The trouble with looking back over a long period is that time has a way of compressing history. The clarity of hindsight makes it easy to look back at almost anything and be disappointed in some way with how it turned out years later.

We certainly saw that with the anniversary of the introduction of the iPad. Considered in isolation a decade later, it’s easy to find shortcomings with the iPad. However, the endpoints of the iPad’s timeline don’t tell the full story.

It’s not that the device is short on ways it could be improved; of course, it isn’t. However, the path of the iPad over the past decade isn’t a straight line from point A to point B. The iPad’s course has been influenced by countless decisions along the way bearing consequences that were good, bad, and sometimes unintended.

The 10th anniversary of the iPad isn’t a destination, it’s just an arbitrary point from which to take stock of where things have been and consider where they are going. To do that, it’s instructive to look at more than the endpoints of the iPad’s history and consider what has happened in between. Viewed from that perspective, the state of the iPad ten years later, while at times frustrating, also holds reason for optimism. No single product in Apple’s lineup has more room to grow or potential to change the computing landscape than the iPad does today.

Just a Big iPhone

No product is launched into a vacuum, and the origin of the iPad is no different. It’s influenced by what came before it. In the ten years since April 3, 2010, that context has profoundly affected the iPad’s adoption and trajectory.

In hindsight, it seems obvious that the iPad would follow in the footsteps of the iPhone’s design, but that was far from clear in 2010. Take a look at the gallery of mockups leading up to the iPad’s introduction that I collected for a story in January. The designs were all over the place. More than two years after the iPhone’s launch, some people still expected the iPad to be a Mac tablet based on OS X.

However, after spending over two years acclimating consumers to a touch-based UI and app-centric approach to computing, building on the iPhone’s success was only natural. Of course, that led to criticisms that the iPad was ‘just a big iPhone/iPod touch’ from some commentators, but that missed one of the most interesting and overlooked part of the iPad’s introduction. Sure, Apple leaned into the similarities between the iPhone and the iPad, but even that initial introduction hinted at uses for the iPad that went far beyond what the iPhone could do.

Apple walked a careful line during that introductory keynote in January 2010. Steve Jobs’ presentation and most of the demos were a careful mix of showing off familiar interactions while simultaneously explaining how the iPad was better for certain activities than the iPhone or the Mac. That went hand-in-hand with UI changes on the iPad that let apps spread out, flattening view hierarchies. The company didn’t stop there, though.

