Here’s a thought experiment. Let’s imagine that Apple decided to combine their engineering resources to form app teams that delivered both iOS and macOS versions of applications.

In such a scenario it may seem logical to retain application features common to both platforms and to remove those that were perceived to require extra resources. Certainly Automation would be something examined in that regard, and the idea might be posited that: “App Extensions are equivalent to, or could be a replacement for, User Automation in macOS.” And by User Automation, I’m referring to Apple Event scripting, Automator, Services, the UNIX command line utilities, etc.

Let’s examine the validity of that conjecture, beginning with overviews of App Extensions and User Automation.

What are App Extensions?

App Extensions (often called simply “extensions”) are essentially application (or framework) plugins that provide the functionality to perform specific tasks, such as manipulate an image, post media items to social services, share items and documents, or filter an audio stream. There are many types of extensions, and you control their use in the Extensions preference pane of the System Preferences application.

But the most important ability of App Extensions is that they can be used by apps other than the one in which they are contained. For example, an application that creates QR codes may also contain an app extension that enables other applications to use the containing application’s functions to create and place QR codes within their own documents.

Extensions physically exist as bundles (with the file extension “appex”) placed within their containing application’s bundle. However, macOS will make them available while you are using other applications by placing them at “extension points,” such as in the Share Menu, or in the Photos application when it is in edit mode.

