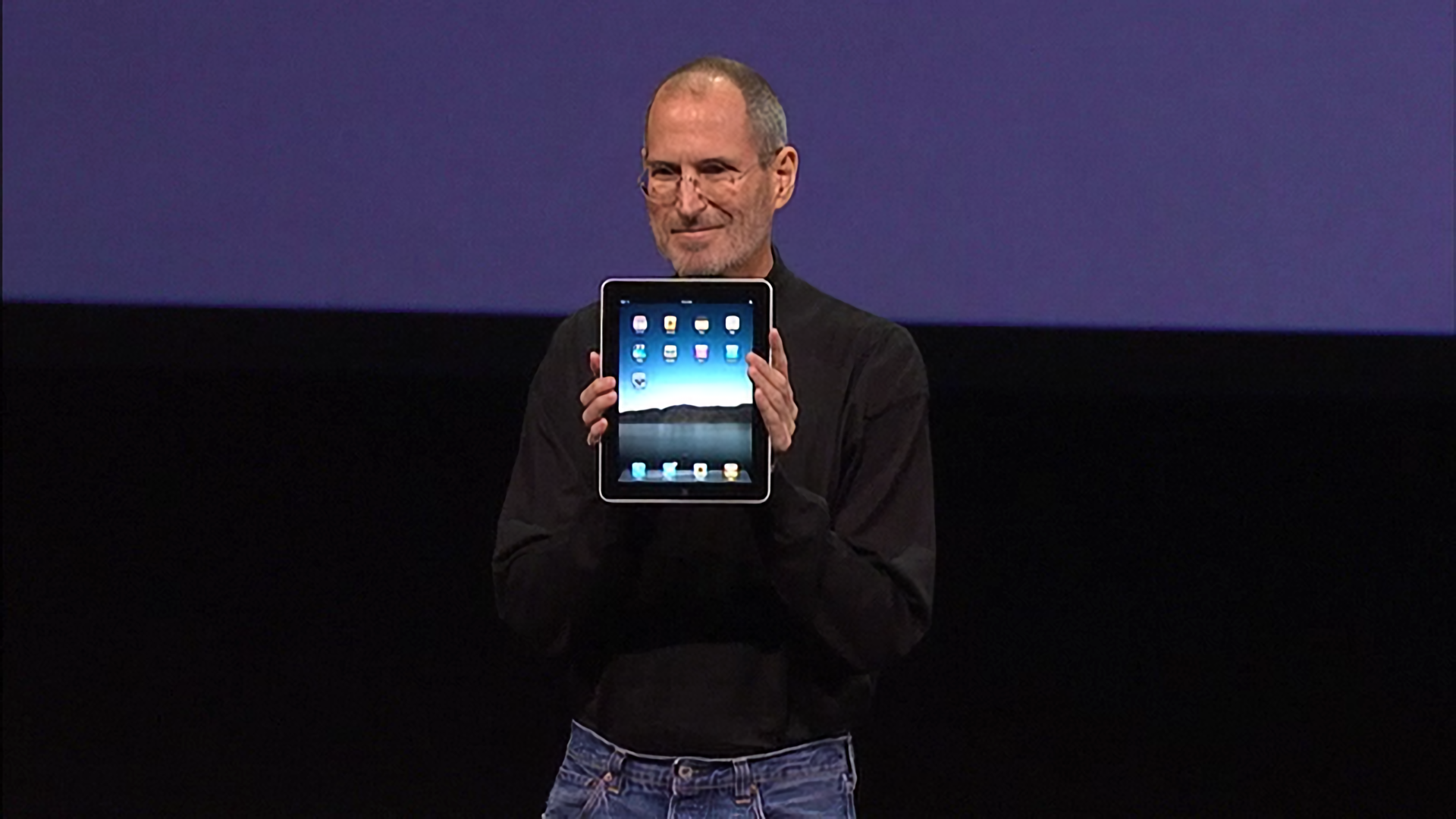

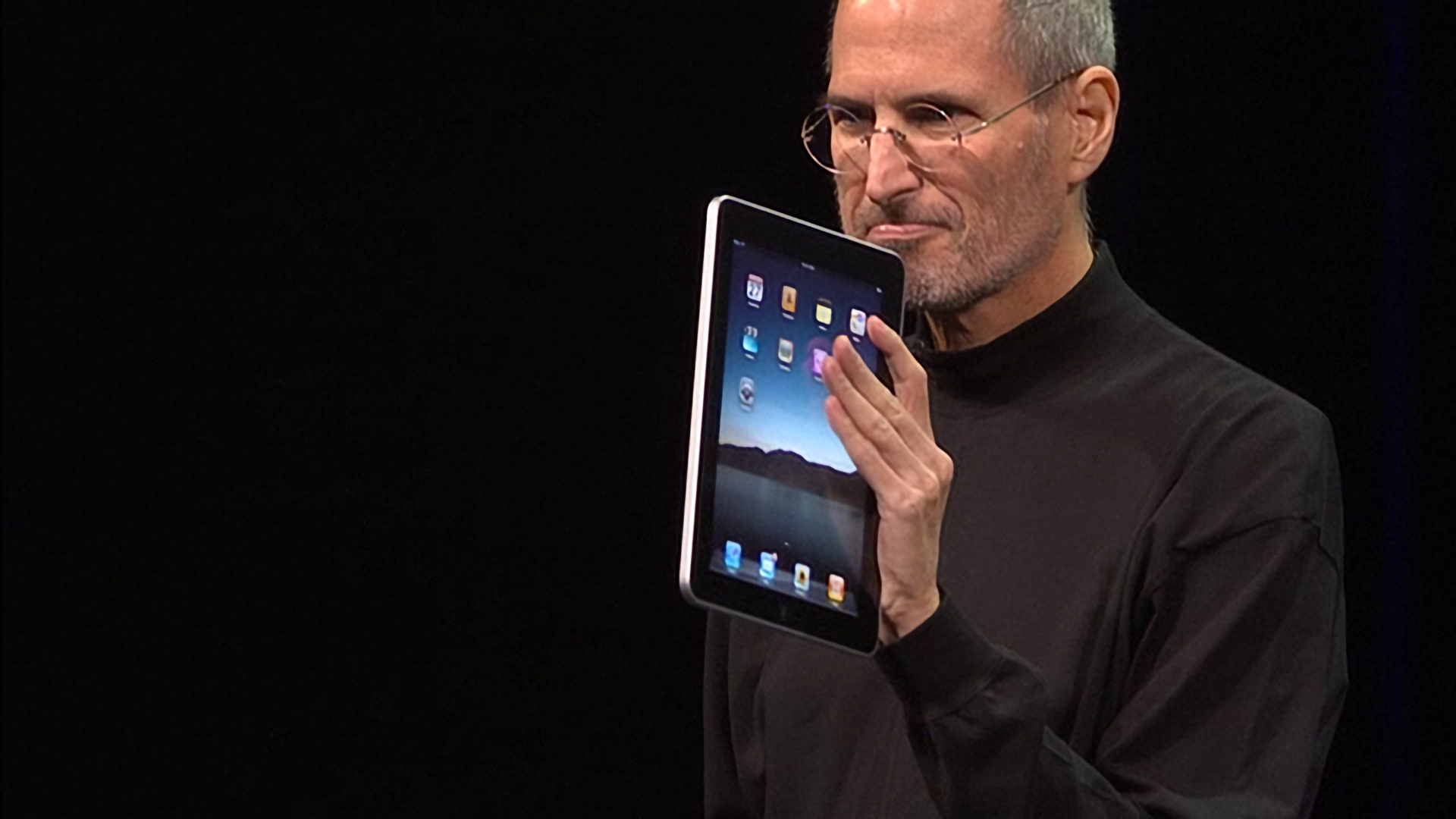

When Steve Jobs strode onto the stage at the Yerba Buena Center on January 27, 2010, he carried with him the answers to years of speculation and rumors about an Apple tablet. Everyone at the event that day knew why they were there and what would be announced. Jobs acknowledged as much up front, saying that he had a ‘truly magical and revolutionary product’ to announce.

Thanks to the iPhone, everyone at the Yerba Buena Center also had a vague notion of what Apple’s tablet would probably look like. Mockups and phony leaks were all over the web, and tablets weren’t new. Everyone expected a big slab of glass. Beyond that, though, few rumors were in agreement about what the tablet’s hardware specs would be.

It was correctly assumed that Apple’s tablet would fit somewhere in between an iPhone and a Mac both physically and functionally, but where exactly was a mystery. That made the OS and the apps the stars of the keynote and critical to the way Apple’s tablet would be used and how it would be perceived for years to come.

Before Steve Jobs revealed Apple’s new tablet to the world, though, he paused – as is still customary during most Apple keynotes – to set the stage and provide context, which is where I will start too. Ten years ago, the tech world was a very different place, and Apple was a very different company. Not only is it fun to remember what those days were like, but it helps explain the trajectory of the iPad in the decade that followed.

The Rumor Mill

Rumors that Apple was working on a tablet device circulated for years before the iPad was released in 2010. According to an Engadget story published the day before the iPad was revealed, tablet rumors stretched back to at least the early 2000s.

It wasn’t until the iPhone was released in 2007 that the rumors really picked up in earnest, though. At the time, a small army of bloggers covering Apple competed for scoops by combing through patent filings, domain registrations, and any other scrap they could get their hands on, looking for evidence of a tablet. It was the waning days of the ‘golden age’ of Apple rumors, before Apple ‘doubled down on secrecy.’ The same competition that fueled the rumor mill led to a cottage industry in device mockups that sometimes got passed off as ‘spy shots’ of real hardware.

It was an environment that fed on itself, spawning crazy speculation. The rumors and mockups may seem like unimportant historical relics now, but they’re still instructive in understanding the expectations going into the iPad’s launch and a lot of fun to revisit. Here is a collection of some of my favorites:1

Source: digitaltrends.com.

Source: digitaltrends.com.

Source: digitaltrends.com.

Source: digitaltrends.com.

Source: Chris Messina, factoryjoe.com.

Source: Chris Messina, factoryjoe.com.

Source: Chris Messina, factoryjoe.com.

