Earlier this week, Apple announced a series of new accessibility features coming to its OSes later this year. There was a lot announced, and it can sometimes be hard to understand how features translate into real-world benefits to users.

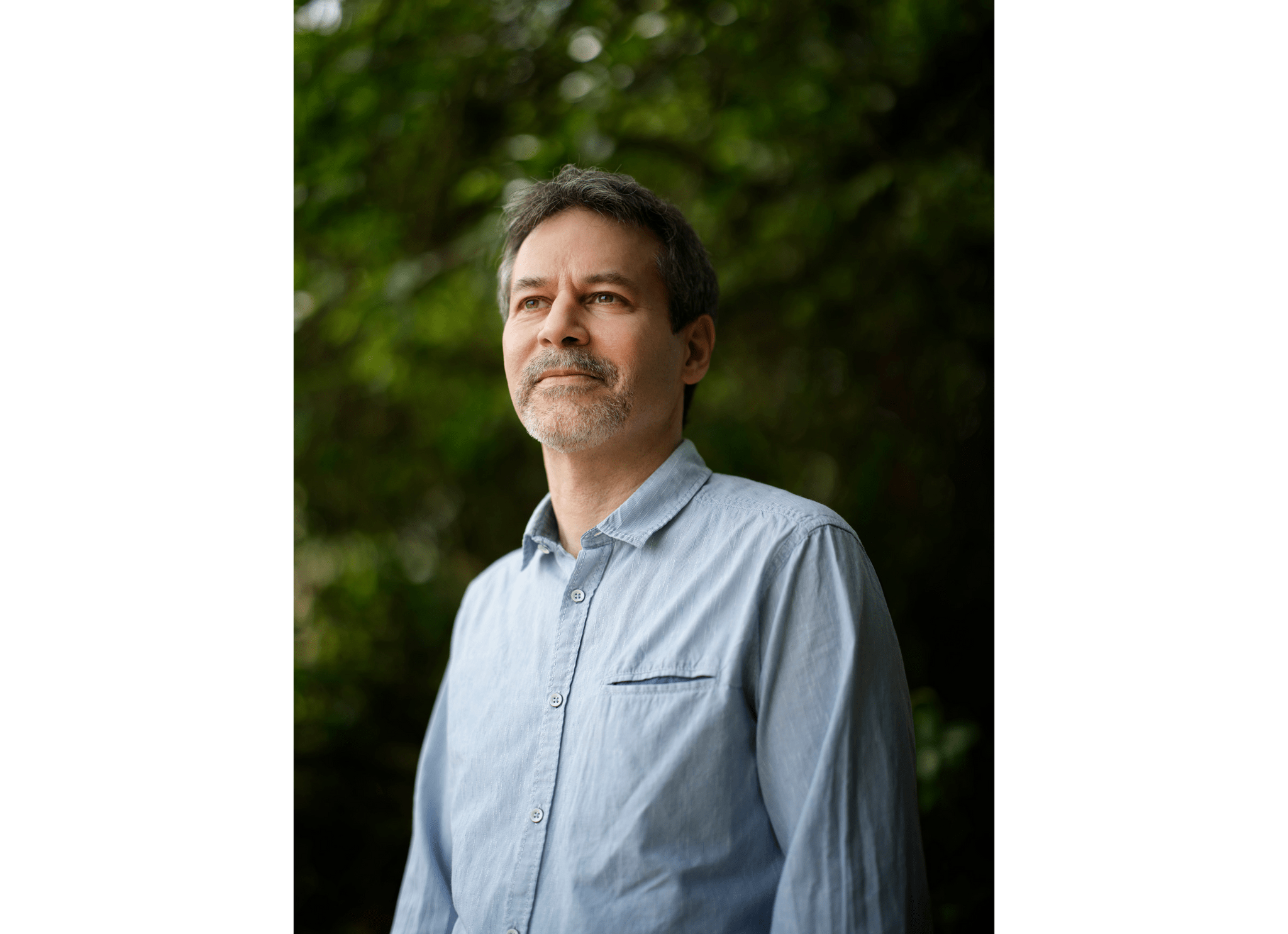

To get a better sense of what some of this week’s announcements mean, I spoke to David Niemeijer, the founder and CEO of AssistiveWare, an Amsterdam-based company that makes augmentative and alternative communication (AAC) apps for the iPhone and iPad, including Proloquo, Proloquo2Go, and Proloquo4Text. Each app addresses different needs, but what they all have in common is helping people who have difficulty expressing themselves verbally.