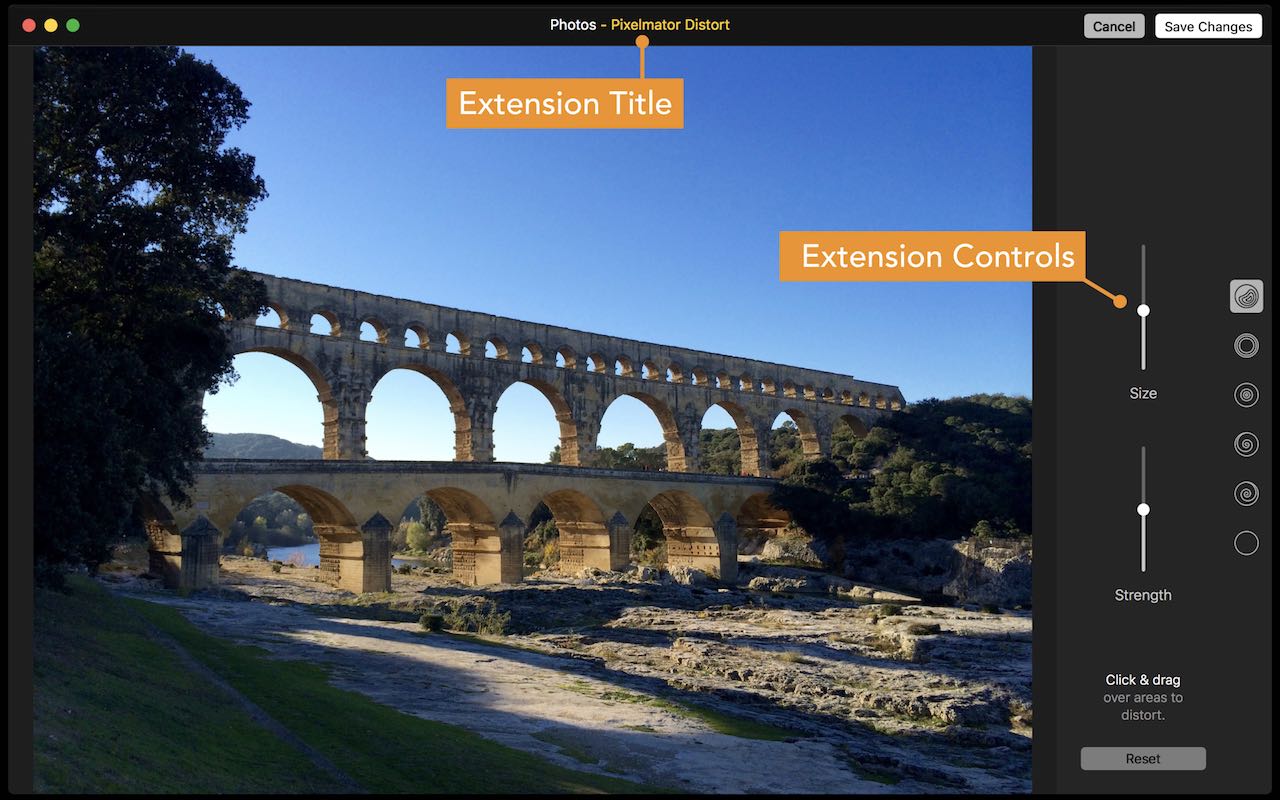

In the example shown above, extensions included in the Pixelmator application are available as filter and editing options in the Photos application. When an extension is chosen, the Photos interface changes to display the image and extension controls.

You can make edits to the image using the tools provided by the extension, click the “Save Changes” button, and you will be returned to the standard Photos interface.