Source: Chris Messina, factoryjoe.com.

Source: obamapacman.com.

Source: stereopoly.de.

Source: gizmodo.com.

Source: chillix.wordpress.com.

Source: chillix.wordpress.com.

Source: thenextweb.com.

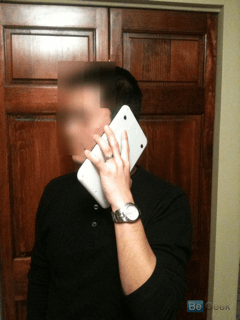

Source: BeGeek via thenextweb.com.

Looking back at these mockups, what strikes me is how many imagined a tablet that would run OS X. Over and over, the mockups envisioned a windowed environment with a Mac-like UI. Even though the iPhone had been out for over two years, surprisingly few mockups approached the design with the iPhone as their starting point. Instead, it was assumed that a tablet with a screen closer to the size of a Mac would naturally inherit the Mac’s OS too. Surely a device with room for windows would run something more than just iPhone OS.

The assumption that an Apple tablet would run OS X may be part of what drove rumors that it would carry a Mac-like price tag of around $1,000 too. It’s long been suspected that Apple planted the notion that the iPad would cost that much with a story that appeared in The Wall Street Journal just over three weeks before the iPad was announced. I’m not sure that’s the case, though.

The Wall Street Journal was quoting an analyst report from a month earlier. Also, sifting through the many rumors leading up the event, there were many guesses of a price in the neighborhood of $1,000 that were made long before the announcement. Not all guesses were as high as The Wall Street Journal’s report, but none were as low as the $499 price point Apple announced either. Whatever the explanation, attendees that winter day in San Francisco expected an expensive slab of glass.

Beyond the walls of Apple’s Cupertino headquarters, the tech trend that hung over the iPad event more than anything else was the rise of the netbook, an inexpensive laptop that relied primarily on web apps. In 2010, the US and much of the rest of the world was just emerging from a severe recession, and at an average price of $300-$500, netbooks were attractive to a lot of consumers.

On an earnings call the year before the iPad was announced, Tim Cook, who was serving as acting-CEO at the time, said in response to an analyst question about when Apple would have an answer to netbooks:

We’ve got some ideas, but right now we think the products there are inferior and will not provide the experience to customers that they’re happy with.

Jobs had delivered essentially the same message in the fall of 2008 and suggested that, for the time being, the iPhone was Apple’s answer to netbooks.

Warming Up the Crowd

Steve Jobs loped onto the stage on January 27th, 2010 with Apple’s answer to netbooks. However, he began the event by launching into one of his signature updates on Apple’s recent accomplishments. He touted the 250 millionth iPod sold, and mentioned the still relatively new iPhone 3GS, but most relevant to the day’s announcement was the 18-month-old App Store.