What follows is a lightly edited version of our conversation.

Let me start by asking you a little bit about AAC apps as a category because I’m sure we have readers who don’t know what they do and what augmented and alternative communication apps are.

David Niemeijer: So, AAC is really about all ways of communication that do not involve speech. It includes body gestures, it includes things like signing, it includes texting, but in the context of apps, we typically think more about the high-tech kind of solutions that use the technology, but all those other things are also what’s considered AAC because they augment or they are an alternative for speech. These technologies and these practices are used by people who either physically can’t speak or can’t speak in a way that people understand them or that have other reasons why speech is difficult for them.

For example, what we see is that a lot of autistic people is they find speech extremely exhausting. So in many cases, they can speak, but there are many situations where they’d rather not speak because it drains their energy or where, because of, let’s say, anxiety or stress, speech is one of the first functions that drops, and then they can use AAC.

We also see it used by people with cerebral palsy, where it’s actually the muscles that create a challenge. [AAC apps] are used by people who have had a stroke where the brain system that finds the right words and then sends the signals to the muscles is not functioning correctly. So there are many, many reasons. Roughly about 2% of the world population cannot make themselves understood with their own voice.

What’s the history behind AssistiveWare’s apps?

Niemeijer: Well, we actually got started in 2000, but at that time, our focus was on computer access technology for the Mac, helping people with physical impairments who couldn’t access their computers. That’s how we originally started. But 2009 is when we first released Proloquo2Go on iOS, but we already had an app called Proloquo on Mac since 2005, which was also in the same category.

Could you tell me a little bit more about your apps? What do they do, and how do they address some of these challenges?

