Content Blockers

Safari on iOS 9 supports a new type of extension: Content Blockers. By content blocking, Apple means the ability for Safari to identify subsets of content or resources on a webpage to hide them or prevent them from being loaded altogether. Through an extension that provides a set of triggers and actions, Safari can block cookies, images, scripts, pop-ups, and other content with CSS overrides and full resource blocking.

On the surface, Content Blockers may be viewed as ad blockers for iOS, and that’s likely going to be their most popular use case, but they can do much more than simply blocking ads on webpages.

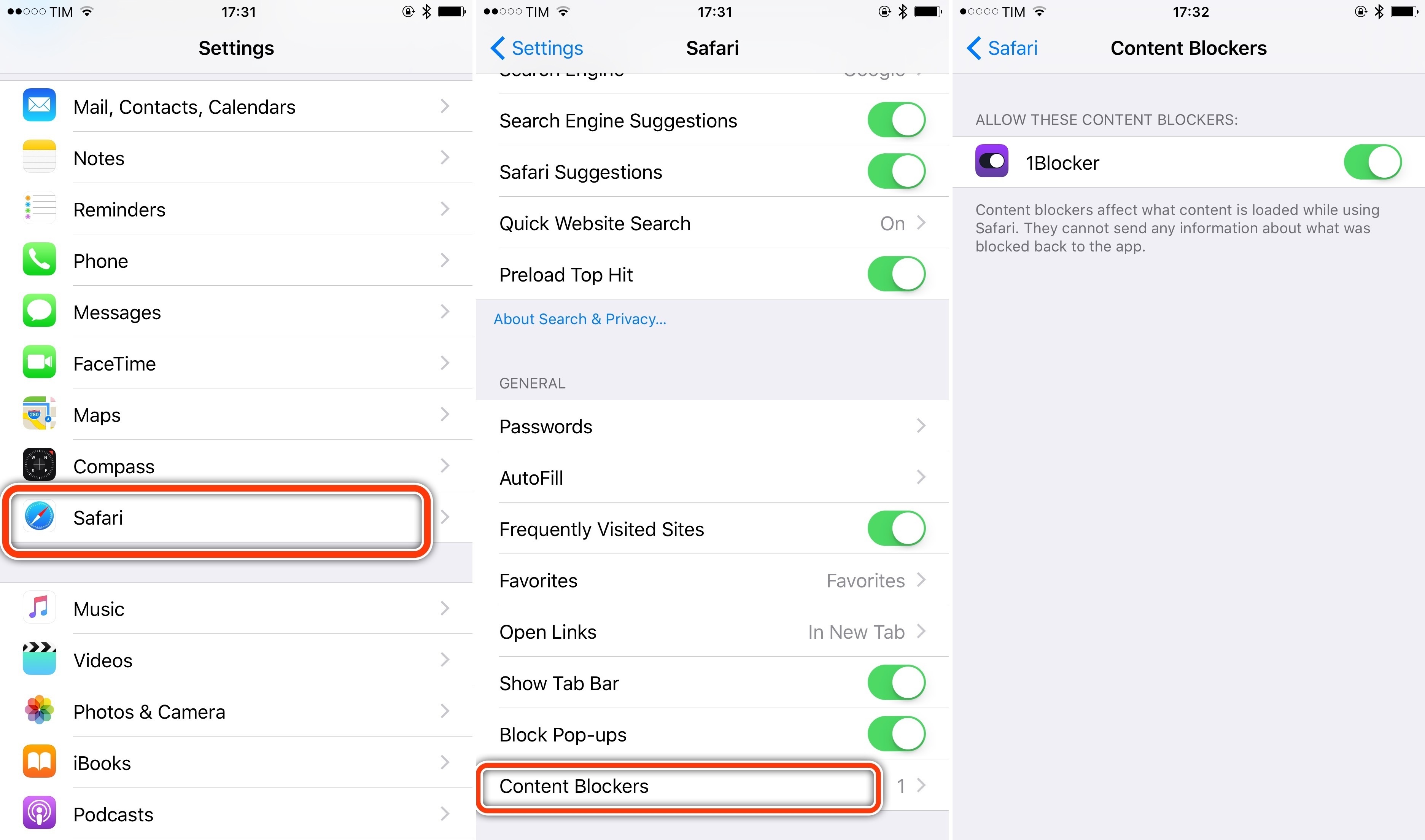

Content Blockers, like any other extension on iOS, are installed from apps you download from the App Store. An app can offer a Content Blocker extension, which you can activate in Settings > Safari > Content Blockers.

