Location and Privacy

Following the rollout of Differential Privacy in iOS 10, Apple is expanding the program to learn from new data sets. At the same time, they’re also revising access to two essential iOS features: location and photos.

Location Permissions

According to Apple, 21% of apps that request access to location on iOS 10 do so with the Always authorization, which enables them to use all location services and launch them in the background. However, according to data shared at WWDC, many of the apps that implement CoreLocation’s Always access don’t actually need the features granted by this higher-level authorization, resulting in confusing permissions and, in some cases, additional power consumption and privacy concerns. Apple believes these apps could continue to function as normal with a lower level of location authorization. With iOS 11, they’re changing the way location permissions are granted.

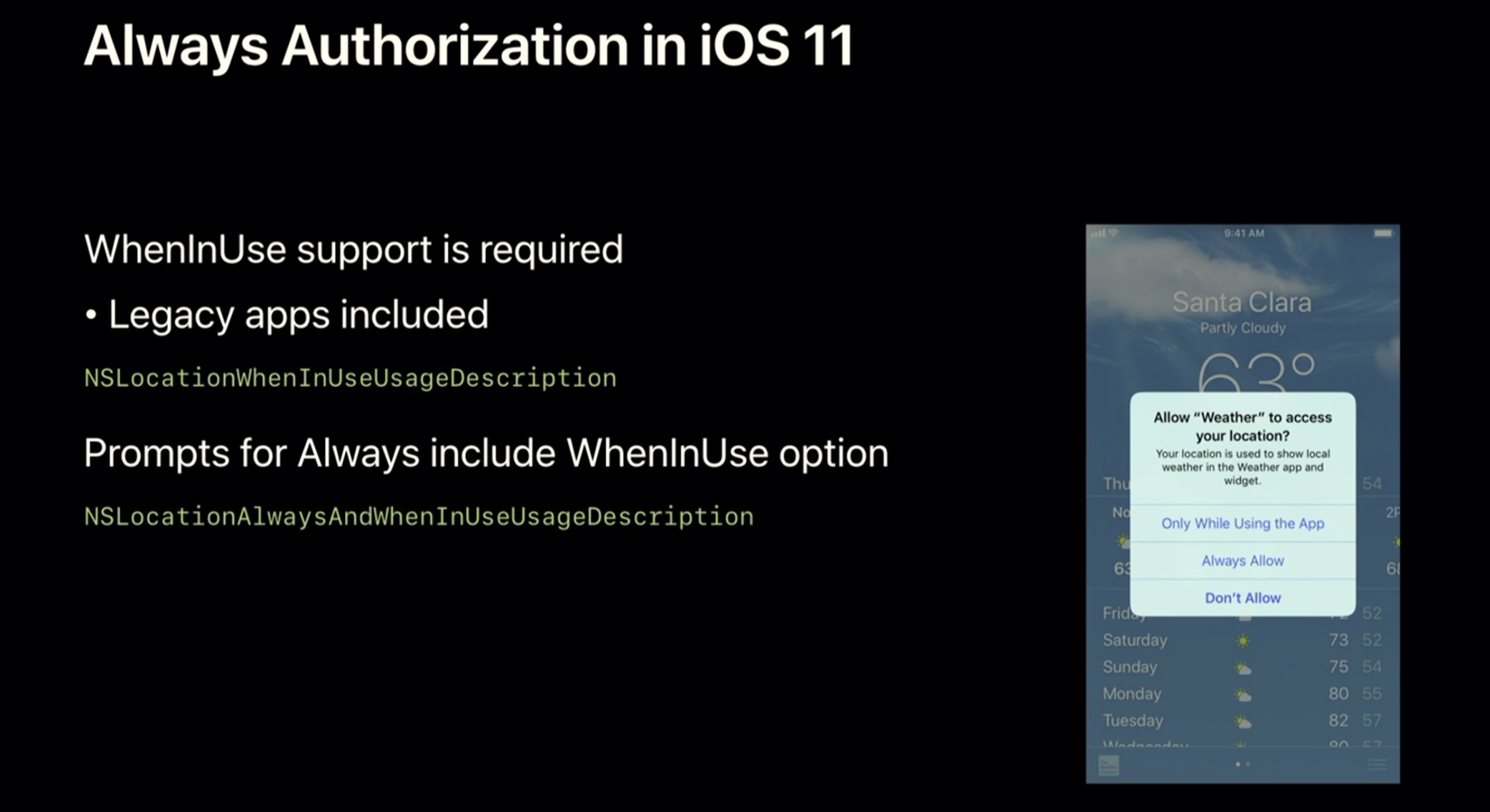

From a developer standpoint, Apple is asking apps that use the ‘Always’ authorization to also support the ‘When-in-use’ type, which provides a subset of location services that cannot automatically relaunch an app.

To match this requirement, iOS 11 features an updated permission prompt that includes three buttons and two descriptions for Always and When-in-use. From the same dialog, developers can explain why an app may want two different types of location authorizations and the practical differences between them. If an iOS 10 app that hasn’t been updated for iOS 11 requests Always location access, the prompt will also include the When-in-use option as it’s mandatory for everyone.

Apple is encouraging developers to think deeply about the location services their apps need while being respectful of their users’ privacy, trust, and understanding of an app. By combining When-in-use and Always in the same dialog (where When-in-use is the first and most visible option), iOS 11 should prevent apps from becoming useless shells unless the user grants an Always authorization.