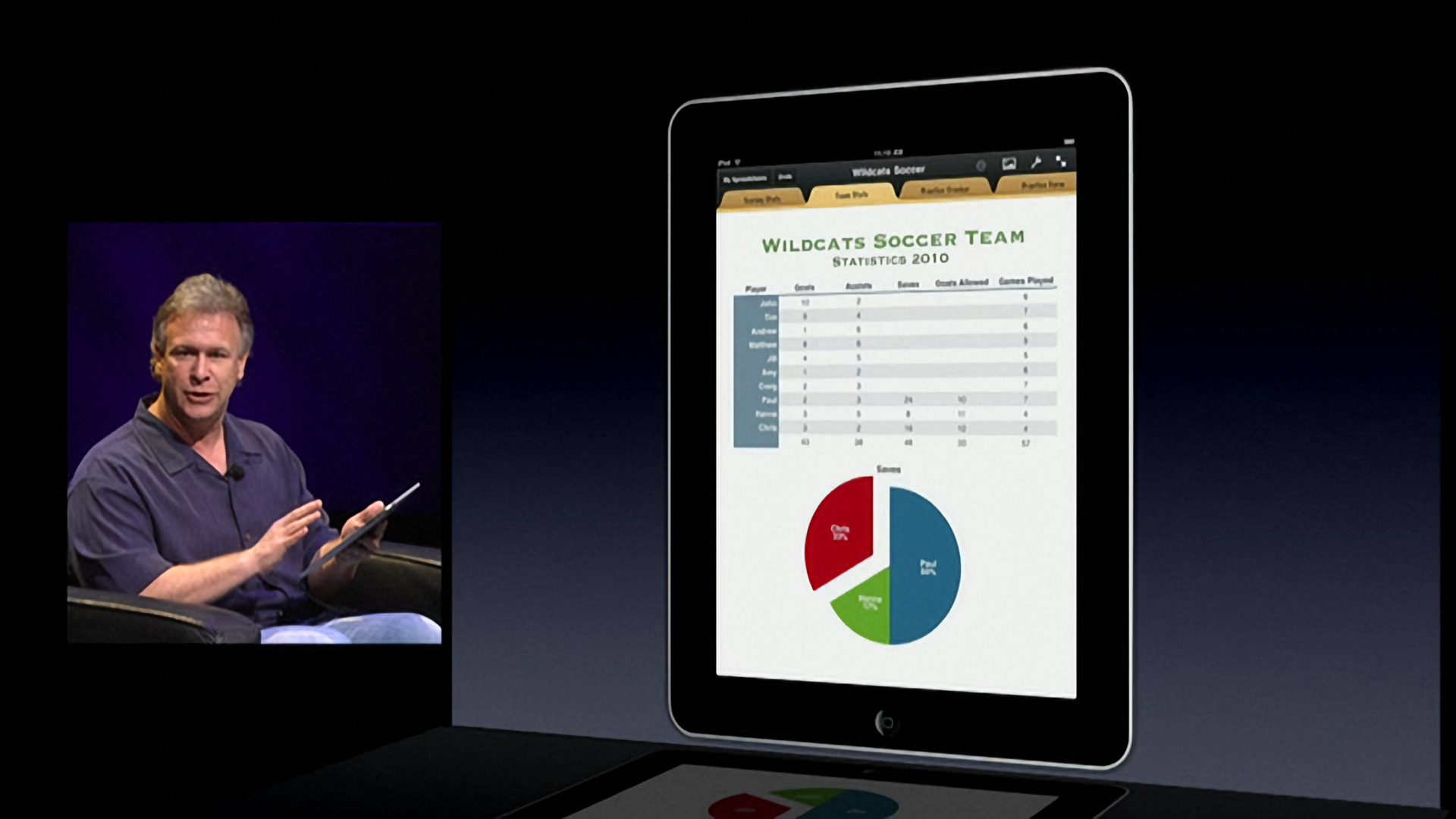

Apple also provided a glimpse of the future. Toward the end of the iPad’s debut keynote, Phil Schiller came out for a demo of iWork. It was a final unexpected twist. Up to this point, the demos had focused primarily on consumption use cases, including web and photo browsing, reading in iBooks, and watching videos.

The iWork demo was a stark departure from the rest of the presentation. Schiller took the audience on a tour of Pages, Numbers, and Keynote. They weren’t feature-for-feature copies of their Mac counterparts. Instead, each app included novel, touch-first adaptations that included innovative design elements like a custom software keyboard for entering formulas in Numbers. Apple also introduced a somewhat odd combination keyboard and docking station accessory for typing on the iPad in portrait mode.

What stands out most about this last segment of the iPad keynote isn’t that the iPad could be used as a productivity tool, but the contrast between how little time was spent on it compared to how advanced the iWork suite was from day one. As I explained in January, I suspect that to a degree, Apple was hedging its bets. Perhaps, like the original Apple Watch, the company knew it had built something special, but it wasn’t sure which of the device’s uses would stick with consumers.

The iPhone was still a young product in 2010. It was a hit, but consumers were still new to its interaction model. The App Store was relatively new, too, and filled with apps, many of which would be considered simple by today’s standards.

By tying the iPad closely to the iPhone, Apple provided users with a clear path to learning how to use its new tablet. Spotlighting familiar uses from the iPhone and demonstrating how they were better on the iPad tapped into a built-in market for the company’s new device. But the more I look at that first iPad keynote in the context of the past decade, the more I’m convinced that there was something else happening during that last segment.

Apple knew it was on to something special that went beyond finding better ways to do the same things you could already do on an iPhone. If that was the extent of the iPad’s potential, the company wouldn’t have invested the considerable time it must have taken to adapt the iWork suite to the iPad, and later update the Mac versions to align better with their iOS counterparts. iWork was a harbinger of the more complex, fully-featured pro apps on the iPad that have only recently begun to find a foothold on the platform.

However, there’s no doubt that it was the emphasis on consumption apps that set the stage for the iPad’s early years.