Content Blockers are based on a fast, memory efficient model that informs Safari on what to hide or block ahead of time rather than requiring Safari to consult with an app while loading a webpage. To create a Content Blocker, developers have to provide a JSON object that contains dictionaries of triggers and actions; this is then compiled into bytecode, which can be evaluated very efficiently by Safari. For performance reasons, Content Blockers are only available for apps compiled to run on 64-bit architectures, supported by the following devices:

- iPhone 5s

- iPhone 6

- iPhone 6 Plus

- iPhone 6s

- iPhone 6s Plus

- iPad Air

- iPad Air 2

- iPad Pro

- iPad mini 2

- iPad mini 3

- iPad mini 4

- iPod touch 6

In addition, Content Blockers are supported in Safari and the modern Safari View Controller; they’re not available in legacy web views built using UIWebView and WKWebView.

The model behind Content Blockers is aimed at being faster and more private than existing content blocking extensions for desktop browsers. In addition to not having to consult with a full app while loading a webpage – a task that would increase RAM and battery consumption – what the user does inside Safari is never exposed to Content Blockers. The URLs of webpages that users view in Safari with a Content Blocker installed are never passed by Safari to the Content Blocker itself. The only job of a Content Blocker is to provide a dictionary of rules; Safari takes care of everything else.

The actual rules that build a Content Blocker are organized in triggers and actions. Triggers can be filters for specific URLs, resource types (such as scripts or media), load types (first-party for resources from the same domain, or third-party from external domains), as well as filters to apply to a specific domain or to other domains except a specific one. Filters can be combined in a dictionary by a Content Blocker: for example, an app could assemble a trigger for all third-party scripts on amazon.com or a trigger that uses a regular expression to hide instances of the word “espresso” on every website except macstories.net.

As for actions, Content Blockers can either apply a CSS override (using css-display-none) to hide content or block matched content defined in the trigger. When blocking a resource, Safari won’t just load it and hide it in the background: it’ll completely prevent the matched resource from loading. From a technical standpoint, the Safari team has done a great job at making Content Blockers easy to build, fast, and private. Even non-developers can look at the JSON object powering a Content Blocker and grasp what’s going to happen once activated.

Content Blockers are a byproduct of the modern web. Given the astronomic rise of web advertising and businesses based on tracking user behavior and personal information through scripts embedded on webpages, there has been a considerable growth in the average size of webpages in recent years. It’s not uncommon to come across a webpage that goes over 10 MB of data for all the external scripts, resources, and media that a browser needs to load even if they aren’t necessarily part of the content the user is interested in.

The name ‘Content Blocker’ is something of a misnomer, since this feature isn’t meant to hide or block content, as most people would define it. Instead, they act on ads or scripts which often do block content, such as a popup image which covers what you are trying to read.

Content Blockers can also hide any page content with CSS overrides. If you’ve ever wanted to be able to hide comments, social buttons, sidebars you don’t care about, or interactive galleries from your favorite websites, Content Blockers will offer a way to do so with a few rules.

Right or wrong, this is what Content Blockers are: Safari extensions that can hide or block content with good performance and user privacy in mind. Rather than dwelling on the moral aspects of this technology, I set out to discover if Apple’s claims were reflected in Content Blockers built by developers for iOS 9.

Since June, I’ve been testing eight Content Blockers for iPhone and iPad. There was a lot of overlap between them: most developers I spoke with were building Content Blockers aimed at blocking ads and trackers, using public rules available from EasyList and EasyPrivacy. Content Blockers that only focused on blocking ads and scripts through those databases worked fine, but one was comparable to the other – and I suspect we’re going to see a lot of Content Blockers that use EasyList and EasyPrivacy with a minimal UI to wrap it all together.