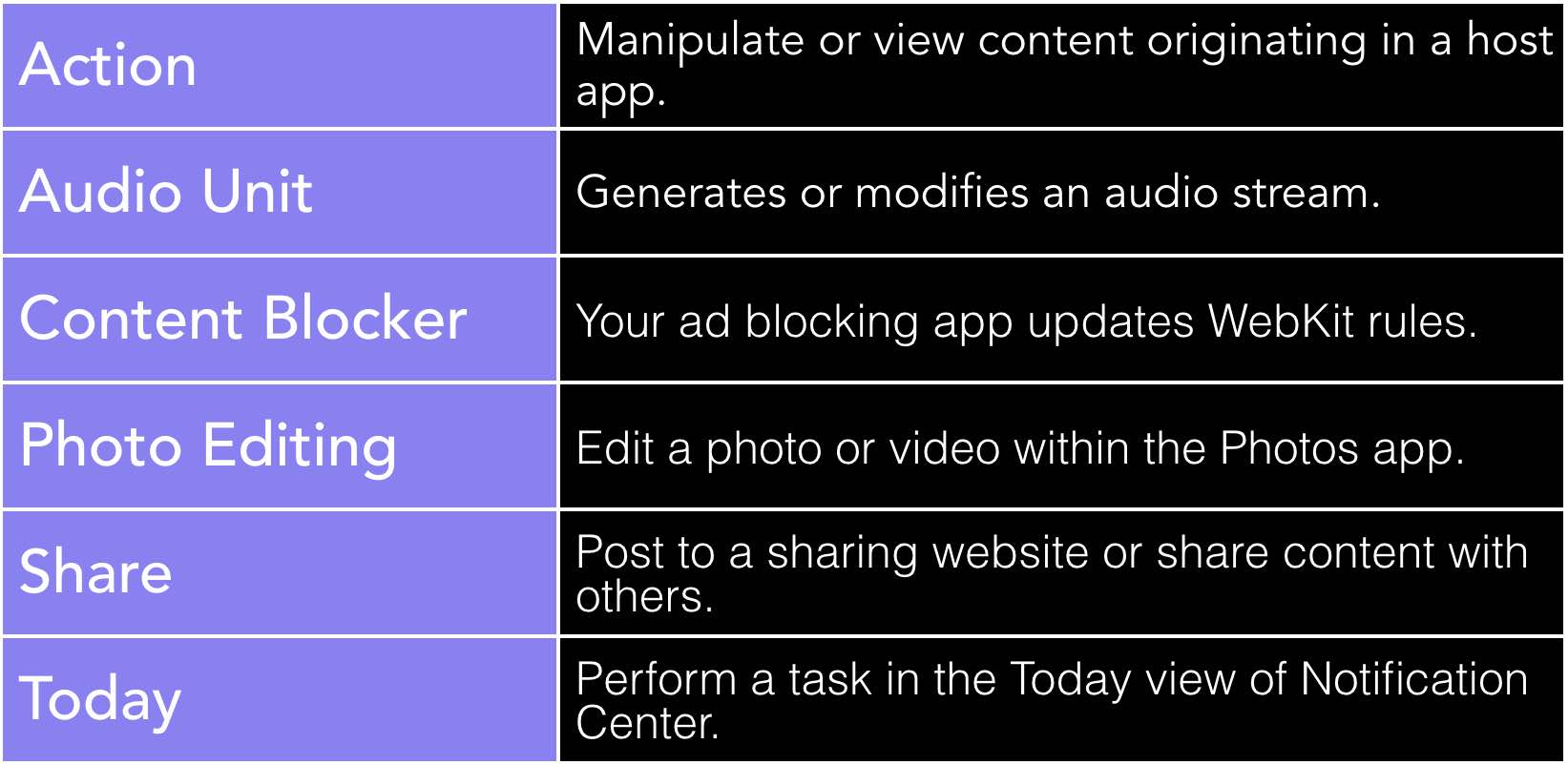

Extension Points are exposed in multiple locations in macOS, from additional data sharing options added to the Share Menu, to inline content such as the Markup extension in Mail. The chart below lists some of the macOS extension points (types):

How do App Extensions work?

By design, most App Extensions follow specific rules governing how they function. In general:

- Some app extensions, like content blockers, can run without user interaction. But other extensions, like those that manipulate images, are triggered only by direct user action, such as selecting a menu item, or pressing a button.

- Once triggered by the user, the extension is provided a copy of the current object or data selected in the hosting application. The extension may display a user interface (if needed), then processes the data, and returns the edited data to the hosting app.

- By design, App Extensions have restricted access to resources outside of their bundle, and have restrictions placed upon them in regard to their access to the macOS frameworks, networks, and the user environment.

Who creates App Extensions?

App Extensions are created by Apple developers in Xcode using either the Swift or Objective-C programming languages. Non-programmers are not the target audience for developing app extensions.

App Extensions Summary

App Extensions are developer-created application plugins, exposing powerful functionality within multiple applications at pre-determined “Extension Points,” such as in the Share Menu, or in the Today view of the Notification Center. App Extensions are executed within a defined set of parameters and restrictions, and their scope is often limited to processing the selection in the host application.

What is User Automation?

The term User Automation represents multiple technologies and architectures whose purpose is to enable the user to create simple or extended workflows for editing documents, processing data, and performing repetitive tasks.

The technologies of User Automation operate with the user’s level of authority and are not restricted in the scope of their abilities: whatever the user can do, they can do. They have unrivaled access to the frameworks of the operating system, and to the extensive library of UNIX tools that ship with macOS. And most importantly, AppleScript, JavaScript (JXA), and Automator can directly query and control scriptable applications using Apple Events, the inter-application communication technology that has existed on the Mac since System 7.

macOS applications that support Apple Events are said to be “scriptable,” in that they allow the built-in Cocoa scripting frameworks of macOS to communicate with and control the application and its elements. Every “scriptable” application includes a “dictionary” providing detailed information about every scriptable object in the application and the commands used to interact with them. As an example, the dictionary excerpt shown below is from the Keynote application’s dictionary, and describes the slide object of a Keynote presentation document.

slide n : [inh. iWork container; see also Compatibility Suite] : A slide in a presentation document.

elements

contains audio clips, charts, iWork items, lines, movies, shapes, tables, text items; contained by document.

properties

base slide ( master slide ) : The master slide this slide is based upon.

body showing ( boolean ) : Is the default body text item visible on the slide?

default body item ( text item r/o ) : The default text item container for the body text of the slide. Its visibility is determined by the value of the body showing property.

default title item ( text item r/o ) : The default text item container for the title text of the slide. Its visibility is determined by the value of the title showing property.

presenter notes ( rich text ) : The presenter notes for the slide.

skipped ( boolean ) : Is the slide skipped?

slide number ( integer r/o ) : The index of the slide from the beginning of the document. Note: skipped slides have a slide number value of -1. Un-skipped slides have a positive slide number value.

title showing ( boolean ) : Is the default title text item visible on the slide?

transition properties ( transition settings ) : A list of key/value pairs for the properties of the slide’s transition.

responds to

get, set, delete, exists, make, move, duplicate

Using this dictionary, scripts written using the macOS scripting languages can create, move, duplicate, and delete slides, as well as change their master slide, read, set, and edit their displayed text, add images and video elements, and even adjust whether they are skipped or shown. No other architecture or framework in macOS offers the ability to query and control the internal workings of applications like Apple Events. And most of the important productivity applications, such as Microsoft Office, Adobe InDesign, and the excellent suite of apps from the Omni Group, include robust and extensive scripting support, and are the “go-to apps” for implementing powerful user automation workflows.