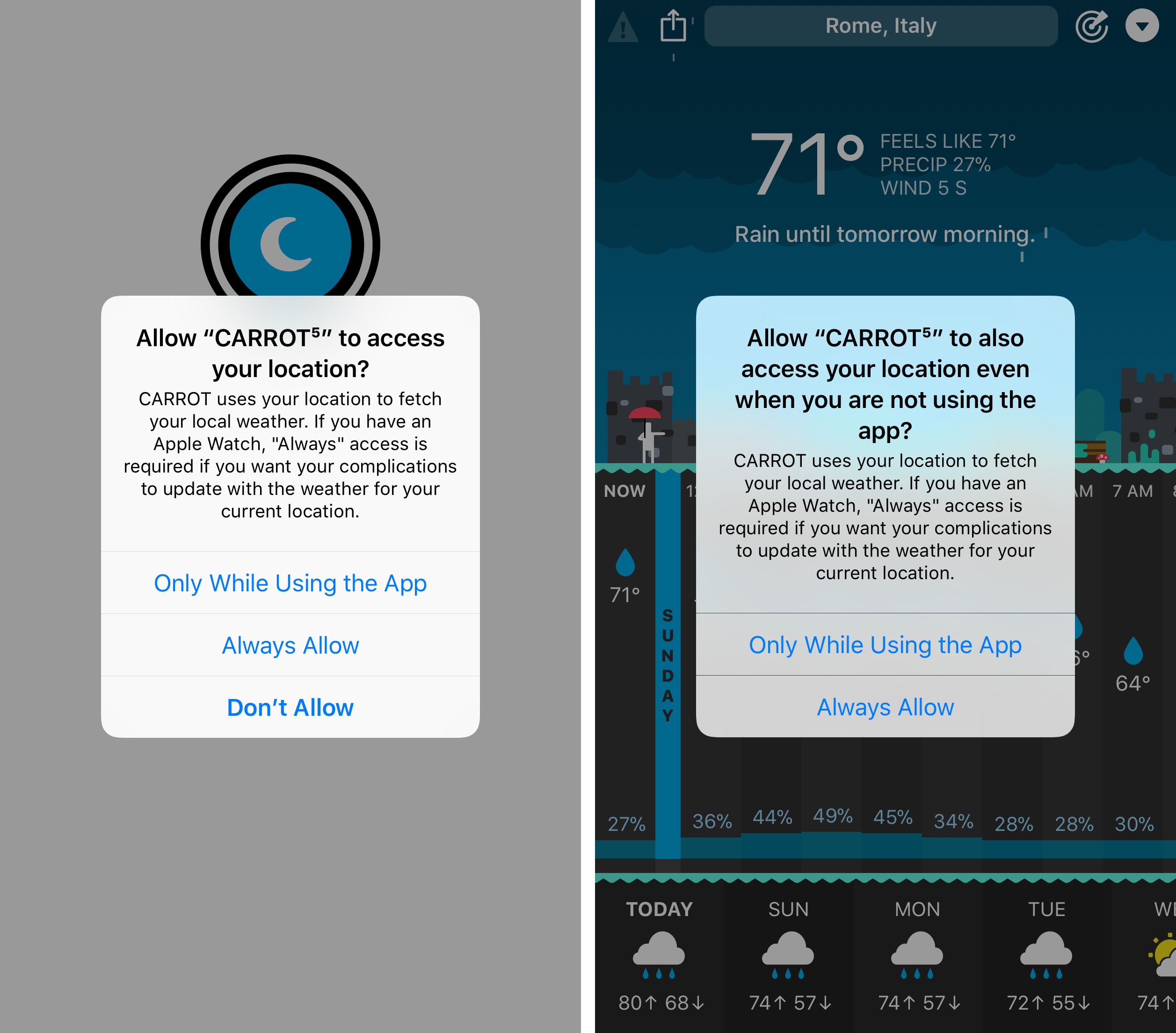

The new system also comes with a two-phased approach where apps can later ask users to upgrade their permission status from When-in-use to Always to unlock specific features. The authorization upgrade has a dedicated prompt that can be displayed contextually while using an app.

Imagine, for instance, how a food delivery app might want to request When-in-use during the onboarding process to find restaurants nearby and, after an order has been placed, ask for an upgrade to Always so the user’s delivery can be monitored in the background. Apple recommends this two-stage flow as the ideal experience for users; if an app doesn’t opt into this behavior but only asks for Always authorization in the first permission prompt, it won’t be able to upgrade or request it again if the user denies it.

iOS 11’s authorization flow should make the location-granting process more transparent and user-friendly. Unlike in iOS 10, you won’t have to manually switch an app’s permission level in its Settings page, and there’s a higher chance that most apps will default to the privacy and energy-conscious When-in-use API.

In addition to handling and presenting location permissions differently, iOS 11 has an easier way of visualizing location services. Now, a hollow arrow in the status bar means an app is requesting location; a solid arrow indicates an app is currently receiving location data.

The prioritization of CoreLocation’s When-in-use access is good for users and good for developers, who can take advantage of a native upgrade prompt to bump their permissions only if necessary. I think we’re going to see some interesting updates from high-profile location apps.

Other Privacy Changes

Location permissions aren’t the only ones being revamped in iOS 11.

The photo picker, while visually the same, has been rewritten as an out-of-process sandbox with an updated API. In iOS 11, apps no longer have to request access to the user’s entire library to import just one photo or video. Instead, after the picker is presented and once the user selects a photo, that individual item is passed to the app.

This is a considerable privacy improvement: first, it should prevent apps from gaining access to content users haven’t explicitly selected, but it should also break the functionality of fewer apps because users won’t be scared off and deny authorization. It’s supposed to just work.

In my tests with photo-enabled iOS 11 apps, I was able to import photos from the native image picker without being asked for full library access beforehand. User selection is an implied permission in iOS 11. As for saving photos into the user’s library, apps now have to ask for write permissions – an authorization that has its own alert in iOS 11.