Curious to have a better understanding of Content Blockers, I tried some that went beyond simple ad/tracker blocking and that incorporated CSS overrides, specific resource blocking, and user-defined filters. I ended up using two Content Blockers for this review:

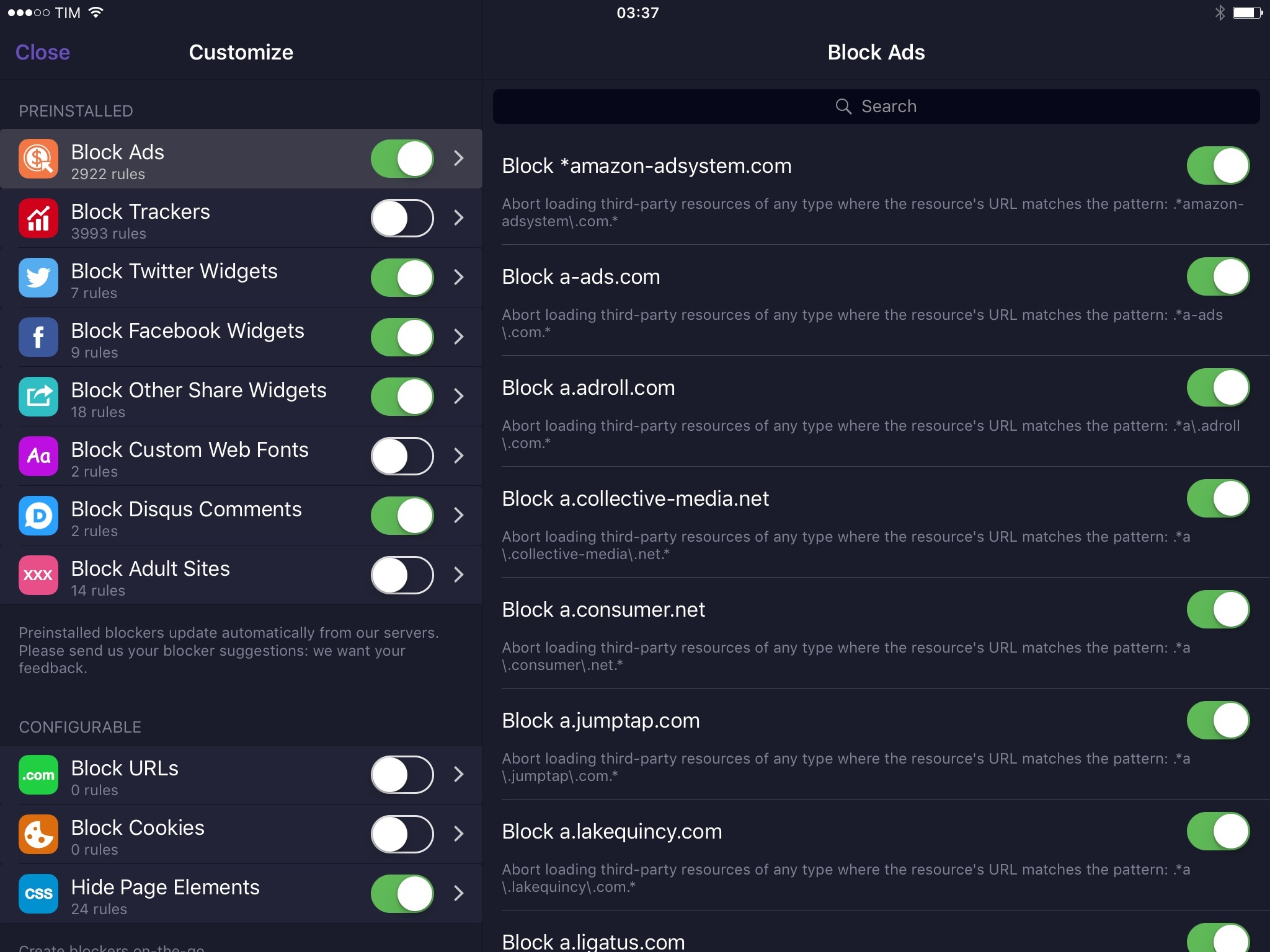

- 1Blocker, an excellent all-in-one Content Blocker that can block ads, trackers, social widgets, Disqus comments, web fonts, adult sites, and that lets you create your own rules for URLs, cookies, and page elements to hide or block. 1Blocker is Universal and it comes with over 7000 built-in rules, which you can individually turn on and off.