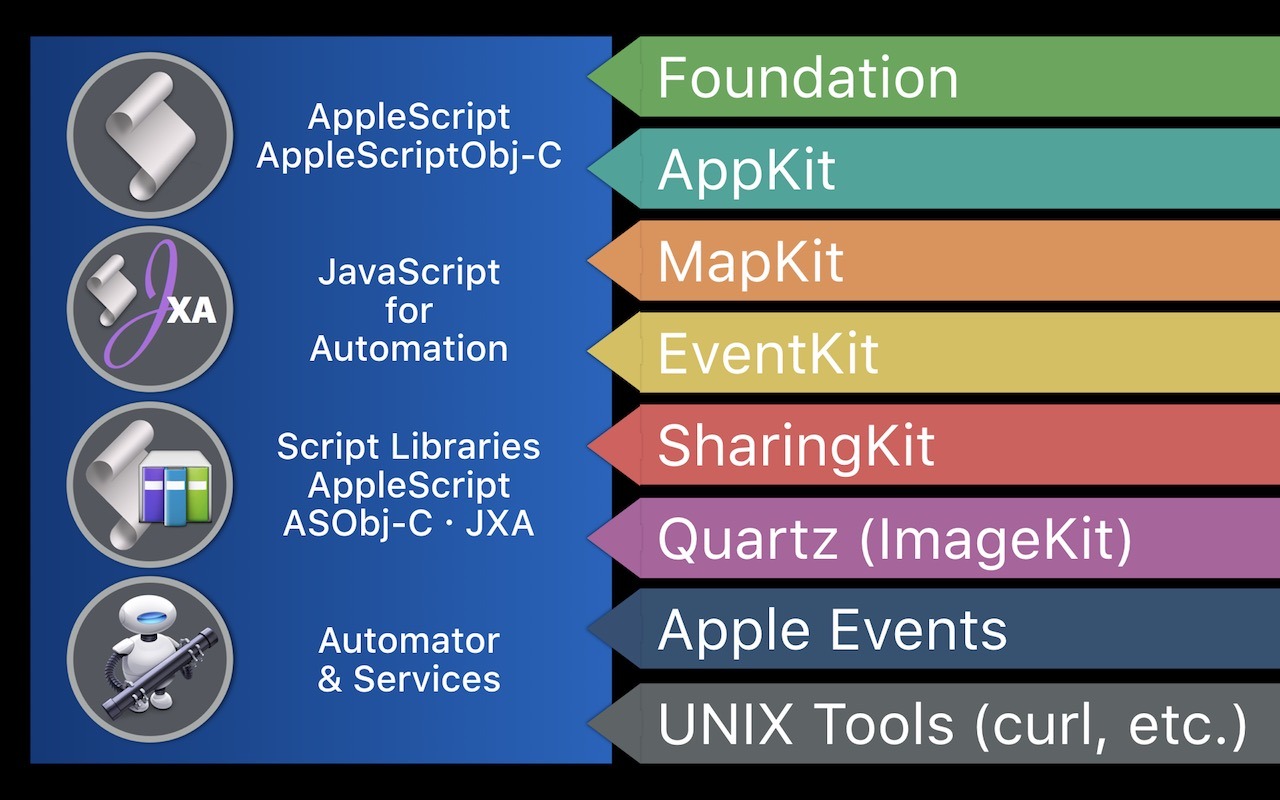

Apple Events are used to communicate with applications. For communication with the OS and its tools, the User Automation technologies of AppleScript and JavaScript (JXA) have integrated code “bridges” that provide them access to all of the Cocoa frameworks, some of which are listed in this graphic.

Using these frameworks as well as the default UNIX tools of macOS, the scope of what scripts can do expands to an impressive range of abilities.

And since User Automation can freely work between applications and frameworks, creating workflows that involve multiple apps and the transformation of data are common practice. For example, the workflow shown in the animation below begins with converting a table in a Numbers document into a chart in Keynote, then adding text, generating a QR code, and finally sending the completed Keynote document in an email message. All of these actions are possible with user automation.

