Conclusion

I have mixed feelings about macOS Monterey.

On the one hand, Apple has come a long way from 2018 to reposition macOS so that it’s in step with iOS and iPadOS. Many of the areas where macOS differed from Apple’s other OSes for historical rather than substantive reasons have been eliminated. I’m also a fan of most of the design changes ushered in with Big Sur last year.

On the other hand though, Shortcuts is a big disappointment. I’m all for the vision of a singular approach to automation across Apple platforms, but I’m concerned that too many people will be turned off by how frustrating Shortcuts can be to use. Still, I’m encouraged by the progress that has been made in the last couple of beta turns of Monterey. The app’s crashing has stopped and although the interface remains awkward in places, it’s improving. Even so, adoption by third-party developers has been more limited than I had hoped because of the issues with the app during the beta period, and despite the admirable addition of a long list of Automator actions, the beta cycle didn’t see much else added to the app.

That said, Shortcuts still has an incredible amount of potential to be the glue that holds together automation across the iPhone, iPad, and Mac. Some of that is possible now, but we’re still in the early stages. My hope for Shortcuts is that it continues to receive substantial improvements in point updates over the next year that fix issues but also introduces new actions. That’s certainly been something we’ve seen on iOS and iPadOS, so there’s no reason why it can’t also happen on the Mac. Waiting until the next major update to macOS would simply be too long.

When Apple revealed the first details of what would become Mac Catalyst in 2018, the Mac, its OS, and the Mac App Store felt out of step and sleepy compared to the iPhone or iPad. That’s not entirely surprising for a mature platform, but it also posed risks for the Mac, especially in a mobile-first computing world.

There are lots of good reasons for the Mac to be different from iPhones and iPads. The Mac is better suited to some tasks than an iPhone or iPad. The trouble in 2018 was that too many of the differences between macOS and Apple’s other computing platforms were the result of their development along separate paths using different tools.

Over the span of three updates, macOS has made incredible strides. It’s not surprising that not everything Apple has tried has worked. There’s still work to be done especially with young technologies like SwiftUI, which seems to be the root of at least some of Shortcuts’ problems. That doesn’t mean SwiftUI isn’t still the future for apps on Apple’s platforms – it just means the framework still needs time before it’s developed to the point where it’s the right solution for most apps.

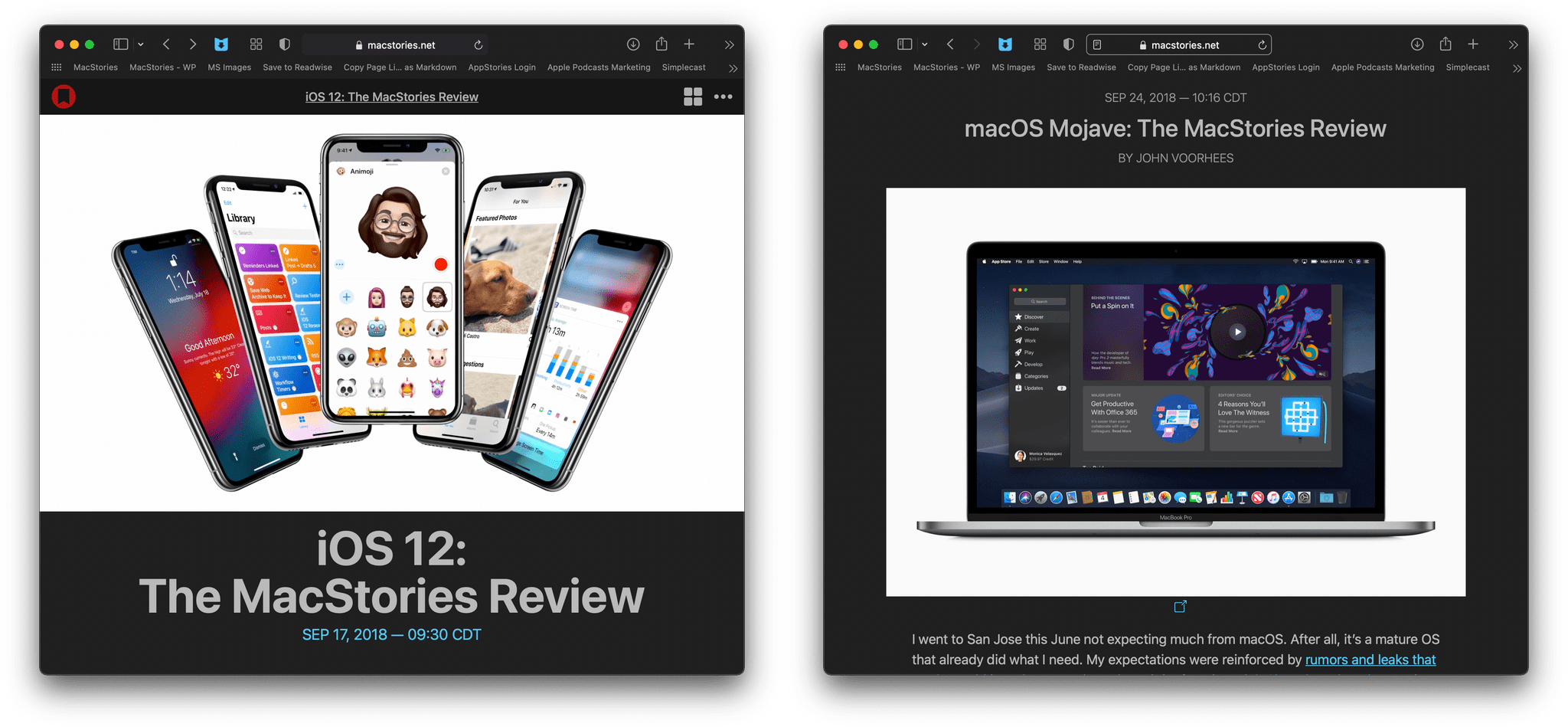

In 2018, there was virtually no overlap between our iOS and macOS reviews. Today, Apple’s system apps are being developed in sync.

What I hope, though, is that Apple listens to critiques of the past few years and spends 2022 addressing the places where macOS doesn’t yet live up to its promises. The Mac is on an exciting path and, I think, the right one. With the most powerful Apple silicon Macs on their way to customers for delivery tomorrow, the next year is a perfect time to refine macOS, correct course as needed, and further harmonize the integration of Apple’s OSes and hardware.

And while the remaining issues mean that it’s not possible to close the book on Apple’s realignment of its OSes quite yet, there’s a very simple indicator of just how far Apple has come. Look at the system apps Federico and I covered in 2018 in his review of iOS 12, compared to my macOS Mojave review, and then look at our reviews this year. In 2018, there was virtually no overlap because updates to an iOS app often took a year or more to come to the equivalent Mac app. This year, the overlap is striking, not just in the apps that have been updated but down to the individual features. It’s not that the platforms are merging: for the first time, they’re moving forward together.