The First Five Years

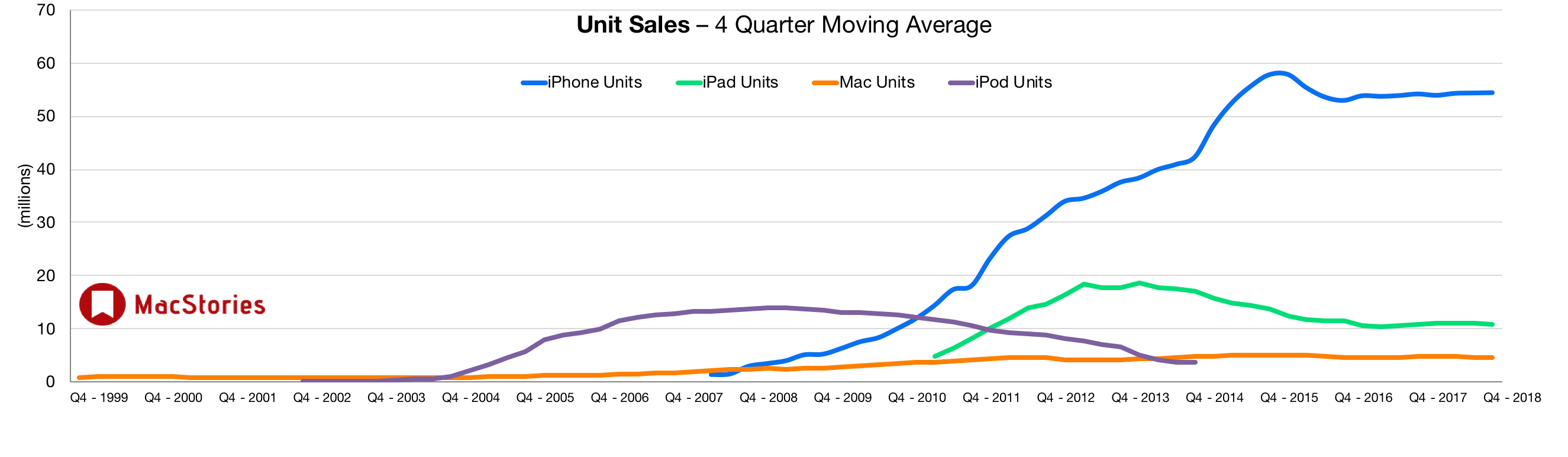

Initial sales of the iPad were strong. The first day it was available, Apple sold 300,000 iPads. After four weeks, that number climbed to one million. Adoption was faster than the iPhone. In fact, it was faster than any non-phone consumer electronic product in history, surpassing the DVD player.

The sales results were a vindication of the iPad’s launch formula. So when it was time to roll out the iPad 2, Apple sought to capture lightning in a bottle again by using the same playbook, right down to the black leather chair used for onstage demos in the first keynote.

The structure of the iPad 2 presentation was the same too, closing with a demo of new, sophisticated apps from Apple that was reminiscent of Schiller’s iWork demo. This time, the company showed off iMovie and GarageBand. iWork had been impressive the year before, but something about the creative possibilities of making movies and music on a device you held in your hands recaptured the excitement and promise the iLife suite had ignited on the Mac years before. In 2010, Apple showed that you could get work done on an iPad, but in 2011, the company showed customers they could make art.

In the wake of the iPad 2 keynote, the iPad seemed poised to jump-start a computing revolution, but instead, Apple’s iPad efforts appeared to stall. Steve Jobs’ passing in late 2011 may have been a contributing factor, but paradoxically, it was Apple’s successful strategy of tying the iPad so closely to the iPhone that also held it back.

iPad sales continued to climb in 2011 and 2012. Apple responded by rapidly iterating on the device and expanding the lineup. In 2012 alone, Apple released the third and fourth generation iPads, plus the iPad mini. By the time the ultra-thin iPad Air debuted in late 2013, though, things had begun to take a turn for the worse.

After those first two keynotes, Apple’s push into productivity and creativity apps on the iPad slowed. At the same time, iPads were built to last. Users didn’t feel the same sense of urgency to replace them every couple years as they did with iPhones. Coupled with the fact that few apps were pushing the hardware, sales began to decline.

The picture wasn’t completely bleak, though. Third parties took up the cause and pushed the capabilities of the platform with apps like Procreate, Affinity Photo, Editorial, and MindNode, and for some uses, the iPad was a worthy substitute for a Mac. However, with the iPad still moving in lockstep with the iPhone, developers and users began to run up against limitations that made advancing the iPad as a productivity and creativity platform difficult.

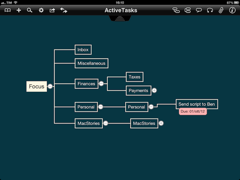

iThoughts, iOS 6.

iBooks, iOS 6.

Paper, iOS 6.

Evernote, iOS 6.

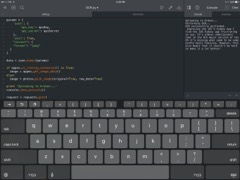

Pythonista, iOS 6.