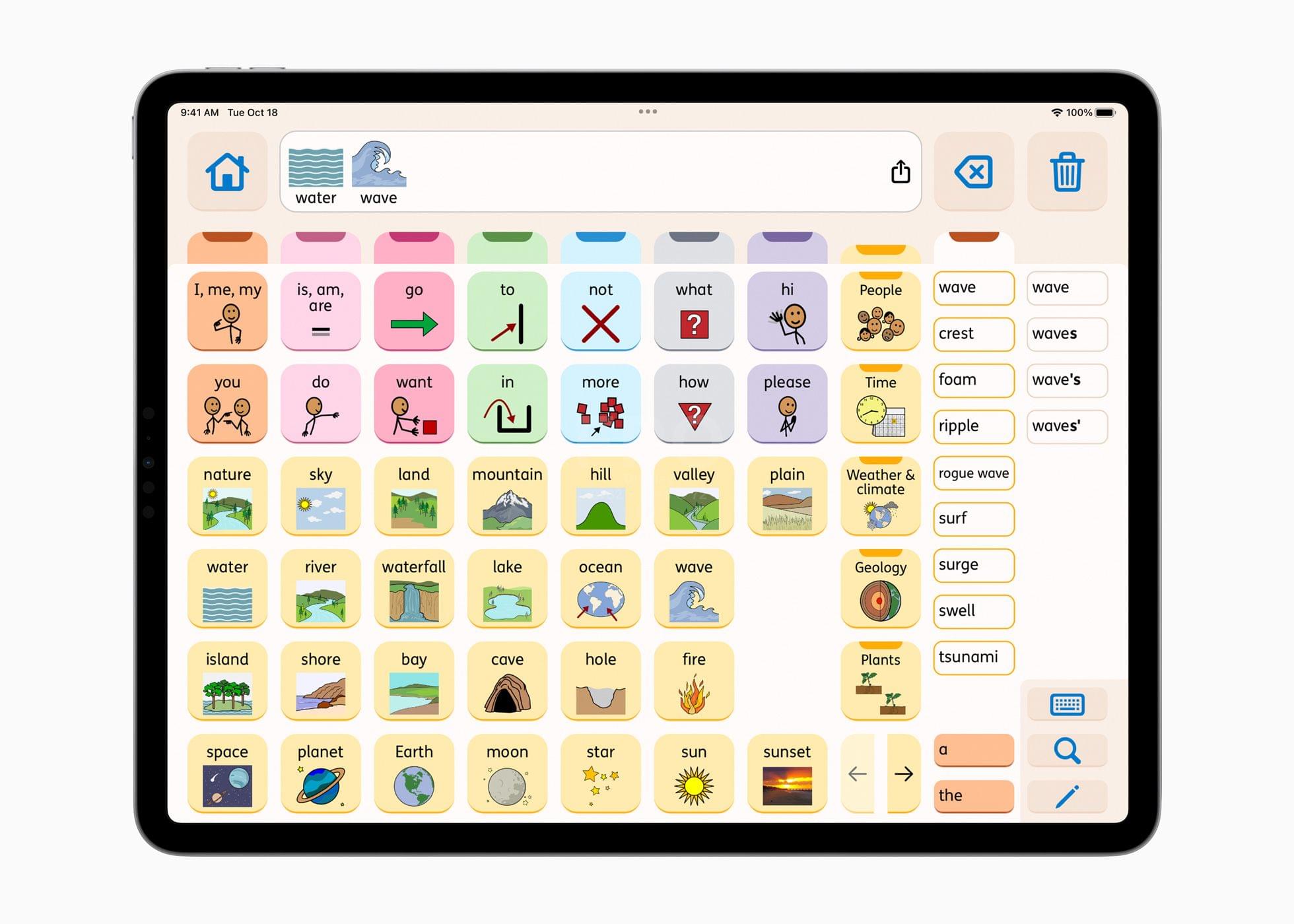

Niemeijer: So, I would say we have two types of apps. We have an app that is for people who don’t speak and do read and write, and that’s called Proloquo4Text. And then we have several apps that are designed for people who do not read and write but need speech but that are symbol supported. So they allow people who can’t read to still learn and compose messages. And they’re also designed in such a way that they help you with learning language and learning or growing towards using the alphabet. And those apps are used especially by children but sometimes also by people with brain damage. And again also, autistic people may be fully literate, but when there’s too much going on at the same time, they might find it super helpful to actually see buttons with words there rather than having to construct them letter by letter.

What excites you about the accessibility features Apple announced this week, and where do you see your apps adopting the new technologies?

Niemeijer: There’s a lot of exciting news, but I think there are two areas that are most exciting. The first is Personal Voice. There have been technologies like this on the market for a while, but there are some challenges in using them.

One challenge is that [existing technologies] typically require high-quality headsets for recording, not like Personal Voice that lets you just grab your iPhone and start.

The other part is that because of the costs involved, people often need to apply for funding, and those two things actually pose significant barriers. And where people are going to lose their voice, they need a certain amount of time to come to grips with that idea. If there are then additional barriers that prevent them from starting to record their own voice, what often happens is that they start too late and that they start doing this by the time they’re starting to lose their voice already, which means that the quality of the recordings is going to be a lot lower.

And I think the whole concept of Personal Voice, the ease with which you can make the recording, the fact that you don’t have to either look for funding or spend money on it, it takes away those barriers. So what I’m hoping is that it becomes so easy that people just do it at the stage where it’s not too late to do it.

I also think that the whole idea of privacy – of not having what you record go to the cloud and then be processed there – is really exciting.

And finally, voice is really a key part of people’s identity. It’s important for them personally but also for the people that love them. And so anything that makes it easier for someone to have a voice that sounds like them is really powerful.

I’ve already seen some reactions from our community, especially those people that are part-time AAC users, which means they sometimes speak, and sometimes they use a device. They love the idea of being able to, at no cost, easily record their own voice so that they can sound like themselves. So that’s a whole category that would not typically get any funding today, which makes other solutions challenging from a cost perspective. So, I think that’s a group that will be really excited about it.

For us as developers, we don’t know yet what it will take to integrate this Personal Voice feature, but it definitely sounds like something that’s interesting to do.

What’s also exciting about this is, as I mentioned, there are other companies that do similar things, but as a developer, that means I need to include this SDK for that company and that SDK for another company. When there’s a new iOS version, I need to get new versions of those SDKs and test them again. That’s been a barrier for us to include this kind of technology in some of our products. And so having a first-party solution from Apple that addresses this will lower the barrier for us to offer this kind of feature to more users. So I think that’s a big plus from a developer perspective.

How about Assistive Access? I’ve got to imagine that having the ability to put your app in an Assistive Access setting would help with keeping people who use the app, especially children, focused on your app in settings like schools.

