Ever since I wrote about my new year’s resolutions to work smarter using better tools, compared my favorite iOS text editors, and shared some of my workflow techniques on Macdrifter, I thought it would be appropriate to share a bit more about the activity that takes up 80% of my work time: writing.

As I wrote in my comparison of iOS text editors:

Two months ago, I noted how there seemed to be a distinction between text editors focused on long-form writing, and the ones stemming from a note-taking approach. I think this difference is blurring with time, but there are still several apps that are clearly focused on distraction-free, long-form writing, like iA Writer and Byword, whereas the ones I tried for this article belong to the note-taking/Markdown/Dropbox generation of text editors. I like iA Writer and Byword, but I’m saving that kind of apps for another article.

In my workflow, there is a distinction between apps “for writing” and tools for quick “note-taking”, but in order to minimize the effort required to keep everything in sync and tied together, I set out to make sure the differences of such tasks could coexist within a single ecosystem.

My writing ecosystem is powered by Dropbox.

As I have written on several occasions in the past few months, I also spend a lot of time writing and researching in Evernote.

When I’m not using my Mac — most of the time these days — I like to write in Evernote for iPad, though I recognize the app is not perfect and could use a lot of text related improvements. The real difference, however, that I made in my writing habits recently is that I try to use Evernote for “research” articles like longer software reviews and things like this, while keeping the more “standard” posts or editorials in Dropbox. I think this kind of division makes me write better in that these articles require different, separate workflows, and thus different apps

For the purpose of this article, I won’t get into the details and reasons that keep me using Evernote as a central part of my daily workflow; I’d just like to express, again, how I see the Dropbox-based writing and Evernote as two fundamentally separate entities. Stuff like this gets built and researched in Evernote; this very article is being typed in Writing Kit, connected to Dropbox. I’ll get to Evernote in the future, but as a general rule, I think the service is simply fantastic if your research goes beyond just text and hyperlinks, but also includes images, documents, or a combination of both.

Evernote is my memory ecosystem.

Why Dropbox?

When it comes to text notes I like to keep available as a portable file format I own – read: plain text – I use Dropbox. Retaining ownership of my files is important, and Dropbox makes it extremely easy to have a reliable environment of connected apps and services that access the same files and even keep multiple versions of them if anything goes wrong. Furthermore, while Evernote has a solid app on the Mac that keeps getting better on each release, its iOS counterparts are unfortunately lacking when it comes to writing, researching, and multitasking; so while the “longer, research-based” pieces need to be written in Evernote for Mac, all the other articles and shorter posts I produce are better suited for Dropbox. And because for that kind of articles I can (I have to) switch between different apps and devices, I need an open, portable file format that allows me to work from anywhere.

Let David Sparks tell you why plain text equals future-proofing your notes. For me, it’s also about knowing that the text that doesn’t need the “Evernote treatment” can be accessed and edited properly no matter the platform I decide to use. As Brett Terpstra showed in his amazing collection of iTextEditors, there is no lack of Dropbox-enabled apps on the iPhone and iPad.

Goals

In Dropbox, I keep a lot of stuff.

- Article drafts

- Ideas (example: “write a post about your Dropbox workflow”)

- Lists of apps I want to buy

- Lists of apps I need to check out again because they received an update

- Short bits of text (example: email addresses I didn’t have time to enter into Apple’s Phone app)

- Outlines for posts

- A Scratchpad.txt file that I sometimes use as a temporary location for bookmarks I don’t want to bookmark in my browser/Pinboard/Twitter client. Pocket has lessened the need for this file, though.

If I had to cut down the list of main “goals” for my Dropbox-centric writing workflow, I would say these are my requisites:

- Write long form

- Write quick notes

- Make lists and outlines

- Search everything

The tools I use to accomplish these goals are multiple, variegate, and ever-changing; here’s a list of the apps and services I have been using lately to get my writing done.