- Shut Up, an iOS version of the popular stylesheet by Steven Frank that hides comments from hundreds of websites and commenting systems.

With these Content Blockers installed, I ran tests on a few websites I frequently visit that heavily rely on third-party ads, tracking networks, and external resources. For some of them, I also applied custom CSS overrides to make the content more pleasing to my eyes, which involved hiding sidebars, comment sections, footers, and other boxes of content I didn’t care about.

Apple makes it easy to test Content Blockers and measure their performance: with a Content Blocker installed, a tap & hold on the refresh icon in the Safari address bar will reveal a second option to reload the current webpage without Content Blockers. This shortcut comes in handy if a site becomes problematic after blocking some of its content, but it can also be used with Safari’s Web Inspector on OS X to measure resources, size of resources, and time until the load event fired with and without Content Blockers.

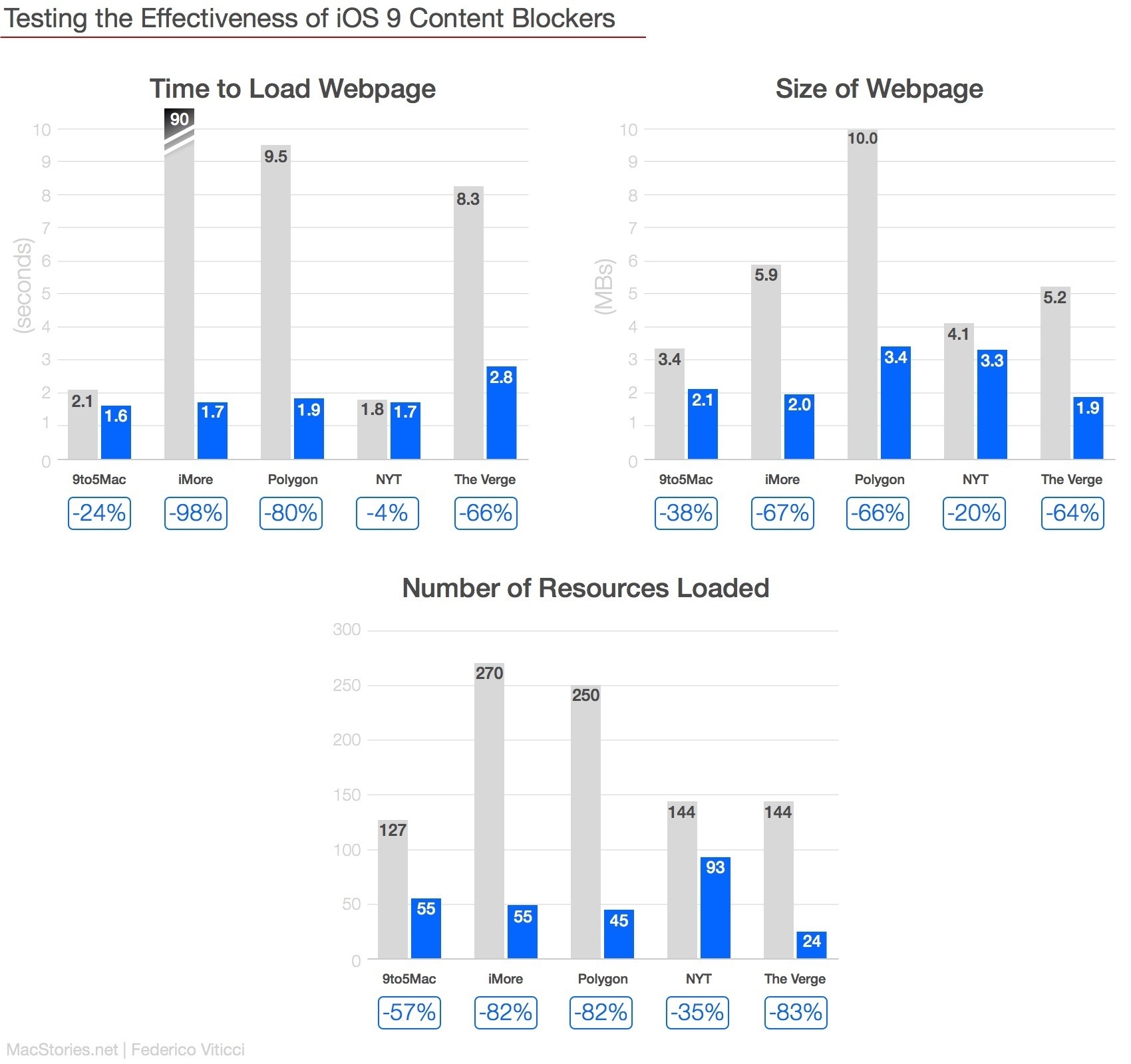

All of the following tests were performed on an iPad Air 2, on a Wi-Fi network, with caching enabled.