After only 18 months, there were 140,000 apps on the App Store that customers had downloaded over three billion times.

At the time, the App Store already offered 140,000 iPhone apps. That number seems tiny compared to today when there are over two million apps available, but even at that level, the Store had become a legitimate cultural phenomenon that had captured the imagination of people around the world, as demonstrated by the fact that a total of over three billion apps had been downloaded in just 18 months.

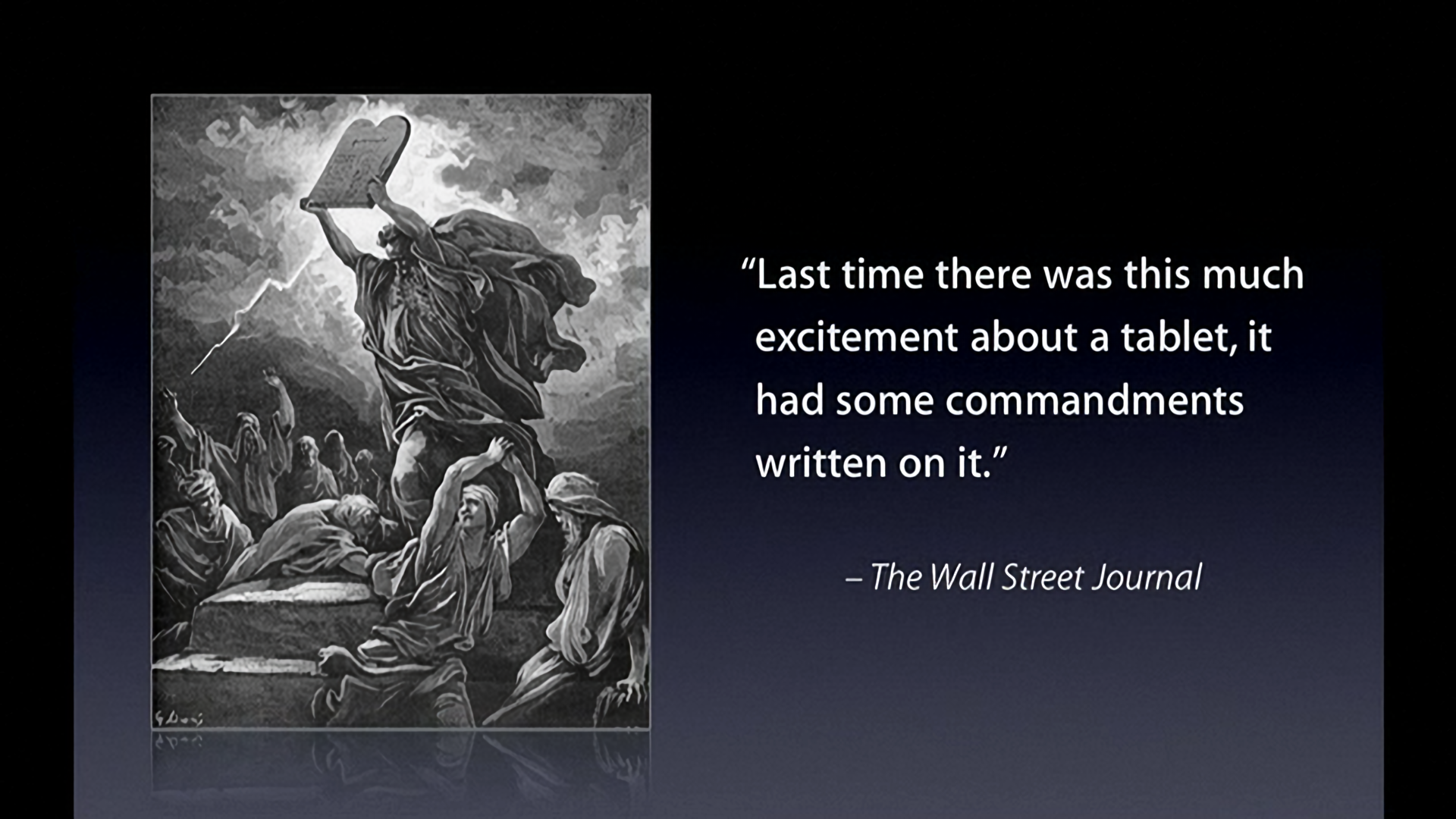

As Jobs wrapped up his overview of Apple’s achievements, he acknowledged the incredible expectations and pressure on the company that day by referencing a recent story from The Wall Street Journal:

Last time there was this much excitement about a tablet, it had some commandments written on it.

Behind Jobs was a slide of Moses returning from Mount Sinai with the Ten Commandments. The joke landed well, simultaneously acknowledging the importance of the event for Apple and warming up the crowd. I only wish Jobs had used this image I ran across in my research instead:

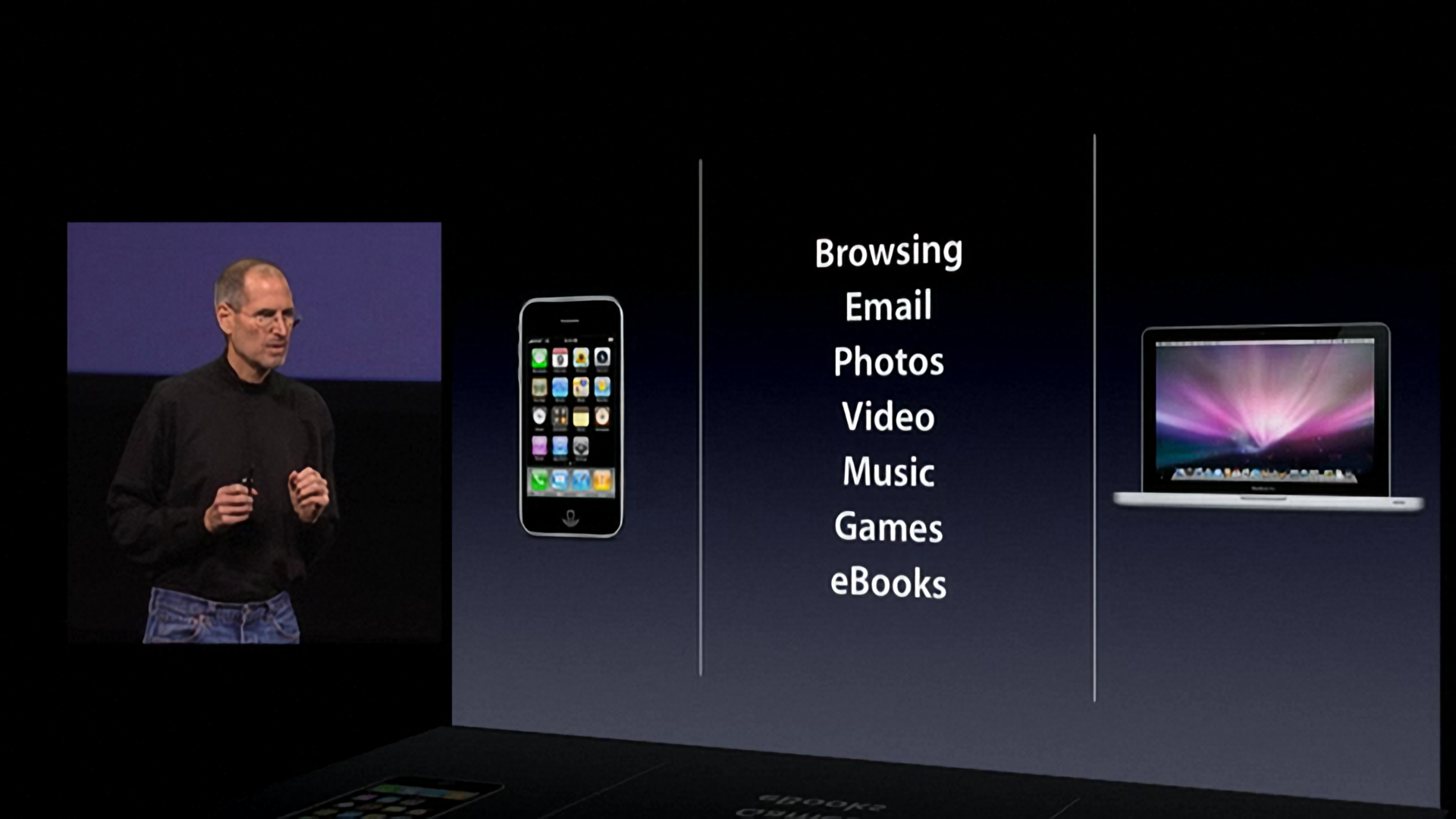

With the crowd ready to start, Jobs launched into his pitch, asking rhetorically whether there was room for a device that sits between the mobile phone and laptop. Of course, the answer was ‘yes,’ but only if, as Jobs explained, the device was ‘far better at some key things.’ Those things were:

- Web browsing

- Photos

- Video

- Music

- Games

- eBooks

Before revealing Apple’s answer to what was suited to these tasks, Jobs set up and knocked down the netbook, declaring that ‘the problem is, netbooks aren’t better at anything…they’re just cheap laptops.’

As the crowd was still chuckling over Jobs’ swipe at netbooks, he explained that Apple had an answer to the third category of device: the iPad. The device took over the screen behind Jobs as he walked over to a small table sitting next to a stylish black leather chair with a chrome frame.2 Underneath a cloth on the table was an iPad. Jobs picked the iPad up and proudly displayed it to the assembled crowd.

Jobs paced the stage quickly, running through each of the categories of tasks he’d outlined previously with a short overview of the core iPad apps from Apple running on the familiar iPhone OS. With the preamble and reveal out of the way just 12 minutes into the one hour and 45-minute keynote, Jobs walked over to the chair waiting for him onstage, sat down, and unlocked his iPad.

It was demo time.