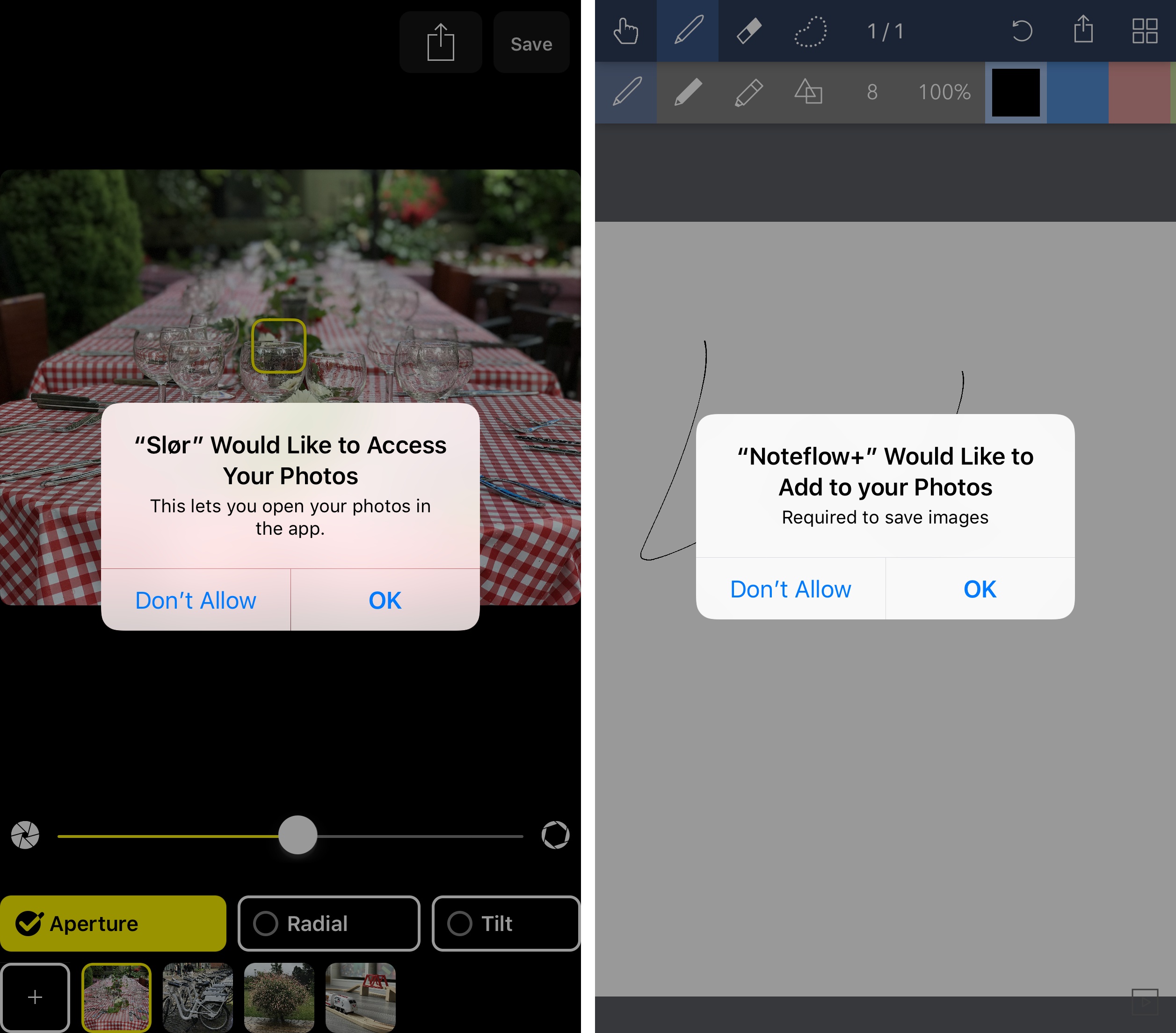

The old photo access permission prompt (left) is still required to load images from the user’s library in custom UIs. The permission prompt to save images (right) is new in iOS 11.