Dropbox Tools

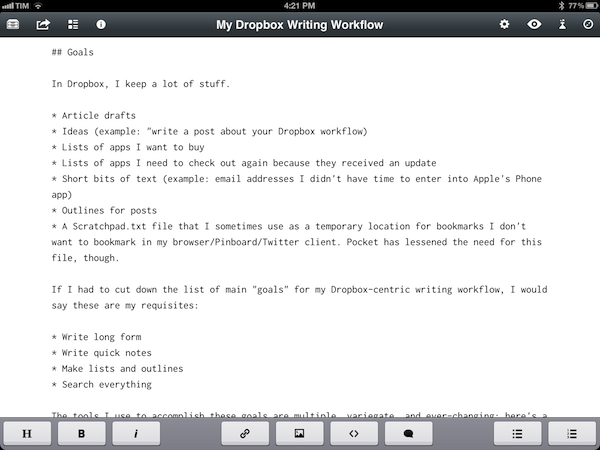

Writing Kit: This is the app that I use (mainly on my iPad) to write articles for MacStories and Ticci.org. As I wrote in my previous coverage of the app:

I, however, am choosing Writing Kit. The reason is simple: Writing Kit does Markdown extremely well, looks good, it’s got Solarized themes, and it combines the writing with powerful research tools. Here’s the thing about Writing Kit: it’s a very niche app that most iOS users looking for a text editor won’t ever need. Even assuming that those who are considering Markdown-enabled apps are, at least to some degree, text nerds, Writing Kit still stands out for being the most complex solution to assemble writing and research. And I mean that in a good way. The app has a browser, a quick research panel, Evernote support, it can convert inline links to reference links, and it happens to have room for a Reading Queue to save webpages for later to reference them in what you’re writing. The amount of options available in Writing Kit is kind of crazy, and I hope this doesn’t evolve into feature creep with time

Writing Kit is powerful. As the name suggests, it’s a “kit”: you can use its single parts as a whole, or focus on the few elements you need without fearing others will get in the way. Here’s a list of facts about Writing Kit that I forgot to mention in my comparison:

- The app works nicely with external Bluetooth keyboards (this week, I am testing the Incase Origami Workstation with an Apple Bluetooth wireless keyboard) as it keeps the extra (and swipable) row of text-related functions available on screen.

- The built-in Markdown cheat sheet can be really handy.

- The Outline popover available in the top toolbar lets you jump to sections and embedded links within your text document.

- I don’t like the way the app names new files with an “Untitled” scheme – I’d rather have the app use a timestamp as its default naming convention, or the first line of a note (as Simplenote does, I believe).

- The built-in browser and dedicated “Link” command for selected text is the best way I have found so far on iOS to quickly and repeatedly bring hyperlinks into a post.

- I really look forward to Writing Kit getting rid of the manual “Sync” button.

Byword: When I am writing articles at my Mac, or simply editing text written on the iPad that needs to be augmented with images and videos before going to WordPress, I like Byword. On the Mac, Byword is a simple text editor meant for writers that don’t like to fiddle with a myriad of settings and options to act on their words. Byword, as the name aptly implies, is focused on words. I like to keep the app in full-screen mode for optimal, true “distraction-free” editing, and I appreciate the subtle formatting that Byword accompanies bold text and hyperlinks with. I know Byword has got a more than decent selection of keyboard shortcuts to do more with text, but as far as my writing workflow is concerned, the priority is on getting the words right, converted to HTML, then posted online.