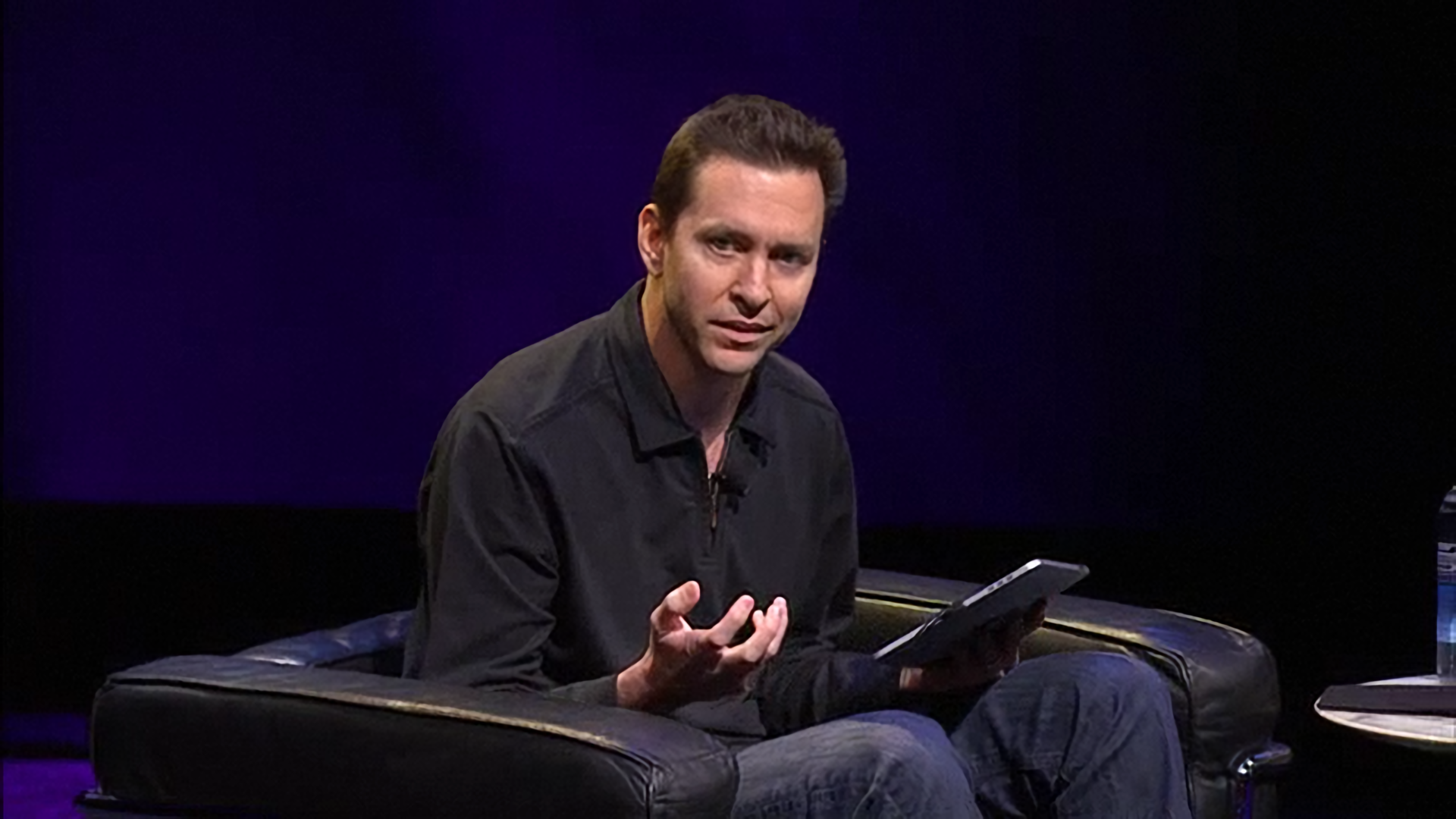

More Intimate Than a Laptop and More Capable Than a Smartphone

The remainder of the keynote was dedicated almost exclusively to demos. Demos are a staple of Apple events, but the iPad’s introduction was unique for the amount of time that Jobs, Scott Forstall, and Phil Schiller spent walking the crowd through app after app. Jobs made the case that out of the box, an iPad justified the creation of a third category of device because it was better at the core experiences he had listed at the top of the presentation. Forstall’s job was to get developers fired up and show off early third-party apps. Schiller wrapped up with the new iWork suite for the iPad, which suggested what the future might hold for the device.

When Jobs sat down, he immediately launched into a demo of Safari. Suddenly, the ‘Safari Pad’ rumors from 2007 made sense as Jobs repeatedly emphasized the power of holding the Internet in your hands as he browsed The New York Times3 and other websites. It was the perfect way to lead off the demos too, combining the intimacy of the iPhone’s touch UI with a big, bright display reminiscent of a laptop.

As I rewatched Jobs make his way through apps like Safari, Mail, Videos, YouTube, and iPod, a couple of things struck me. One was that he rotated the iPad a lot. Jobs showed off reading an email message in portrait orientation then rotated the iPad to see his list of messages on the left with a preview on the right. He took similar approaches with Safari, Photos, the iTunes Store, and iBooks.

The message was that the iPad could become whatever users wanted it to be through its apps. Jony Ive reinforced that in the event’s closing video, declaring that the iPad was defined by its single slab of multitouch glass and lack of an input device or prescribed orientation. Nobody rotates their iPad as much as was demonstrated onstage, but Apple was sending an unmistakable message that the iPad was designed to disappear beneath users’ fingertips the same way an iPhone does, but deliver the computing power to drive a big display.

That all three presenters conducted their demos leaning back in that black leather chair was part of the message too. John Gruber put his finger on one aspect of the chair’s import following the introduction of the iPad 2 in 2011:

The on-stage demos of the iPad aren’t conducted at a table or a lectern. They’re conducted sitting in an armchair. That conveys something about the feel of the iPad before its screen is even turned on. Comfortable, emotional, simple, elegant. How it feels is the entirety of the iPad’s appeal.

It’s that unique and very personal feel that sets the iPad apart from a laptop, where users are separated from the apps they use by an intermediary pointing device.

But there’s more to the chair than that. With the exception of email, the list of activities that Steve Jobs said the iPad had to be better at are largely content consumption activities. Like watching TV, those sorts of activities lend themselves to a lean-back experience sitting in a comfortable chair to browse webpages and photos, watch videos, listen to music, play games, or read a book. The iPad is undeniably an excellent choice for those activities, but by focusing on them up front and largely to the exclusion of more creation-based tasks, Apple defined the iPad as a content consumption device, a reputation that stuck for years thereafter. Jobs’ comfortable black chair may have worked to convey the intimacy of interacting with an iPad, but it also held the iPad back.

Leading up to the iPad keynote, there were as many fanciful mockups of an Apple tablet that looked like a Mac as there were ones that looked like an iPhone. With the emphasis on media consumption apps and the tight coupling of iPad and iPhone app development, those early notions of a more laptop-like productivity tablet were largely swept away. They weren’t completely abandoned, as Phil Schiller’s introduction of iWork for the iPad would demonstrate, but the emphasis was clear: in the space between the iPhone and Mac, the iPad sat closer to the iPhone’s end of the spectrum than the Mac’s.