Pinbook, iOS 6.

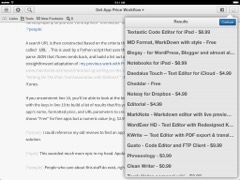

Editorial, iOS 7.

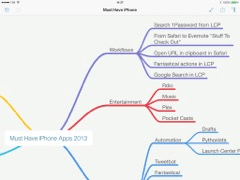

MindNode, iOS 7.

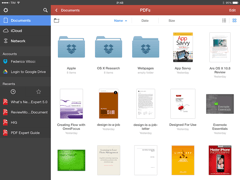

PDF Expert, iOS 7.

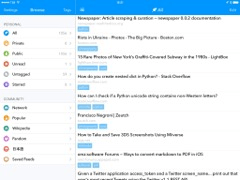

Pushpin, iOS 7.

Terminology, iOS 7.

Instapaper, iOS 7.

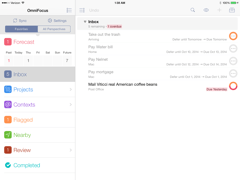

OmniFocus, iOS 7.

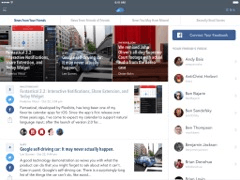

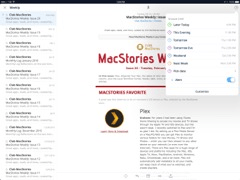

Nuzzel, iOS 8

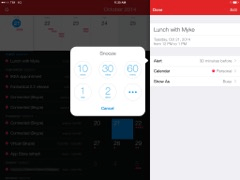

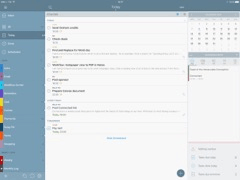

Fantastical, iOS 8.

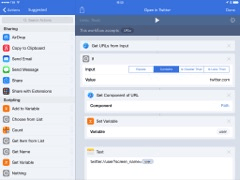

Workflow, iOS 8.

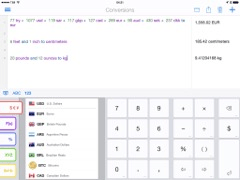

Soulver, iOS 8.

Editorial, iOS 8.

Todoist, iOS 8.

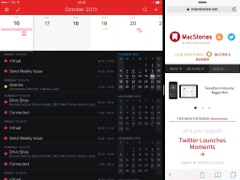

Fantastical, iOS 9.

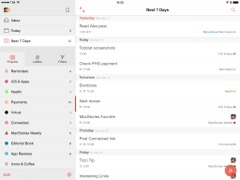

2Do, iOS 9.

Pigment, iOS 9.

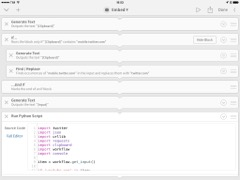

Pythonista, iOS 9.

Spark, iOS 9.

PDF Expert, iOS 9.

Chief among the stumbling blocks were the lack of file system access and multitasking. The app-centric nature of iOS worked well for the iPhone, but as apps and user workflows became more sophisticated, the inflexibility of tying files to particular apps held the iPad back. The apps-first model was simple, but processing a file in multiple apps meant leaving a trail of partially completed copies in the wake of a project, wasting space, and risking confusion about which file was the latest version.