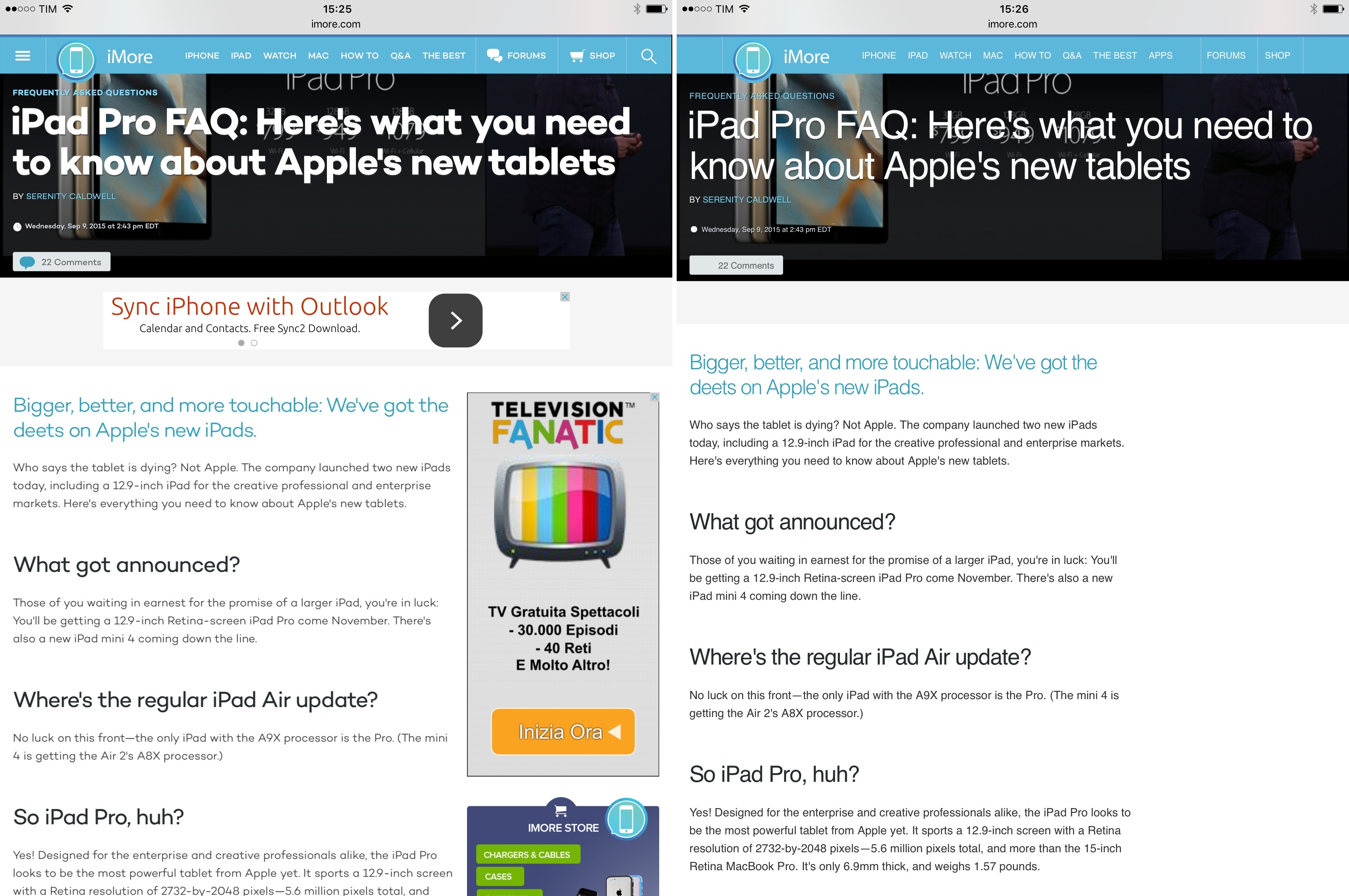

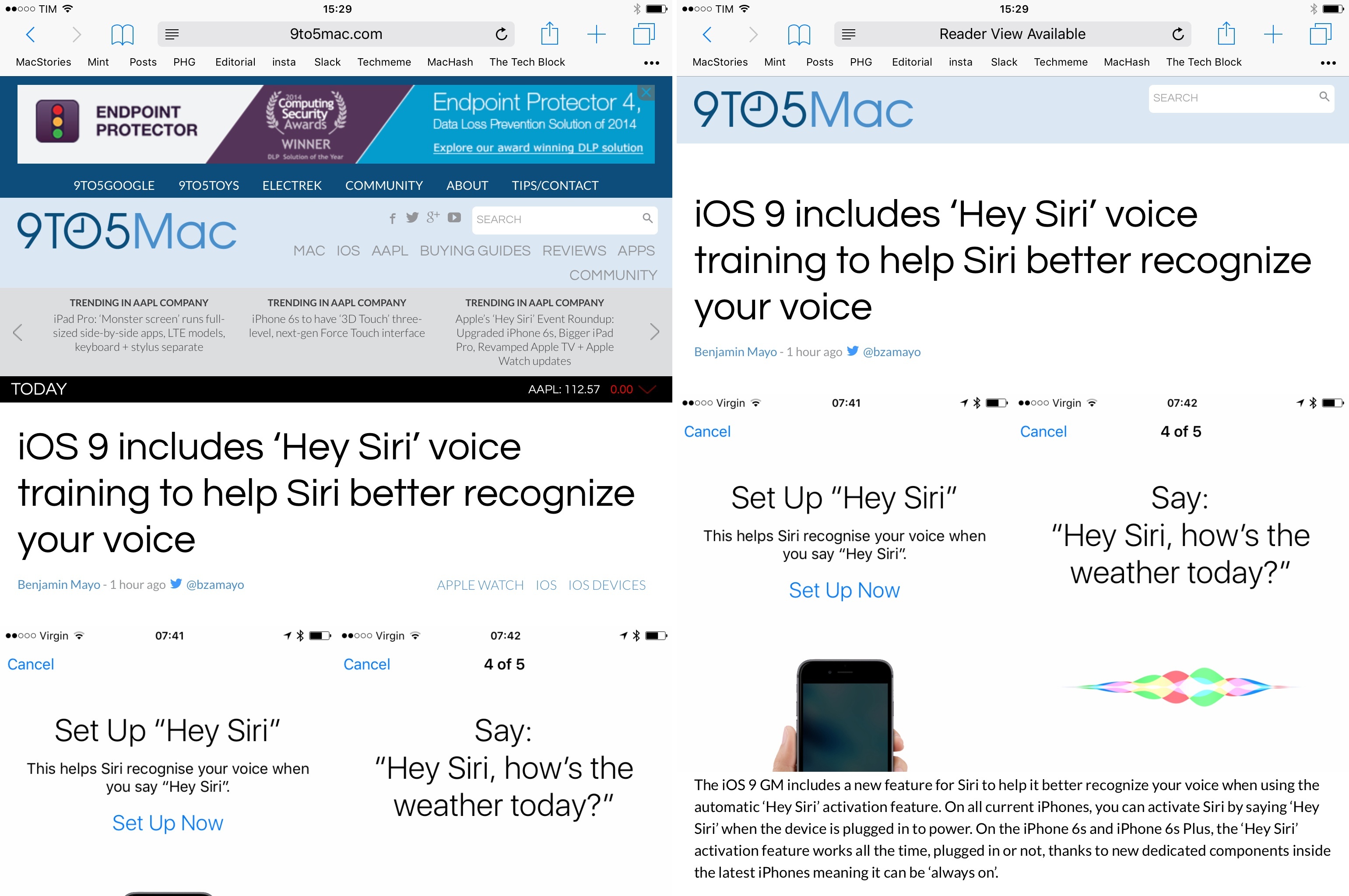

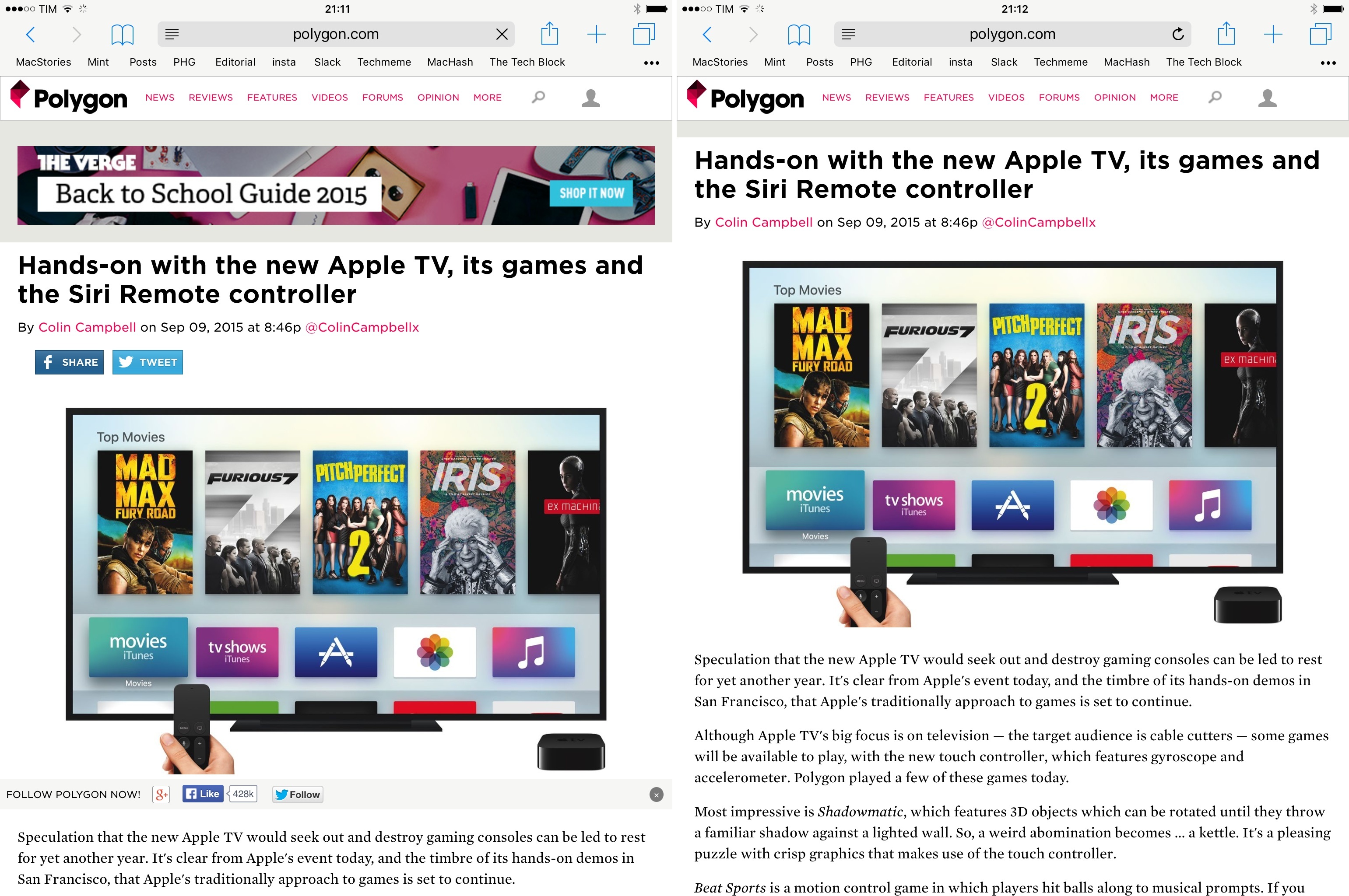

For context, you can also take a look at screenshots of a few websites before and after applying Content Blockers. Changes include both blocked resources and elements hidden via CSS.

The numbers above speak for themselves. I started using Content Blockers on my iPhone and iPad in June. Two weeks ago, out of curiosity, I decided to disable them for a few days to monitor my reaction. That’s when I realized I’m not going to disable Content Blockers if the web doesn’t improve in the foreseeable future.

I’ve gotten used to seeing webpages load in two seconds again. For the first time in years, I haven’t exceeded my monthly data cap, with hundreds of MBs of data left in my plan. In the long run, Content Blockers will give me back dozens of minutes I haven’t spent waiting for content to load alongside ads and trackers.

Effectively, using Content Blockers on iOS 9 feels like getting a new web. Lighter, faster, more private, and less cluttered.