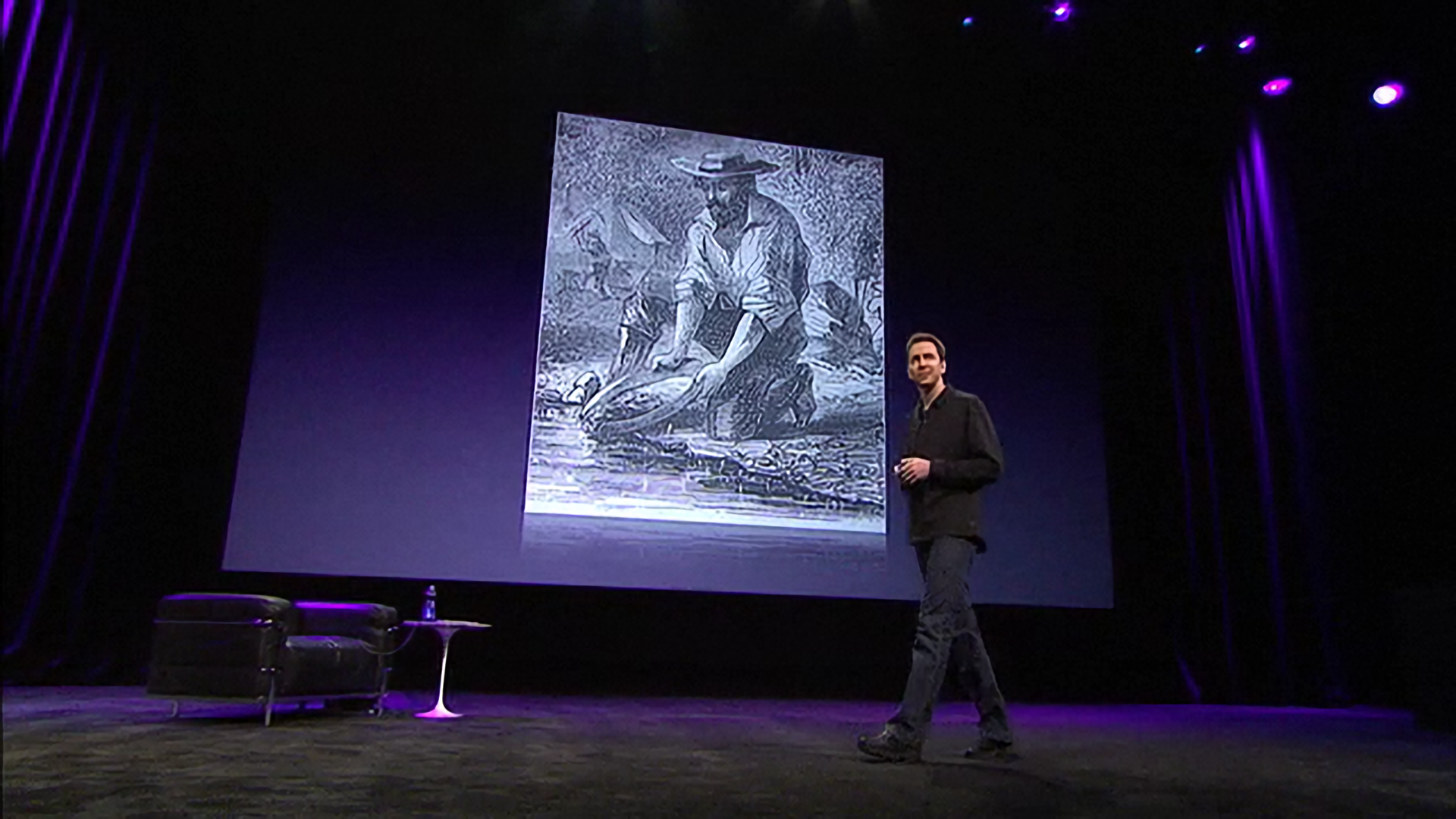

That message was reinforced by Scott Forstall’s segment of the presentation. He bounded onto the stage full of excitement, clearly tasked with getting developers on board to make iPad apps in the short two months between the keynote and launch of the iPad. That was a tall order, especially since developers would have to start building apps without the hardware on which to test them.4

In hindsight, it’s clear that Apple was concerned about whether developers would make apps for the iPad. Forstall laid it on thick in his presentation, promising a ‘second gold rush’ on the App Store driven by iPad apps, flashing a slide of a gold prospector on the screen behind him. That was followed by a parade of third-party developers who showed off games5 like N.O.V.A. and Need for Speed, and apps like Brushes, The New York Times,6 and MLB at Bat.

Apple added iPad-specific development tools as part of the iPhone SDK, but it also hedged its bets with compatibility mode, allowing apps to run at their native size surrounded by a sea of black or blown up to twice their normal size. The experience wasn’t great, but it filled the gap until iPad versions of popular apps were ready.7

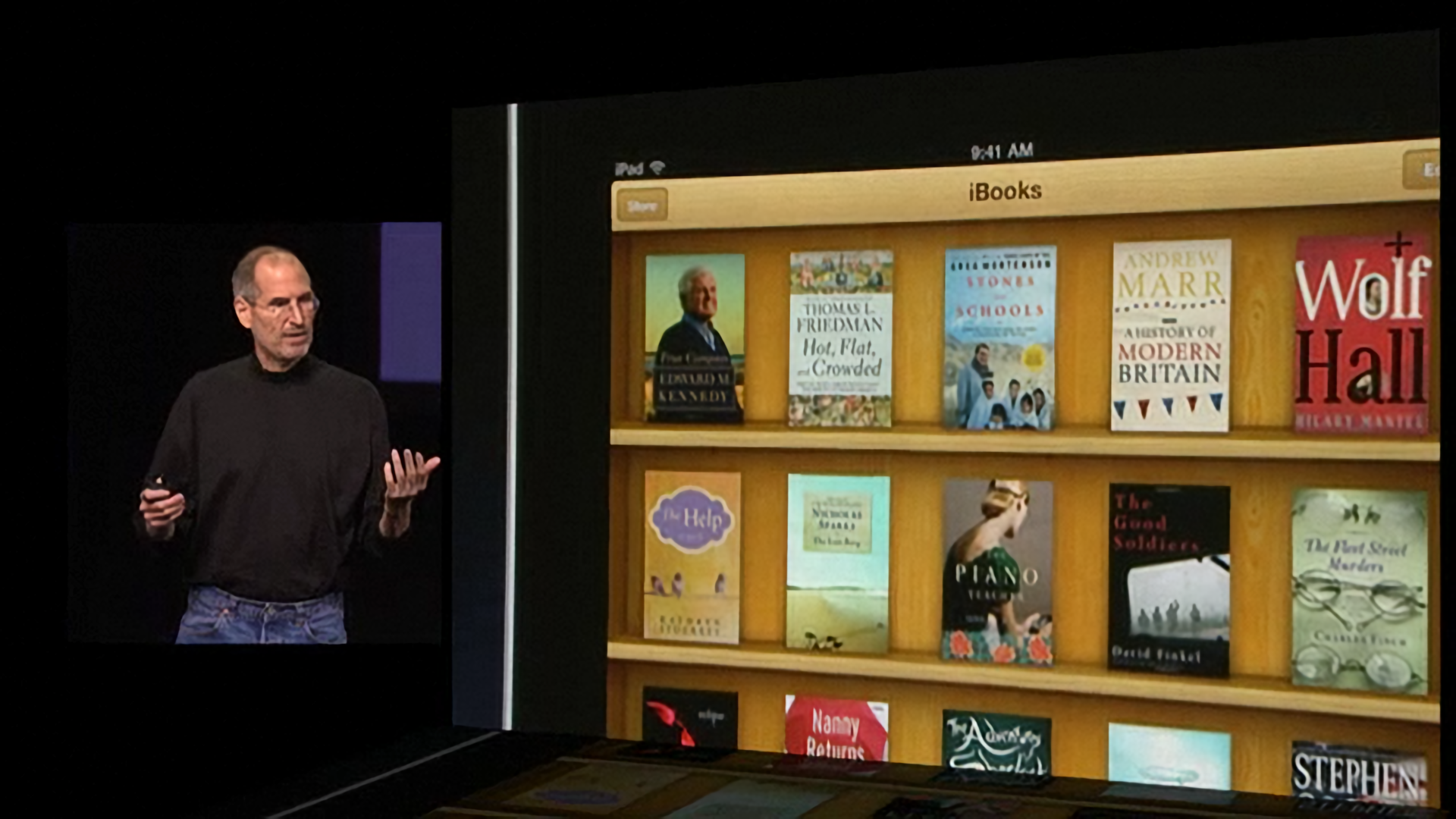

The final segment of the keynote was reserved for all-new Apple apps. Jobs returned to the stage to introduce iBooks. It’s fun to rewatch this part of the keynote because it’s a great example of the skeuomorphic design that was taking an ever-increasing hold on Apple’s mobile devices. The app featured a wooden bookshelf that spun around when you tapped the ‘Store’ button in the toolbar, which Jobs described as ‘kind of like a secret passageway.’