Below is the AppleScript script code used to transfer and transform Numbers table data into a new chart in Keynote. As you can see, scripting support (Apple Events) provides direct access to the internal workings of the iWork applications. An Apple Events-based script can deep query the selected table object in Numbers to retrieve a range of data, and then use the retrieved data to create a new slide and chart in Keynote.

tell application "Numbers"

tell the front document

set aTable to the first table of active sheet whose class of selection range is range

set aRange to cell range of aTable

tell aTable

copy {column count, row count} to {columnCount, rowCount}

copy {header column count, header row count, footer row count} to {headerColumnCount, headerRowCount, FooterRowCount}

set dataColumnCount to columnCount - headerColumnCount

set dataRowCount to rowCount - headerRowCount - FooterRowCount

if headerRowCount is 0 then

set columnNames to {}

repeat dataColumnCount times

set the end of the columnNames to ""

end repeat

else

set columnNames to the formatted value of cells (headerColumnCount + 1) thru -1 of row headerRowCount

end if

if headerColumnCount is 0 then

set rowNames to {}

repeat dataRowCount times

set the end of the rowNames to ""

end repeat

else

set rowNames to the formatted value of cells (headerRowCount + 1) thru (FooterRowCount - 1) of column headerColumnCount

end if

set topLeftRangeCellID to the name of cell (headerColumnCount + 1) of row (headerRowCount + 1)

set bottomRightRangeCellID to the name of last cell of row ((FooterRowCount + 1) * -1)

set tableDataRange to range (topLeftRangeCellID & ":" & bottomRightRangeCellID)

set cellValuesArray to value of every cell of tableDataRange

set chartData to {}

set x to 1

repeat ((count of cellValuesArray) div dataColumnCount) times

set the end of chartData to items x thru (x + (dataColumnCount - 1)) of cellValuesArray

set x to x + dataColumnCount

end repeat

end tell

end tell

end tell

tell application "Keynote"

activate

tell front document

set aSlide to make new slide with properties {base slide:master slide "Blank"}

tell aSlide

add chart row names rowNames column names columnNames data chartData type vertical_bar_2d group by chart column

end tell

end tell

end tell

And if you prefer using a scripting language other than AppleScript, the same Apple Event functionality could be delivered via a JavaScript (JXA) script…

var Keynote = Application('com.apple.iWork.Keynote')

Keynote.activate()

var frontDocument = Keynote.documents[0]

var aMasterSlide = frontDocument.masterSlides["Blank"]

var newSlide = Keynote.Slide({baseSlide:aMasterSlide})

frontDocument.slides.push(newSlide)

Keynote.addChart(newSlide,{rowNames:rwNames, columnNames:colNames, data:chartData, type:"vertical_bar_2d", groupBy:"chart row"})

Excerpt shown here, open in script editor to see the full script.

…or by using Automator actions for Keynote.

Automator

And then there’s Automator. The unrivaled tool for creating your own “automation recipes” using a simple drag-and-drop process of stringing together nuggets of predefined functionality (Automator actions) into “workflows.” Saved workflows can be executed at integrated extension points throughout macOS, including: as contextual System Services, as Image Capture and Print to PDF plugins, as Folder Actions, as Script Menu items, as Calendar alarms, and even as stand-alone applets or droplets.

There’s a common misconception that Automator is “visual-AppleScript,” but Automator is actually language-agnostic. Its “actions” can be written in nearly every macOS-supported automation language: AppleScript, AppleScriptObj-C, JavaScript, Shell, perl, python, ruby, and Objective-C. Automator can drive Apple Events, the UNIX utilities, and the Cocoa frameworks, within a single workflow. Automator also has an extensive variable architecture for capturing, generating, and reusing data during the execution of its workflows.

Automator is unprecedented in its scope and abilities in macOS. No application or system service comes close to matching what it can do.

But the most amazing thing about Automator is that powerful automation tools can be created by users without writing a single line of code—like this contextual system service that combines the PDF files selected in the Finder:

Who creates User Automation tools?

Which brings up the question: who creates User Automation tools?