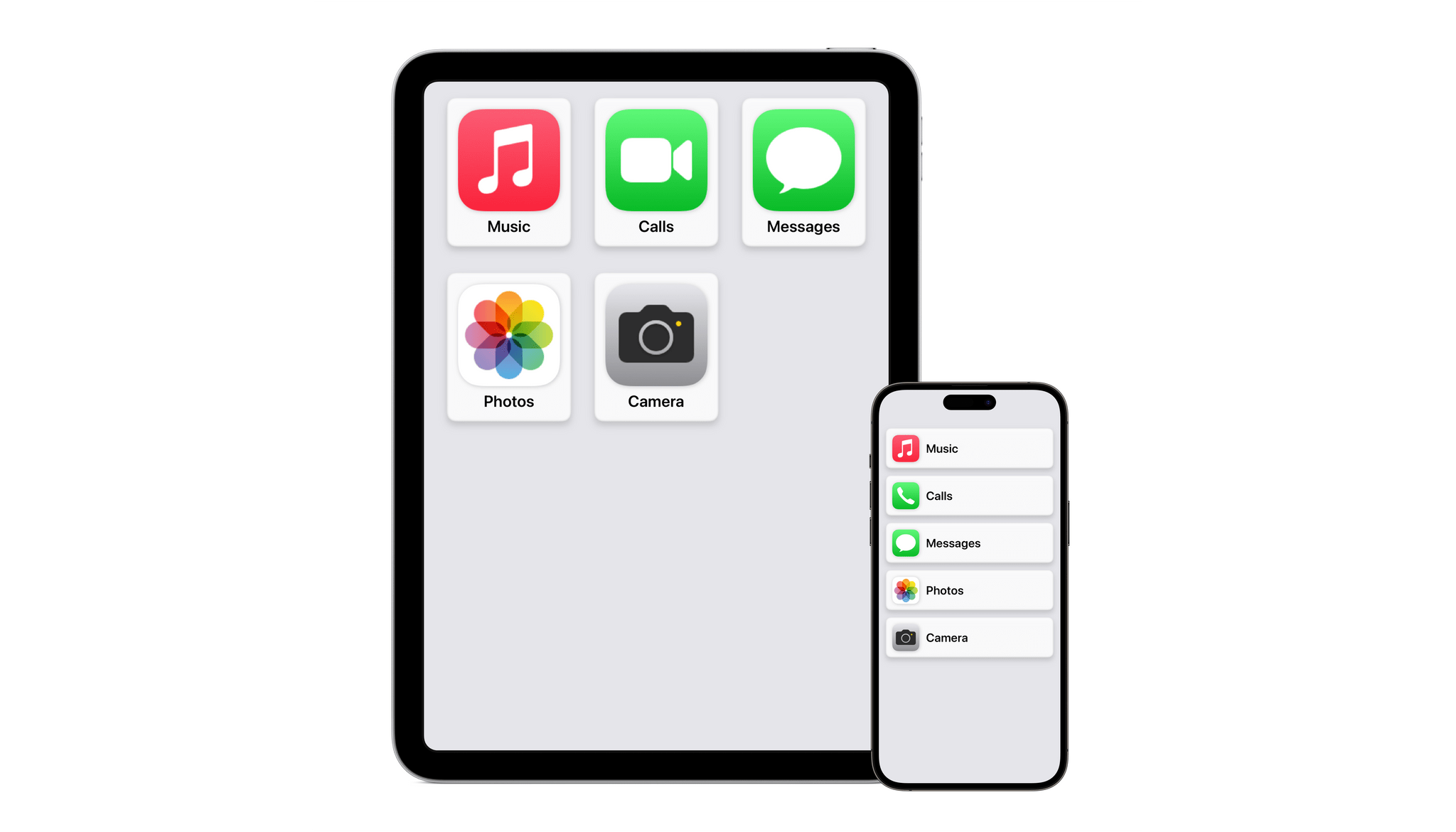

Niemeijer: I see Assistive Access as a really nice extension from what we have with Guided Access. Guided Access for the last decade allowed you to lock someone into an app, and block out certain parts on screen, but it didn’t allow you to switch back and forth between multiple apps. And being able to set something up where a user can switch between two apps is actually really interesting for us because it allows people to kind of go back and forth between two or three products that are really valuable to them, rather than that they need someone else to come in, unlock one and lock in the other. So I think it really gives people more autonomy but in a safe kind of environment.

I also expect that for the elderly population, this is going to be huge. That’s not our primary target group, but looking around me and also reading what other people say, including in my own team, there’s a lot of potential there. So I see this not just as a boon for people with cognitive disabilities but for anyone who doesn’t need all those power user features and is afraid to get lost.

And having a more forgiving environment also means that people are going to use technology more. Because if you go to someone today who is a little fearful of technology, and they see all the options they have there, they might just not use this product, or they might not use this particular app because they’re afraid they might break it or get stuck in a corner. And an environment like Assistive Access should eliminate a lot of that fear and give them the essential functions that they’re really looking for. So I think it’s huge.

That leads really well into my next question, which is something you’ve written about in the past – the democratization of communication. What’s your perspective on how devices like the iPad and the iPhone have democratized communication?