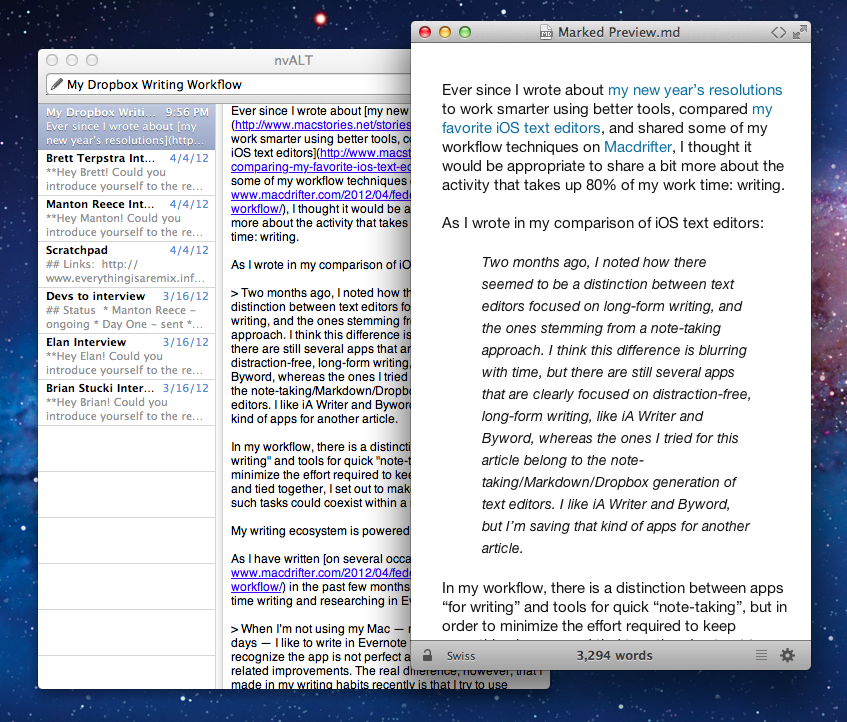

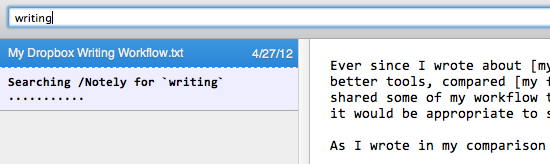

nvALT: On the flip side, when I’m at my Mac and I want to do anything with the text I got into Dropbox, I rely on the most popular fork of Notational Velocity, nvALT by Brett Terpstra and Elastic Threads. Once again, there’s a sea of options, shortcuts, and customization possibilities offered by nvALT that I’m not using. For one, I just recently discovered that I can open any text file fetched by nvALT with a dedicated keyboard shortcut that I can assign to my editor of choice, Byword. Like I said, however, knowing all the options isn’t as nearly as important as knowing that the ones I can use are actually useful. I like nvALT for two reasons: it’s stable and fast, and it blends search with file creation. The latest major release of nvALT really hit the stability point with a series of fixes and improvements that made sure sync with Dropbox is reliable and always up to date.

Obviously, for the sake of my “single ecosystem”, I let nvALT run with single .txt files in a Dropbox directory I specify. And because I am not always at my Mac, but I do have a Mac mini set up with the fine folks at Macminicolo, I let nvALT run all the time on OS X Lion Server, constantly fetching the most recent versions of my notes, backing them up through a Hazel rule to another location on Dropbox for redundancy and security. With this method, I know the Mac mini (which I also use as server for OmniFocus, Plex, Air Video, and other apps) always has my notes in sync with Dropbox, my iOS apps, and the web.

nvALT does a lot of things right (Markdown previews, keyboard shortcuts, minimal UI), but I think the thing it does best is the seamless integration of search and file creation. When I’m looking into my “Notely” folder (I set it up like this when I was trying Notely last year, and never changed its name), I can start searching for a specific note (I don’t use tags), and if no results are returned, I can simply hit Enter to let nvALT create a new note. Found? No problem. Not found? No problem anyway.

Marked: Because I’m an app junkie, I like to try different apps. At this point, discovering new apps from new developers I didn’t know about equals the feeling of discovering new music on iTunes, Rdio, or NME. When it comes to articles I want to publish on the site, I do all my editing in Byword, but sometimes I want to try something different, so I use Brett Terpstra’s Marked utility for the Mac (here’s our review of the latest 1.4 version). Marked is a powerful layer that sits atop your text and enables you to “do stuff” with it. Personally, I like it for the word count and reading stats that Brett built into the app, and for this.