In my 23-years of working with customers and businesses around the globe, it is my observation that the majority of automation solutions are created in-house by customers and employees, motivated to address the challenges, complexities, and redundancies they face in their day-to-day work.

Of course this is not to say that I have not witnessed numerous solutions created by professionals for businesses, some of which involved very elaborate and powerful codebases, but much of the time an automation solution is as simple as a script or collection of scripts created by someone who is not a programmer or developer.

Automation tools aren’t limited to scripts and some may display interfaces (such as Automator actions) for interacting dynamically with the user. These tools are usually written in Xcode, using the provided AppleScript application and Automator actions templates. Xcode automation projects can incorporate all of the standard UI elements, outlets, actions, and bindings used in the creation of traditional macOS and iOS applications.

For writing AppleScript or JavaScript (JXA) scripts, you can use the Script Editor application that ships with every copy of macOS, or for composing and editing AppleScript and AppleScriptObj-C scripts you can use feature-rich 3rd-party editors like Script Debugger that include code-completion and step-by-step debugging.

Summary

User Automation involves a variety of languages and technologies. The native Apple Events architecture of macOS provides the means for communicating with applications via scripts or code. The Objective-C bridges for JavaScript (JXA) and AppleScript (AppleScriptObj-C) provide access to the Cocoa frameworks that are the foundation of macOS. And specialized scripting additions (OSAX) deliver access to the UNIX command line and the numerous utilities that come with being a UNIX-based OS. And then there’s Automator, which has access to practically everything.

But putting the technicalities aside, the whole purpose of User Automation is to serve the user of the computer, to enable a motivated customer to use and create automation tools, like scripts, workflows, and applets, without restrictions or the requirement of being a developer proficient in Xcode and Objective-C or Swift. User Automation is for the rest of us. Ah, remember that old chestnut?

Conclusion

Tubes and Wires. I came across this quote the other day:

AppleScript has survived and remained relevant during a turbulent decade-long transition, despite its unbeloved language syntax and technical hurdles, for the simple reason that it solves real-world problems in a way that no other OS X technology does. In theory, AppleScript could be much better; in practice, though, it’s the best thing we have that works. It exemplifies the Mac’s advantages over iOS for tinkerers and advanced users.

—John Gruber, Macworld, Dec 12, 2012, The unlikely persistence of AppleScript

App Extensions and the User Automation technologies have some similarities but many differences. App Extensions are written by developers. User Automation is often written by customers. App Extensions provide restricted manipulation of selected data, while User Automation enables open query and control of applications and frameworks. App Extensions represent a habitat of “approved” developer-created tubes, while User Automation is about connecting wires to application and framework APIs to create a flow. App Extensions exist as app plugins. User Automation technologies are manifested as scripts, workflows, applets, droplets, applications, services, and plugins, available globally and at extension points throughout macOS.

Based upon the information presented in this overview, it is clear that App Extensions do not provide the same abilities and functionality as the User Automation technologies of macOS, and objectively should not be considered a comparable replacement for them. Of course, this conclusion assumes that customers should retain the same level of control over their devices as provided by the current User Automation in macOS. Such is the foundation of the credo that the power of the computer should reside in the hands of the one using it.

But let’s take a step back, and think about this topic differently. Why not have both?

Perhaps it is time for Apple and all of us to think of User Automation and App Extensions in terms of “AND” instead of “OR.” To embrace the development of a new cross-platform automation architecture, maybe called “AutomationKit,” that would incorporate the “everyman openness” of User Automation with the focused abilities of developer-created plugins. App Extensions could become the new macOS System Services, and Automator could save workflows as Extensions with access to the Share Menu and new “non-selection” extension points. And AutomationKit could even include an Apple Event bridge so that it would work with the existing macOS automation tools.

App Extensions could become another type of User Automation. What a concept.

Reference Links

- App Extension Programming Guide

- JavaScript for Automation (JXA) release notes

- iworkautomation.com

- macosxautomation.com/automator

- Apple Mac Scripting Guide

- macscripter.net

- Script Debugger

- Writing an AppleScript-based Automator action

- Writing a Shell-script-based Automator action

- Xcode template for writing Automator actions for the Apple Configurator iOS device management application.