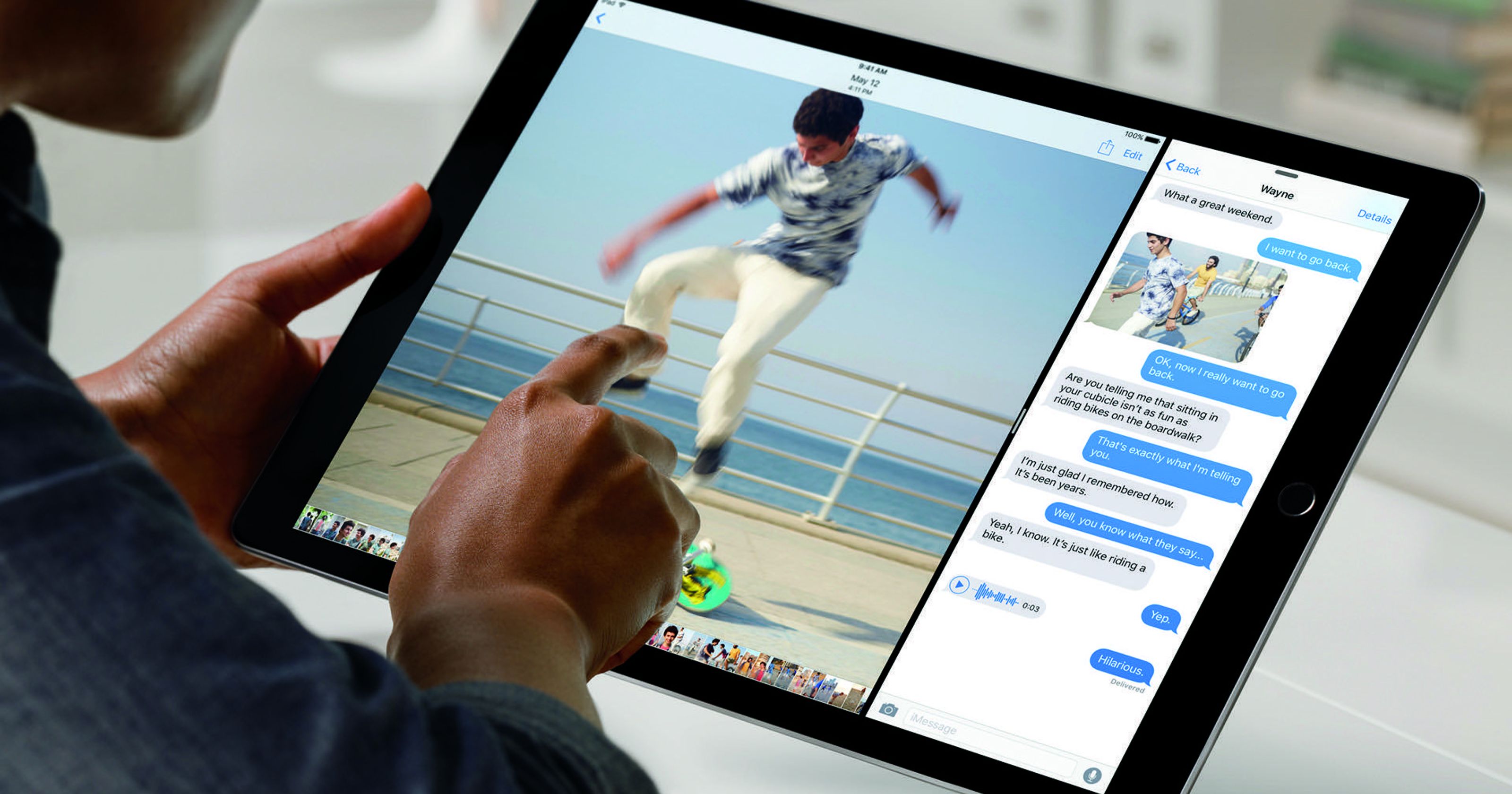

The lack of multitasking became a speed bump in the iPad’s path too. The larger screen of the device made multitasking a natural fit. However, even though the hardware practically begged to run multiple apps onscreen, the OS wasn’t built for it, and when it finally was, the first iterations were limited in functionality.

We don’t know what the internal dynamic was at Apple during this time, but the result was that, despite early optimism fueled by the iWork apps, GarageBand, and iMovie, the iPad failed to evolve into a widely-used device for more sophisticated productivity and creative work. It was still a capable device, and increasing numbers of users were turning to it as their primary computer. However, that only added to the building frustration of users who sensed the platform’s progress leveling off just as they were pushing it harder.

Pro Hardware

As the first five years of the iPad concluded, sales continued to decline. However, 2015 marked the first signs of a new direction for the iPad with the introduction of the first-generation iPad Pro, a product that began to push the iPad into new territory.

The original iPad Pro was a significant departure from prior iPads. Not only was it Apple’s most powerful iPad, but it introduced the Apple Pencil and Smart Keyboard cover.

The Pencil added a level of precision and control that wasn’t possible using your finger or a third-party stylus to draw or take notes. With tilt and pressure sensitivity and low latency, the Pencil opened up significantly more sophisticated productivity and creative uses. The Smart Keyboard did the same for productivity apps, turning the iPad into a typing-focused workstation.

The hardware capabilities of the iPad Pro have continued to advance steadily, outpacing desktop PCs in many cases. However, sophisticated hardware alone wasn’t enough to propel the iPad forward. It was certainly a necessary first stop, but Apple still had to convince developers to build more complex pro apps that made use of the iPad’s capabilities.

