There’s been a lot of discussion in the past few days over Apple, its In-App Purchase (IAP) policy, and Dropbox after it rejected a few apps that employed Dropbox functionality because they offered links to the Dropbox website for signing up and logging in. At issue was that the option to buy a higher level of storage was also visible, and this contravened one of the App Store Review Guidelines. Some viewed this as Apple trying to kill (or at the very least, target) Dropbox – but as Federico explained, this was just Apple enforcing one of their existing policies.

After thinking about it for a while, I’ve come to the position that perhaps that policy isn’t the right one. So I decided to play the devil’s advocate, and try to argue the case for Apple adjusting their policy. Specifically my argument focuses on Apple’s policy going something like:

Apps may use external mechanisms for purchases or subscriptions to be used in an app, but only when those purchase mechanisms are undertaken in a web view within the app.

That could probably be further clarified in more simplistic language, but you get the general idea of what I’m proposing. The current policy prohibits any link to purchases or subscriptions that are undertaken through external mechanisms (ie. not IAP); I suggest that this should be allowed. So let’s quickly go through the benefits of the current policy and arguments for relaxing the policy.

Benefits of the current policy

- Security for users (all purchases done through Apple).

- Additional revenue stream.

- Consistency & simplicity for purchases.

Reasons for relaxing the policy

- It does customers a disservice.

- Some of the applications of this rule make Apple seem petty.

- The revenue stream is relatively inconsequential.

- It wouldn’t be any more inconsistent than the rule already is.

- Every time another app gets rejected, there is some level of backlash from media and consumers.

- Might give weight to any anti-trust investigation.

It does customers a disservice

One of the primary reasons in favor of having the 30% rule is that it promotes not only simplicity (the process for In-App Purchases is standardized and somewhat familiar to customers), but also safety because the IAPs are handled by Apple. Ben Brooks has an article defending the rule by arguing this very point quite thoroughly, and it certainly is a strong argument.

The Kindle Example

But doing it this way has consequences, and I’m not sure that the safety and security benefits outweigh them. Perhaps the biggest inconvenience is illustrated perfectly by what happened to the Kindle app when Apple last year settled on what to do about buying content inside an app. As Apple began to enforce its rule, many such as Amazon had to modify their apps to remove all references and options to pay using a web browser/non-IAP method. For Amazon, this meant removing the “Store” button in the Kindle iOS apps.

This effectively meant that the Kindle app got a significant downgrade when Apple began enforcing the rule. I should note that Amazon could have kept the store in the app if they used IAP, but it would mean that 30% of sales would go to Apple and because e-books are now sold using the Agency Model (I explained this and the DOJ complaint against Apple and the big publishers in a recent article), Amazon would get no revenue because their cut is also 30% (ie. Apple has already eaten Amazon’s slice of the pie). Also due to the agency model, Amazon couldn’t just raise e-book prices to offset Apple’s cut, because in the agency model, it is the publishers who set retail prices – not Amazon. Plus, even if they could do that, making iOS customers pay more for the same e-book so both Apple and Amazon get their 30% cut is a terrible trade-off for consumers. So, Amazon had to either remove the purchase options from their apps or face selling e-books with zero margin.

The Rdio Example

Alternatively we could look at Rdio, the music service that many of you are familiar with. The enforcement of Apple’s rule also meant that they faced a terrible trade-off:

- Use IAP for signing up new users to the subscription and receive 30% less revenue from iOS users (because Apple takes their standard 30%)

- Use IAP for signing up new users to the subscription, but charge more to cover the cost of Apple taking 30%

- Make the app purely for existing subscribers, don’t give users the option to subscribe from the app

Rdio (likely) couldn’t possibly choose the first option with all the licensing contracts with music publishers/labels. The last option is terrible because it would be turning away all users who discover Rdio through the App Store (a sizable proportion I’d presume). So Rdio chose to charge a higher subscription fee when paying via IAP in order to maintain the subscription fee after Apple has taken their 30% out – people who subscribe through the Rdio website get to pay less.

The Thumbtack Example

As a third example, I’m going to use Thumbtack (disclaimer: Don Southard, fellow MacStories writer, is the developer of the app). In one build that he submitted for approval, the login page linked to Pinboard to create a new account. It was rejected because Pinboard is a paid service that must be purchased. This is perhaps most similar to the recent spate of rejections that afflicted various apps that employed the use of Dropbox and linked to sign-up pages that also gave the option to purchase a higher level of Dropbox storage.

I’d also like to quickly touch on the security argument, as I have some issues with putting so much weight on it. Sure, there is some comfort in knowing that Apple is dealing with your credit card when you purchase an app or IAP and not some unknown developer. That point shouldn’t be dismissed, but online purchasing is not a new thing: people do it every day from their computers, iPads and iPhones, and often with a relatively unknown company, and by and large people don’t face any issues with this.