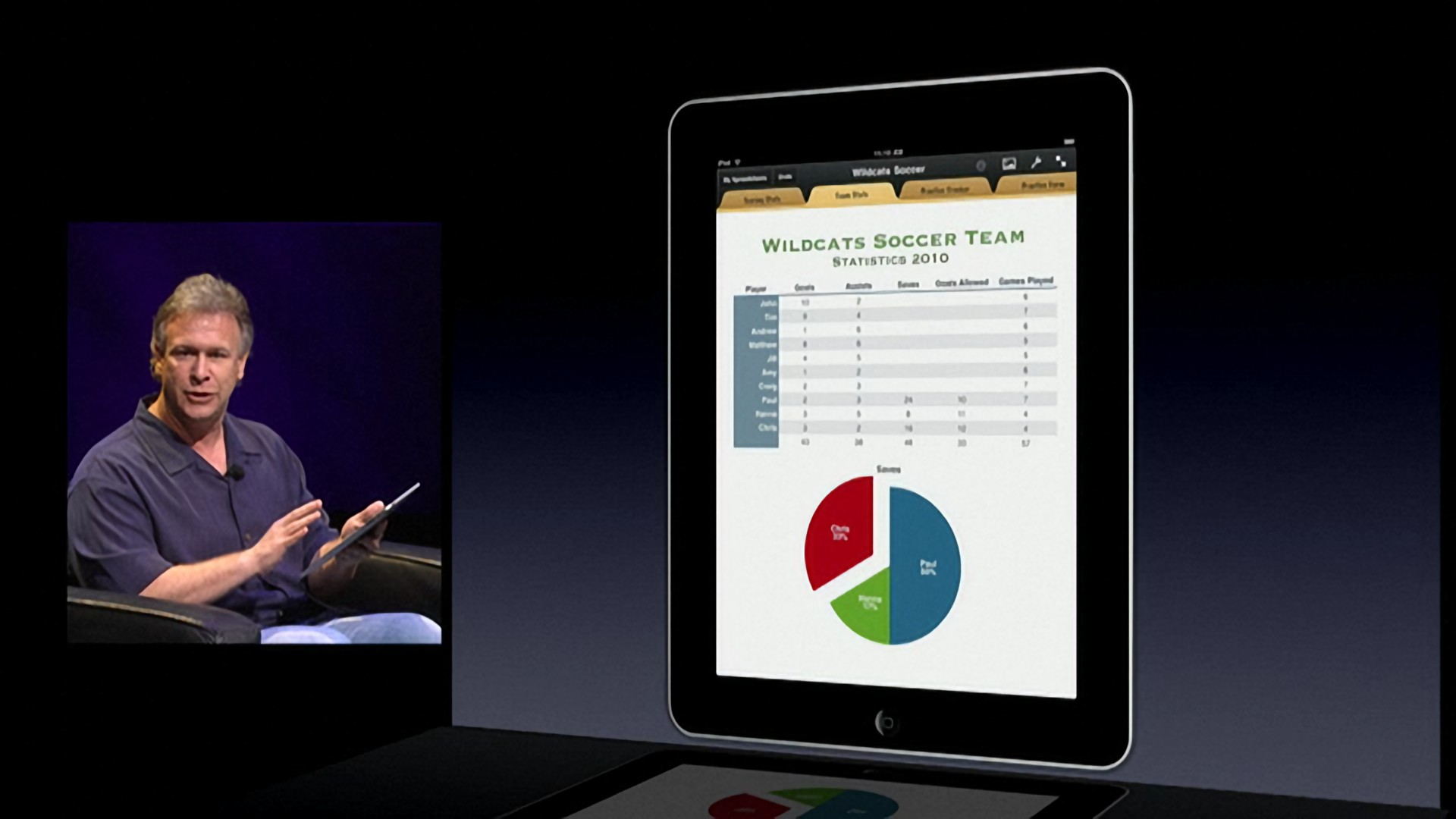

To wrap things up, Phil Schiller demoed iWork for the iPad, which was an interesting departure from the consumption-heavy apps spotlighted during the rest of the keynote. Schiller walked the audience through Pages, Keynote, and Numbers, showing off impressive adaptations of the apps that, until then, were only available on the Mac. There wasn’t complete feature parity between the Mac and iPad versions of the iWork apps, but Schiller’s demo hinted at the possibility of a more productivity-oriented future for the iPad.

The inclusion of iWork at the end of the presentation feels like another hedged bet in hindsight. The excitement of the participants in the keynote was unmistakable. Apple knew it had created something special, but it wasn’t entirely sure how people would use it. The company seemed to be placing most of its bets on consumption apps, but with iWork and the somewhat odd portrait-mode keyboard dock, Apple wanted to be ready if customers gravitated toward more productivity-oriented uses too. Having emphasized the consumption aspects of the iPad so strongly, though, the identity of the iPad’s first era was all but inevitable.

