple removed Fortnite from the App Store, Epic sued, claiming antitrust violations, Apple countersued for violations of its developer agreements, and the rest has unfolded over the course of over three years.

The case was tried in the US District Court for the Northern District of California by Judge Yvonne Gonzalez Rogers. She decided the case about a year later, ruling that Apple wasn’t a monopoly but used a California state anti-steering law that gives judges wide latitude to fashion remedies to order that Apple cannot prevent developers from linking to external payment options in their apps. As a result, neither party was totally happy with the ruling, although Apple clearly came out of the trial with a bigger win than Epic did.

Epic’s Tim Sweeney vowed to appeal, which he did, as did Apple. As I said at the time:

I doubt Epic will prevail on appeal. Antitrust cases turn first and foremost on the trial court’s determination of the facts, and in an appeal, the trial judge’s findings of fact are given more deference than their legal conclusions. That’s because the trial judge was in the room with witnesses and, therefore, is assumed to be the best arbiter of what the evidence at trial demonstrated.

Judge Gonzalez Rodgers is no dummy. She knew there would be an appeal and crafted a decision designed to be as bullet-proof as possible on appeal.

As I expected at the time, the judge’s decision withstood both parties’ appeals. Earlier this year, the US Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit upheld the lower court’s decision, which set the stage for the US Supreme Court’s actions yesterday.

Appealing to the US Supreme Court is a little different than the initial appeal of Judge Gonzalez Rodgers’ decision because the Supreme Court doesn’t have to accept the appeal. In fact, the vast majority of appeals to the Supreme Court are rejected. When that happens, the decisions of the courts below it stand, and the decision of the trial court becomes final.

That’s what happened here. Epic and Apple were both unhappy with Judge Gonzalez Rodgers’ decision. So both appealed, the Ninth Circuit upheld the lower court’s decision, and the Supreme Court effectively said, “Go away. Don’t bother us with this.”

That’s not the same as the Supreme Court ruling against either party, as I’ve seen reported in some places. In fact, it’s the opposite of a ruling. The Supreme Court decided not to decide. That’s significant because it carries no weight as legal precedent. Had the Supreme Court ruled, the decision would have been binding on all other US federal courts. As it stands, the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals’ decision is binding precedent for the federal courts in that district only. That’s it. Parties can argue about the issues decided by the District Court and the Ninth Circuit in other districts, but they aren’t binding on those courts.

So it’s over, right? Well, sort of. Judge Gonzalez Rodgers can sleep well knowing her decision won’t be second-guessed, but as we’ve already seen from the aftermath of the Supreme Court’s non-decision, legal battles between big companies that don’t like each other and have a lot of money never really end.

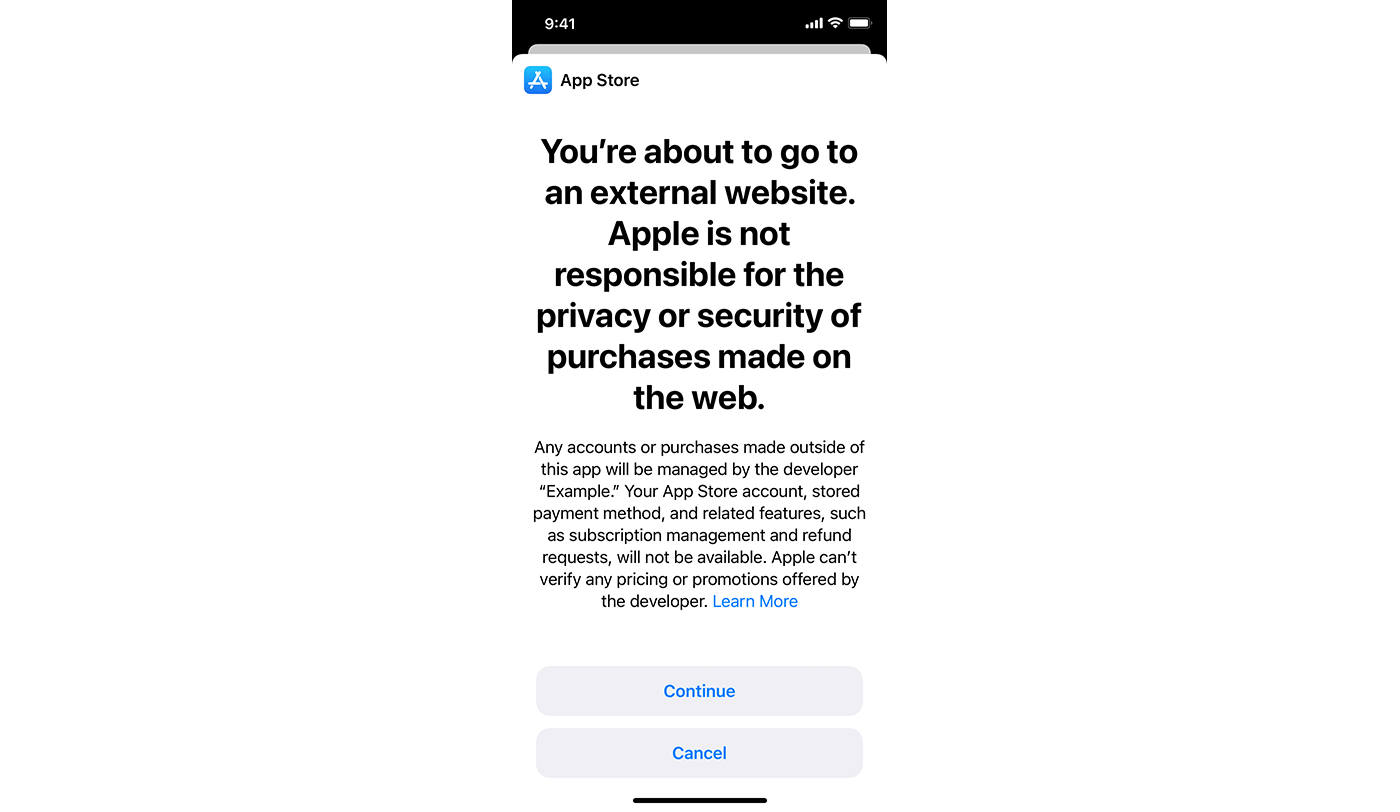

Epic’s Tim Sweeney immediately proclaimed that Epic Games would contest Apple’s “bad-faith compliance plan.” Epic can do that because all Judge Gonzalez Rodgers decided was that Apple had violated California’s anti-steering law. Apple has responded by revising its app distribution rules. Developers have to request a StoreKit External Purchase Link Entitlement and use a somewhat scary and unsightly disclosure sheet warning users of the risks of buying things on the Internet. Going this route will only save developers 3% on Apple’s App Store commission, which I expect won’t be enough for many developers to bother with. Epic and Sweeney have additional issues with Apple’s implementation, which Sweeney detailed in a statement to 9to5Mac. So now, the fight is over whether what Apple has done is sufficient to steer clear of California’s anti-steering law.

For its part, Apple says Epic owes it $73 million in legal fees it spent fighting with Epic. I have no doubt that Apple’s developer agreements provide for this sort of reimbursement and that Epic will fight it.

So, what have we learned from the past few years? The main takeaway is that it’s clear that Apple isn’t going to change the way it runs the App Store without a legal fight or government regulation. Its strategy is to fight and lobby, make incremental changes at the margin, rinse, and repeat. I expect we’ll see something similar play out with side-loading by March 7th, which is the deadline for Apple and other companies to comply with the EU’s Digital Markets Act.