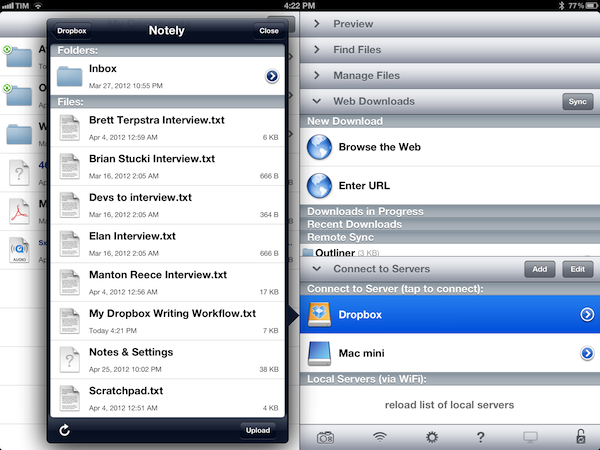

GoodReader: Say what you will about GoodReader – the app is powerful. GoodReader is the most solid third-party file manager currently available on iOS, and, even if not exactly intuitive in some areas, you can stay assured the developers thought about “that option you were looking for”. Among the reasons I use GoodReader for: I can let it “sync” with different Dropbox folders and get text files for me. I have two main Dropbox folders for my text: the aforementioned Notely folder, and “Attachments” (more on this below).

GoodReader can sync with both of them separately, it can display text, and open the .txt files into other apps on my iPhone or iPad. GoodReader is the closest thing to a Finder I have on iOS.

Send To Dropbox: I am not always writing long form content. In fact, most of the time I am simply saving ideas and short sentences in Dropbox. The web service I use to quickly get bits of text as .txt files into Dropbox is Send To Dropbox. Using my “Attachments” folder, Send To Dropbox connects via OAuth to my Dropbox account and gives me a unique email address I can email stuff to. This “stuff” – namely text – is then processed, and saved as plain text into Dropbox within seconds (I did experience some slowdowns in the past year, and those became “minutes”).

Send To Dropbox works with files and various attachments, but I use Evernote for those. For text, you have to make sure a “save as plain text” option is checked in the service’s preferences on the web. You can donate to Send To Dropbox; I wish there was a paid option – even a monthly one – to make me feel good about it.

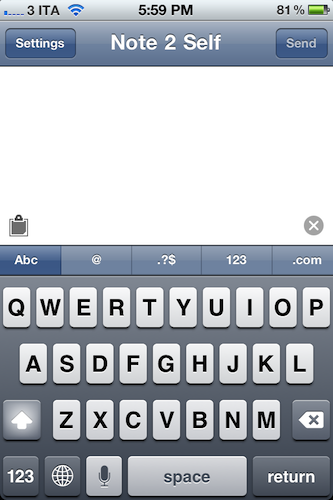

Note 2 Self: So how do I email text to Send To Dropbox? Using Sparrow or Apple’s native Mail framework for iOS is the obvious solution if you’re not willing to tinker with third-party apps. I, however, have been relying on two less-known utilities for the past two years or so: Captio and Note 2 Self.

While I use the former with my Evernote email address, Note 2 Self has always been set up with my Send To Dropbox email address. Both apps allow you to “quickly email” any address, and they use their own web service to forward messages. If you’re scared of possible security implications, Captio lets you configure your own IMAP settings – Note 2 Self doesn’t have this option – but the sending times will then become slower. The benefit of having an app that lets me “archive” a thought in one second (really) outweighs the potential risk of its creators looking at my “remember to buy Notability” and “compare iPad to PC” notes.

Note 2 Self has a nice icon, but it doesn’t run natively on the iPad. In fact, it’s too bad that the developers haven’t been active with the app lately (I assume it’s nothing more than a side project for them). However, the email sending service has been reliable and fast. In the “settings” of the app, you can choose an email address by looking it up in your Contacts. Alternatively, you can write one manually. The same section lets you see how many notes you have queued for delivery, albeit I have always seen a “0” in there. The main area – the compose window – has a few nice tricks to get your text quickly emailed to anyone: there is a button to paste your system clipboard, and an “x” on the left to clear whatever you have written. You can switch between 5 keyboard types with just one tap (perfect for phone numbers), and, unlike other apps, what you write is immediately erased the moment you hit Send.