And that’s where I feel bad, and where the entire discussion about Content Blockers lies. I don’t feel good knowing that, by using Content Blockers, I’m not supporting my favorite sites through the ad and tracking-based business model they opted for. After all, if an article on the web is given to me for free, what right do I have to complain about the means used to monetize it?

On the other hand, though, this is my time and my cellular data – money out of my pocket – and the ad-supported web has gotten out of hand. As a user and website owner, a simple article with three paragraphs of text and one image shouldn’t weigh 5 MBs and take 20 seconds to load. I can’t accept webpages that continue processing network requests in the background for over a minute, consuming battery on a device that I may need at the end of the day for an emergency. I’m all for ad-based business models – this very website is partially supported by sponsors – but is there really no better, more tasteful, less intrusive way to run a website than what we’re seeing on the web today?

As a user, am I supposed to feel bad about Content Blockers and not use them at the risk of wasting data and battery life, or should I fight back?

Apple’s answer seems clear. With iOS 9, Apple is not pre-installing any Content Blockers in Safari, and I’d be surprised if they’ll ever actively promote one on the App Store. But they have made it ridiculously easy to install and use one, with benefits that aren’t conceptual or limited to power users – everyone understands more battery and less data. When the majority of iOS users will realize that Content Blockers make Safari and the web faster and lighter, I can’t imagine why they wouldn’t want to use one. And, I bet, most of them won’t feel as bad as I did when writing this review. They won’t add sites to whitelists like I did, to enable ads on them. They won’t care about the business model of a website. They’ll just enjoy the cleaner, lighter web made possible by Content Blockers.

Apple is killing the proverbial two birds with one stone here. By building Content Blockers as extensions bundled inside apps and prioritizing user privacy and performance over anything else, they are leveraging the App Store to let users discover and install Content Blockers, which can’t observe what a user does in Safari. This is quite a change from popular desktop blockers that, by evaluating rules while a webpage is being loaded, can track user behavior and URLs.

Also, by making them exclusive to Safari, Content Blockers will likely create a powerful network effect: when users of third-party browsers on iOS (possibly made by a company based on ads) will know that only Safari supports Content Blockers, I bet that millions of them will switch to Apple’s browser.

Apple described Content Blockers as a way to add something to the experience of a webpage “by taking something away”. I’m okay with what’s being taken away, and my devices are better because of it. Content Blockers are a win-win scenario for Apple and users. As for web publishers…The times, they are a-changin’.