Niemeijer: In the days before iPhone, in a country like the US, only a fraction of the people that could have benefited from this kind of technology got access. Devices would cost anywhere from two to three thousand dollars for a small little handheld iPod touch kind of device to ten to fifteen thousand dollars for more of an iPad-like device. And when I say ‘like,’ they were heavier and clunkier but with a bigger screen than the small devices.

So what happened was that by putting this kind of technology on consumer devices, it de-stigmatized the fear of a school. A student might have one of those devices, but when they went out to the playground, it was locked in the cupboard because, God forbid, it got damaged because it was $15,000. The moment the iPod touch started being used in schools, and later the iPad, suddenly it could be taken to the playground.

Kids would suddenly be the cool kid because they have the device, whereas before, they were the weird kid that had a clunky device. Younger kids suddenly got access because these dedicated devices, where before, the cost of them typically meant that you might be eight or ten years old before you would get anything. Now, a two-year-old or a four-year-old can get a device, and the earlier in your development that you get access to a piece of communication, the more opportunities you have in terms of language development. In terms of learning, you’re not going to miss out. So that’s been really big.

The other part was that the kind of people who got access expanded. In the past, it was typically people with cerebral palsy and people with physical disabilities that would get funding and would get these devices, but with first the iPhone, iPod touch, and then the iPad, this really opened up to people with Down syndrome, autistic people, and people were also suddenly able to make that decision, because they could buy the device in an Apple Store, and then go the App Store, even if a professional would say, “I don’t think he’s ready yet for this,” or “I don’t think it’s a good choice.” So that really democratized access, made it more affordable, and today, the number of people who get access to this technology has multiplied maybe by a factor of 10 every year.

We’re still nowhere near where everyone who would benefit from the technology can actually get it, but we’re so much further ahead than before the App Store.

Where do you hope technology will take AAC apps in the future?

Niemeijer: I think one of the biggest challenges is in the educational environment. What we see is that, especially in the US, schools are required by law to provide these kinds of devices to provide communication, but teachers are struggling to use that effectively in the classroom and support the students that use this kind of technology effectively.

What we’re trying to do is work toward them actually being helpful to the teacher. So in our latest product, Proloquo, we actually significantly expanded the default vocabulary with a lot of the words necessary for the curriculum, and I think if we want AAC to further take off from a technology perspective, we really need to look more at how we can help teachers benefit from it, and not only have yet another thing that they’re responsible for in the classroom.

You make apps that are specifically targeted at accessibility, but what advice would you give to your fellow developers who maybe aren’t making accessibility apps but really want to incorporate some of Apple’s accessibility features in their own apps? Where should they start, and what are the kind of things they should be thinking about to do more with their own apps?

Niemeijer: One of the things I think to think about is how making your app accessible is not only good in terms of it’s a good thing to do, it’s not only good because you’ll get more customers who would otherwise not be able to use your app, but it can actually help you in your development and testing. If you make sure that every element in your app is accessible, for example, for a VoiceOver user who cannot see the screen, that also means that with the tools that Apple provides, you can actually build automated tests to see if your app function correctly.

To give you an example, some of our apps cover quite a few languages, and for the App Store, you need to upload screenshots in multiple device sizes for multiple languages. You make a change to your app, and things look slightly different, so you have to do it again. So what we did is we used those accessibility features to automate navigating the UI so we could automatically capture the screenshots. And what used to take a few days, it now runs on a machine for a few hours independently.

So it cuts both ways. You get better products, you get more accessible products, but you can also actually enhance the quality for everyone.

And sometimes, you don’t yet see the use of certain things, but then Apple introduces something like Voice Control, where you can actually speak to your device to interact with it. That opens a whole other kind of use for it. Automation features typically make use of these kinds of technologies.

So, I would say it’s one of those things when you’ve never done it, it looks really scary, but it’s actually really easy to do. And Apple provides a really great foundation. If you use standard elements, you get most accessibility features, like 95% for free, and the other 5% is not going to keep you working through the night.

When you make custom elements, you need to do more work. But again, it’s manageable, and the benefits to users and also to being able to deliver good quality, well-tested software are huge as well. So we do it for every product we do, even if we are not necessarily expecting that this product is going to be used by this category of people who would need this particular piece of accessibility. We see this as something that’s a must-have for whatever we do.

Thanks to David Niemeijer of AssistiveWare for joining me to talk about Apple’s upcoming accessibility features, and thanks to Apple for arranging for today’s interview.