Pro Apps and Business Models

As the first decade of the iPad comes to a close, Apple continues to grapple with fostering a healthy ecosystem of pro-level apps. For most of the past decade, the iPad app ecosystem has been treated the same as the iPhone’s. The company, however, seems to have recognized the differences and has made adjustments that have substantially improved the situation.

As of the last time Apple reported unit sales, iPad sales were roughly double those of the Mac, but far smaller than the iPhone.

The challenge of the iPad market is that it’s much smaller than the iPhone market. At the same time, pro-level apps are inherently more complex, requiring a substantially greater investment than many iPhone apps. That makes embarking on these kinds of iPad-focused pro app projects far riskier for developers.

However, Apple’s recent moves have significantly improved the situation. The first step was to implement subscriptions. Although they aren’t limited to the iPad, subscription business models have provided developers with the recurring revenue necessary to maintain sophisticated apps long term. Subscriptions haven’t been popular with some consumers, especially when a traditionally paid up front app transitions to a subscription. Still, the developers I’ve spoken with who have made it through the transition are doing better than before.

The second and less obvious move Apple made was the introduction of Mac Catalyst apps, which allow iPad developers to bring their apps to macOS. To be sure, Mac Catalyst is designed to breathe new life into the stagnant Mac App Store, but it also benefits the iPad. As I wrote last summer, Mac Catalyst aligns the iPad more closely with the Mac than ever before. By facilitating simultaneous development for both platforms, Mac Catalyst significantly increases the potential market of users for those apps and encourages the use of the latest iPadOS technologies, both of which promise to advance the platform.

A good example of this in action is Twitter’s Mac and iPad apps. Twitter’s iPad app languished for years; however, last fall Twitter launched a Mac Catalyst version of its app. Although the app had some rough edges, it included features you’d expect on the Mac like extensive keyboard shortcuts. Less than three weeks later, the iPad app was updated with extensive keyboard support too.

The third software piece of the puzzle Apple has addressed is iPadOS. Going into WWDC 2019, significant iPad-specific updates to iOS were anticipated, but no one saw a separate OS coming. Currently, the overlap between iPadOS and iOS is extensive, but the introduction of iPadOS sent a message to developers that Apple was ready to start differentiating the feature sets of its mobile OSes to suit the unique characteristics of each platform. Over time, I expect we’ll see even more differences between the platforms emerge, such as the cursor support added to iPadOS with iPadOS 13.4.

It’s still too early to judge whether the software-side changes to the iPad will succeed in encouraging widespread adoption of the latest hardware capabilities. However, early signs are encouraging, such as Adobe’s commitment to the platform with Photoshop and the announced addition of Illustrator. My hope is that with time, Apple’s substantial investment in both hardware and software will create a healthy cycle of hardware enabling more sophisticated apps and apps pushing hardware advancements.

The trajectory of the iPad is one of the most interesting stories of modern Apple. Taking off as strongly as the device did in the aftermath of the iPhone made it look, for a time, like Apple had repeated the unbounded success of the iPhone.

Although the company managed to jump-start sales of the iPad by tying it to the iPhone, it became clear after a couple of years that the iPad wasn’t another iPhone. That doesn’t make the iPad a failure. It’s still the dominant tablet on the market, but it hasn’t transformed society and culture to the same degree as the iPhone.

With the introduction of advanced hardware, new accessories, iPadOS, Mac Catalyst, and new business models, the iPad has begun striking out on its own, emerging from the shadow of the iPhone. That’s been a long time coming. Hitching the iPad to the iPhone’s star was an undeniably successful strategy, but Apple played out that thread too long.

Fortunately, the company has begun to correct the iPad’s course, and I couldn’t be more excited. The hardware is fast and reliable, and soon, we’ll have an all-new, more robust keyboard that can double as a way to charge the device. Perhaps most intriguing, though, is the introduction of trackpad and mouse support in iPadOS 13.4. Although it was rumored, most people didn’t expect to see trackpad support until iPadOS 14. I’m hoping that means there is lots more to show off in the next major release of iPadOS.

Ten years in, the iPad is still a relatively young device with plenty of room to improve. Especially when you consider that the iPad Pro with its Apple Pencil and Smart Keyboard is only five years old, there is lots of room for optimism for the future. The iPad may have been pitched as a big iPhone at first, but its future as a modular computing platform that is neither a mobile phone nor traditional computer is bright.

You can also follow all of our iPad at 10 coverage through our iPad at 10 hub, or subscribe to the dedicated iPad at 10 RSS feed.