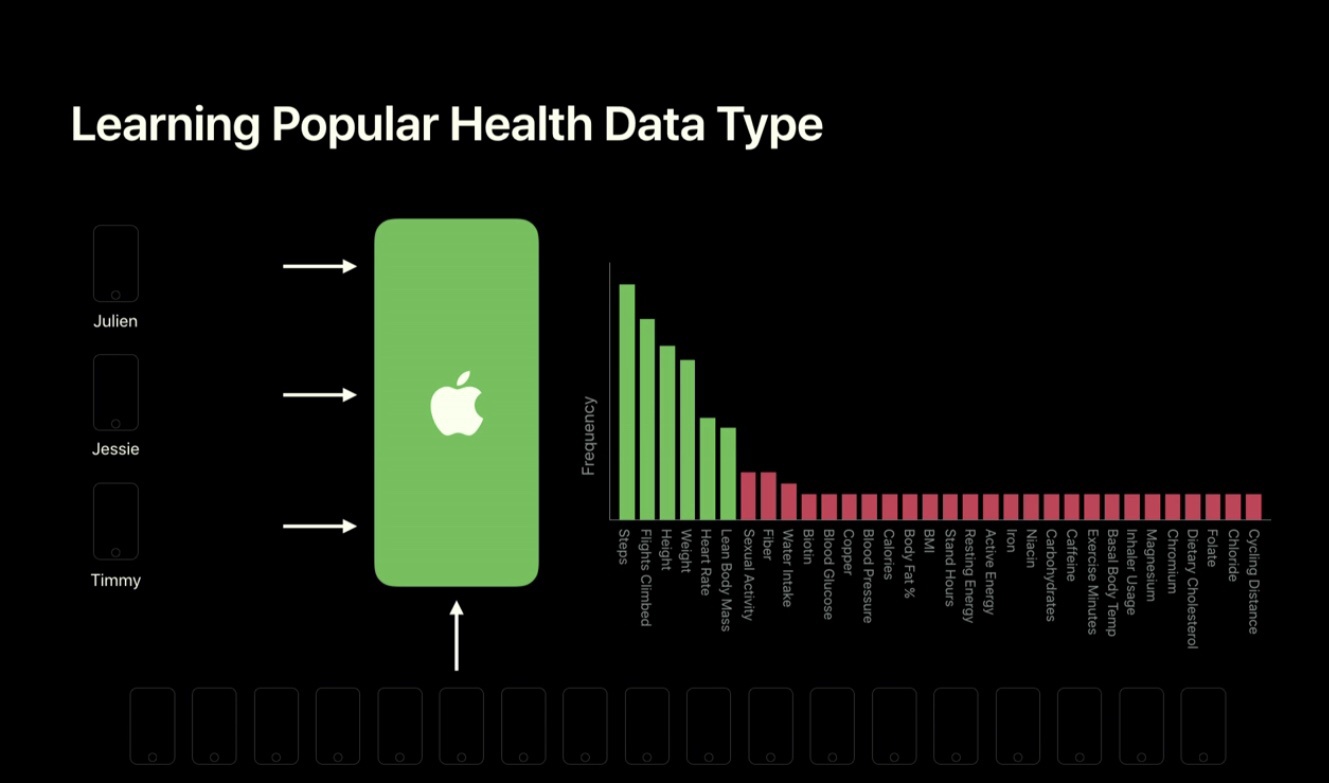

Finally, Differential Privacy. Apple claims they have received “millions of donations per day” through their engine that collects data at scale without personally identifying anyone. With iOS 11, Differential Privacy is going to learn commonly used Health data types and web domains that are causing performance issues.

The former doesn’t mean that Apple will aggregate personal Health data in the cloud – they only want to understand what the most popular categories of the Health app are. It’s possible that this data will be used to inform future development of HealthKit and Apple Watch.

As for web domains, Apple said at WWDC that Differential Privacy would monitor domains causing problems in Safari and draining resources such as memory and/or power. Apparently, they’re also going to contact publishers of the domains returned by the algorithm to work out a solution with them.

Apple seems to have some kind of master plan for Differential Privacy, but aside from the (pretty good) emoji and word suggestions in the QuickType keyboard, it’s still not clear what it ultimately entails.