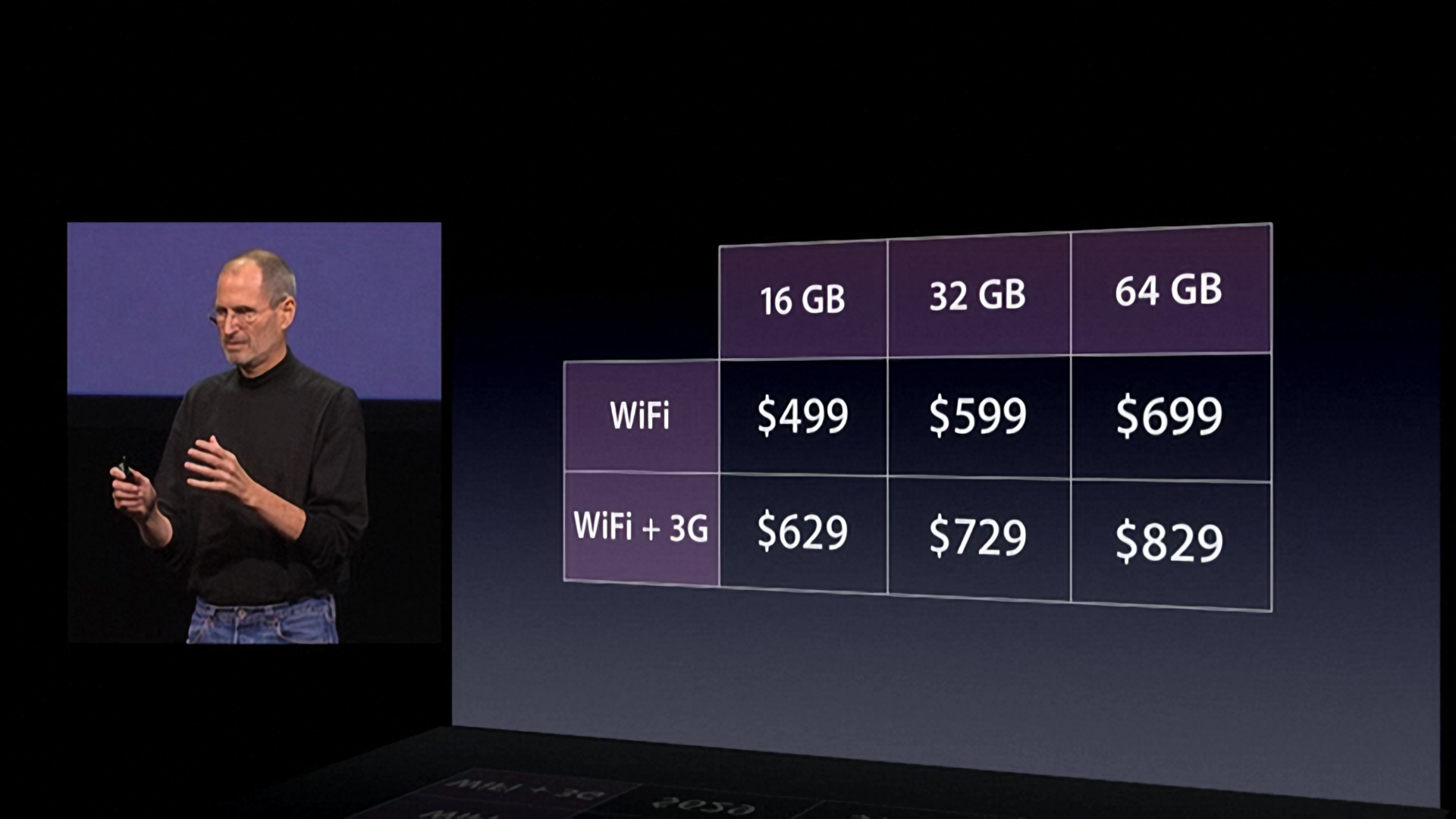

The final surprise of the iPad event was its price. The conventional wisdom was that the device would cost in the neighborhood of $1,000. When the 16GB WiFi model was announced at $499, the crowd was shocked. With more storage and 3G connectivity, you could pay as much as $829, but even that was significantly less than what many people expected.

The price was important to driving early sales. The iPad was by no means inexpensive, but the price point Apple chose put the device within reach of the curious who were already familiar with the iPhone and the exploding app economy.

It’s hard to argue with the approach. Early sales of the iPad were brisk, with over three million sold in the first 80 days and 15 million by the time the iPad 2 was launched.

Brand new product categories don’t normally take off like that, but the iPad was different. By leveraging the App Store and familiarity with iOS from the iPhone, Apple had a built-in audience that knew how to use an iPad before they had ever seen one.

However, looking back, the same factors that led to that initial success were the very things that ultimately held the iPad back. That first keynote cemented the iPad as a consumption device in the minds of users and the press. There were people like Federico who found ways to use the iPad as a desktop replacement, but stories like his were largely an exception to the rule, until the introduction of the iPad Pro in 2015.

iPad keynotes are very different today. The black leather chair is gone, and demos emphasize creative apps like Adobe Photoshop. The ‘single slab of multitouch glass’ is gone too. Sure, the iPad can still be used on its own and can transform into whichever app you’re using as it has always done, but there are many more layers to the interaction now with Split View, Slide Over, and multiwindowing, along with accessories like the Smart Keyboard Folio and Apple Pencil.

That’s quite a transformation for a product that has only been around for 10 years, and with the more recent introduction of the iPad Pro and iPadOS, in many ways it feels as though the iPad is just getting started. Aside from the Apple Watch, there’s no other product in Apple’s lineup that seems poised for greater change and carries more promise than the iPad. It may have started as a big iPhone, but the iPad has finally begun to establish an identity of its own that still delivers on Steve Jobs’ original promise of a new category of device that balances the intimacy of the iPhone and the capabilities of a Mac.

- I’ve tried my best to track down the original source for each mockup and note them in the captions of the gallery, although with the amount of liberal reposting of images that was happening ten years ago, some undoubtedly originated elsewhere. ↩︎

- The same leather chair would make another appearance for the iPad 2 launch. ↩︎

- Who knows whether it was intentional, but there was a humorous moment as Jobs scrolled down The New York Times’ homepage past a block of Adobe Flash content that didn’t load because it wasn’t supported by the OS. Jobs’ famous essay, Thoughts on Flash, was published just three months later. ↩︎

- Without hardware to test their apps on, companies like The Omni Group, which had decided to go all-in on the iPad, resorted to mocking up apps on faux iPads they constructed with a 3D printer, while Marco Arment turned to cardboard mockups. ↩︎

- With the wild success of games on the iPhone and the big, bright display of the iPad, the potential for the iPad to become a gaming device was clearly on the minds of Apple executives, as evidenced by the somewhat unusual invitation to the keynote that was extended to gaming site Kotaku. ↩︎

- Including The New York Times app in the presentation was a curious choice given that it also played a prominent role in the demonstration of web browsing at the beginning of the keynote. The New York Times’ app made for a nice demo too, but muddied the web browsing story that was so clearly an important component of the presentation. ↩︎

- Remarkably, compatibility mode is still with us a decade later. ↩︎