Note & Share: If, for some reason, I don’t want to save a short text as .txt using Note 2 Self, I can use Note & Share (which I previously reviewed). The app works with Evernote, too, and is capable of saving single .txt files into any Dropbox folder. I prefer Note 2 Self for this task, but it’s nice to have alternatives.

TextDrop: In the past six months, I have been using my iPad a lot more. For as much as I make an effort to rethink my PC-era computing habits around the advantages of the iPad, there are just some things that need to be done on my MacBook Air. Don’t get me wrong, I love my MacBook Air, but it appears to me much of the innovation among indie developers has been happening around the iOS platform lately. And because when I’m at my Mac I’m typically editing in Byword or getting lost inside Google Chrome tabs, many times I wished there was a simple solution to access my entire Dropbox through the browser to edit .txt files with it. Dropbox should figure out a way to at least let users modify plain text from the web interface.

Thanks to Macdrifter’s recommendation, I was pointed to TextDrop, a simple web app that lets you navigate your entire Dropbox and edit text within the browser. It supports folders and sub-folders, has got a basic Markdown preview functionality, sync status indicators, and, more importantly, it lets you bookmark folders or single notes with their own filename. So, for instance, I can have a bookmark in my browser’s toolbar for /Dropbox/Scratchpad.txt that I can open with a single click (or keyboard shortcut with Alfred) to drop links and other random text that I’ll process later.

I like TextDrop for its simplicity. It’s not a text editor: it’s a web interface for Dropbox, tailored for text. Right now, subscribing is only $5 per year, and if I had to pick two features I’d like to see implemented they would be: a “shelf” for most-accessed notes, and support for emailing text to your TextDrop account.

Outliner: Articles don’t always start as a cascade of text written in a single session. Sometimes I like to make an outline of my articles, and I also like to let that outline simmer for a few days until I’m happy with the ideas and points I have collected. To keep such text-based outlines that I can edit and re-adjust at any time, I use CarbonFin Outliner: it is the best iOS outliner that syncs with Dropbox (aside from its own web app), which means I can easily store outlines alongside my notes, and transform its OPML files into plain text documents using OmniOutliner or other utilities. If I want, I can even create a mind map with iThoughts or MindNode off that OPML file to better visualize the concepts I’m working on. Or, as I do most of my writing on the iPad anyway, I can simply copy the outline in Outliner using the “copy all” command, and paste it in Writing Kit to start writing. Outliner is a great app; I wish The Omni Group considered Dropbox as a native option for their apps.

TaskAgent: Last, I like to keep lists inside my Dropbox and alongside my notes. An evolution of the Todo.txt method I previously mentioned on MacStories, I switched to TaskAgent because I like its fast-release cycle and the features Francisco Cantu is considering for the future. Starting from a simple, text-based and simply-formatted list, TaskAgent gives me a nice interface that makes it easy to enter and manage items. The item creation dialog could use some UI refinements; I like how it lets you quickly enter items one after the other though.

In TaskAgent, I keep lists of apps I want to buy or update, and lists of stories I want to work on. These lists can be archived and retrieved later, and they exist as standalone .txt files in my Dropbox. If I want, I can add items to my lists using TextDrop, GoodReader, or TextEdit on my Mac; I guess it’d be nice to have a dedicated TaskAgent Mac app with the possibility of entering items with keyboard shortcuts.

TaskAgent doesn’t just prettify text lists, it makes them more accessible and easier to manage. And, because it’s plain text, I can copy a list, turn it to Outliner, elaborate on it, and make it evolve into an article using my text editor of choice. It’s a connected process.

Just A Folder

In thinking about a proper conclusion for this post, it occurred to me that the best way to sum up the possibilities offered by Dropbox to writers and note-takers is this: with just a folder, you can fine-tune your workflow using the apps you prefer. It’s a liberating effect: the text is there, and it will be there no matter how many apps you try or how much you tinker. Ultimately, it just comes down to writing.

Dropbox has become my inbox for text.