As for the issue that Apple would get blamed if an app was malicious – all it takes is for Apple to pull the app (and remember, Apple has a lot of information about the developer it can forward to police authorities).

The revenue stream is inconsequential

This is pretty straightforward: I don’t think Apple would lose much money at all if it relaxed the rule. IAPs through Apple’s purchase mechanism wouldn’t even be significantly affected by the relaxation of the rule either – because it would mostly be facilitating purchases that wouldn’t have happened in the first place (the Kindle Store). Perhaps the only example in which Apple would “lose” money is for those in which the developer chose the Rdio path, raising IAP prices to cover for the lost 30% to Apple – and I doubt those are significant in any way to Apple. Let’s not forget that to some degree, Apple has already ceded some revenue to newspapers and magazines, which allow print subscribers to access content for free that would otherwise be sold through IAP.

Then, to ensure that IAP isn’t replaced on a wide scale by developers, the simple of restriction of requiring third party purchase mechanisms only work through a Safari web-view via an actual website should keep most developers sticking to IAPs.

It wouldn’t be any more inconsistent than the rule already is

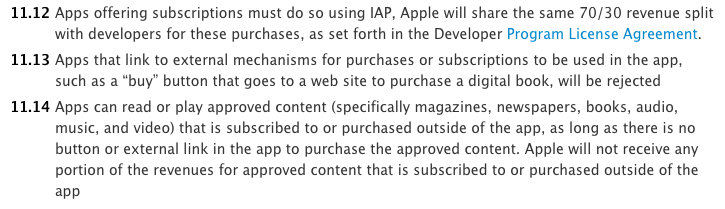

If you’ve been following the controversy over IAPs and subscriptions, you know that this is something that Apple has had some difficulty in getting “right”. Last year saw a number of flip-flops over IAP subscriptions, and at times it was incredibly confusing and for developers affected the uncertainty was disconcerting. The image at the top of the post outlines the current policy, but throughout last year there were periods in which the following was true:

- Print subscribers to newspapers/magazines were not allowed free access to content being sold through IAP (presumably because it got around Apple’s 30% requirement).

- If content was offered outside of IAP, it had to be offered on IAP also and at the same price.

- Apps could link to third-party stores for the purchase of content or subscriptions (i.e. Kindle Store).

So as you may deduce, the rules started off fairly lax (dot point 3), but when Apple announced their new policy it was a lot stricter. Pressure was put on Apple over weeks and months and slowly but surely Apple caved in to various demands until they got to the current policy. Playing devil’s advocate today, I’m arguing they should bend the policy just a little bit more, for the benefit of consumers.

Every time another app gets rejected, there is some level of backlash from media and consumers

Why am I writing this article this week? Well, I’m writing about it because we’ve recently had a round of articles spread across the blogosphere after Apple rejected some apps that were using Dropbox as described earlier. In particular, there was a lot of backlash and criticism over the issue and this happens every time Apple gets strict again and enforces a rule that they may have become lax in enforcing. Partly, this is the media’s fault for exaggerating the entire issue, but I think we at MacStories have been careful at analysing the issue carefully, and Federico rightly straightened out some theories about Apple trying to kill Dropbox. I may be taking advantage of the media storm over the issue because I am writing about this today, but at the same time I felt myself thinking about the issue and it got to the point where I felt it was necessary to put words to paper.

Getting back on track, I don’t think this factor alone would be enough to get Apple to alter their policy: they rarely react to such media criticism and are happy to just bear through the criticism until either people are sick of hearing about the issue, or they have convinced people it is the right policy (App Store apps requiring approval is a classic example here). But it is a negative and I think perhaps combined with the other factors, Apple has more to gain by changing the policy rather than sticking to their guns on this issue.

Might give weight to any anti-trust investigation

Maybe it’s completely ridiculous for me to bring this up, but I don’t find it impossible to foresee a day when Apple is (rightly or wrongly) facing a serious anti-trust investigation. A policy like the one described here might not have a huge impact, but it is certainly one that could be used to paint Apple in a negative light. Just look at the Kindle example: Apple has effectively forced Kindle to remove the option for users to purchase more books from within the app – I don’t think it was their direct intention, but that doesn’t take away from the fact that Apple’s policy had that effect. What happens if Apple launches a subscription music service to rival Rdio – Rdio will be at an instant disadvantage on the iOS platform because unless new users know about the cheaper prices on their website, Rdio’s service will (likely) be more expensive. These kinds of arguments could go on and on; personally, I don’t think they are very convincing in the anti-trust field, but I certainly think it is something that Apple should potentially be wary of going forward. Particularly so, given the fact that antitrust enforcers last year “looked” at Apple’s IAP subscription policy whilst it was in the period of turbulence and change.