I finally had time to sit down and write on my iPad after 72 hours spent traveling between continents, meeting friends I’ve long known only through Twitter and their blogs, visiting San Francisco, and trying American pasta. And also going to my first Apple event.

After nearly six years spent publishing MacStories and covering Apple media events from the comfort of my bedroom through live streams and Twitter, getting the opportunity to enjoy an event in person surrounded by people whom I’ve remotely known for a long time is truly something special. I needed time to process the information and discussions from the keynote, and I’m still catching up on the announcements from an outside perspective. As usual, Apple has only shared a portion of their announcements on stage, saving the details and fine print for its website, various FAQ sections, and a new version of iOS.

Thankfully, the MacStories team has done an excellent job in covering the news from Apple’s March 9th event and providing in-depth overviews. I’ll focus on my personal thoughts and considerations after attending the event and trying Apple’s new MacBook and upcoming Apple Watch.

A Note on the Event

This was my first Apple event and my first time in the United States. I flew to London on Sunday morning and got on a connecting flight to San Francisco, where I arrived at 8 PM on Sunday. I stayed in San Francisco for the morning of the event, grabbed lunch with some friends, recorded a podcast with Jason Snell, then went back to the airport and left at 9 PM on Monday. At 10 PM on Tuesday, I was back in Rome. The plan was crazy and the schedule was tight, but I’m glad I went through with it – the experience, even if short, was incredible.

After grabbing coffee at Blue Bottle with Matthew Panzarino, we headed to the Yerba Buena Center, which at 8 AM was already packed. Having covered Apple events over the Internet for years, my first reaction was that I had been catapulted into a bizarre Real Life Twitter where profile pictures moved and talked and interacted with each other. I met people I’ve considered online friends for years such as Rene, Serenity, Jim, Jason, Dan, and so many others. This probably sounds obvious and trite, but seeing someone in person after years of online interactions is completely different, in a fantastic way.

Being my first Apple event, I chose to relax and enjoy it rather than obsessing over liveblogging and taking pictures. It was my first time, and I figured I didn’t want to miss a single moment. The best part of being at the event is that you see and meet executives mingling with the guests – but I’ll let the selfies with Tim Cook (yes!) and Eddy Cue (yes!) give you an idea of how special it can be (for the ones looking to have more color, they are all extremely warm and kind).

I was able to go with other press attendees in the demo room (more like a dedicated structure Apple built specifically for the event) to see the Apple Watch and new MacBook up close. I’ll save the details for later, but, again, after years of watching hands-on videos on YouTube and reading first impressions online, experiencing it in person felt odd and great at the same time.

After the event, I went to have lunch with Jason, Rene, and Serenity. I had pasta and Oasis started playing on the radio, which seemed like a fitting conclusion to a wonderful morning.

ResearchKit

(Read the MacStories overview)

As someone who relies on Apple’s Health app every day and had to go through medical research years ago for a brief period of time, I find ResearchKit to be Apple’s most profound and impactful announcement from Monday.

I remember that, as a patient, medical research wasn’t fun. In my case, I was going through treatments and trying experimental drugs three years ago, and I was handed paperwork that I needed to sign and fill with information about chemo effects and how I was feeling. Having to fill forms manually while you’re sick – even if it’s for a greater cause – isn’t the most pleasant experience. I did it, but it felt antiquated and strangely old-fashioned when compared to modern advancements in cancer treatment. Not to mention the bureaucracy and, as Apple’s Jeff Williams outlined, the infrequency and inconsistency of data and the limited amount of people willing to share their information.

Using an iPhone as a sensor-laden device for medical research seems genius to me and exactly what has to be done to expand medical research and make it more connected and accessible. When dealing with patients – and, obviously, my experience is limited to what I went through, so circumstances may be different – or people who are simply interested in helping with medical research, it’s important to make the data collecting process seamless and reliable. An iPhone is always with you (possibly on you) and it’s filled with sensors that can accurately measure parameters such as steps and vocal intensity; it’s got a screen that can assess manual interactions through touch; with Bluetooth and wireless connections, it can connect to certified medical devices and store data securely in a central repository that can be shared with other apps.

When I was watching the presentation, I could feel that ResearchKit was a big deal to the people who worked on it. But, at the same time, I imagined some of the reactions on Twitter and the comments from people who were thinking the announcement was boring. After introducing a framework that is deeply changing personal health tracking (and that will power Apple Watch), I believe that going one step further to embrace medical research through iOS features and apps is an important new direction for Apple’s Health initiative.

I was talking to Six Colors’ Jason Snell about ResearchKit earlier this week, and I still have questions and doubts. This is a long-term project, and, aside from launch partners, it’s unclear how (and if) ResearchKit will be adopted internationally and on what scale. Will local institutions from small towns like Viterbo and Terni in Italy eventually participate in ResearchKit-powered apps? How will the open-source nature of the project affect the availability of ResearchKit apps and services on other platforms? Will interest in ResearchKit fade over time, or will it really take off and become a de-facto industry standard?

Unlike iOS’ Health app, real results from ResearchKit will only be felt in years, not months. This is suggested by Apple’s own presentation, too.

I genuinely believe that Apple and its launch partners care about starting ResearchKit now because an iPhone can be immensely more versatile and engaging than forms and signup letters when it comes to collecting medical data from people. Like Health, ResearchKit has the potential to bring meaningful change for millions of people.

After six hours we have 7406 people enrolled in our Parkinson’s study. Largest one ever before was 1700 people. #ResearchKit

— John Wilbanks (@wilbanks) March 10, 2015

The New MacBook

(Read the MacStories overview)

I’m not exactly qualified to talk about MacBooks as an iPad is my primary computer, but I still use my MacBook Air twice a week to record podcasts, and there are some truly interesting choices in Apple’s latest laptop.

As I discussed on Connected after rumors of a new 12-inch MacBook first surfaced, the absence of dedicated ports for external connections may be unpopular but it’s not surprising. The future is wireless and a vast portion of laptop users don’t ever need to plug in thumb drives, external backup drives, printers, or monitors. It’s important to stress that, when looking at the next few years of changes in the computer industry, Apple can’t prioritize the needs of a niche of tech-savvy users, for they experience more angles of technology than other people.

The new MacBook may not be a Mac for everyone right now. There are people who need a MacBook with multiple ports, and that is fine, because there are options. But what Apple is doing, I think, isn’t shortsighted – quite the opposite. At some point, you need to draw a line and understand which technologies to bet on for the next decade. There’s always a chance that Apple may be wrong in thinking external peripherals won’t be in the future of the average MacBook customer, but, historically, their process has been accurate.

The trackpad in the new MacBook is one the freakiest technologies I’ve tried in a while. As Matthew Panzarino writes, it doesn’t move. But, when I tried it, my brain was instantly tricked into believing that, by pressing down, my finger was going deep into the trackpad, which was clicking and moving according to different levels of pressure. That’s how the Force Touch illusion works.

Apple has built a deceptively clever system based on the Taptic Engine, previously seen on the Apple Watch. With Force Touch, the new MacBook and updated MacBook Pro effectively receive a new OS X gesture, which enables an interesting new array of functionalities and shortcuts. In my demo, I was shown activating different menus in iMovie, adjusting the skip back/forward speed in QuickTime with pressure, and triggering smart data detectors with a deep click.

At this point, I believe Force Touch could make even more sense on iOS, where it’d be reinforced by the metaphor of directly manipulating content with multitouch. But I’ll save this argument for some iOS 9 wishes.

Apple Watch

(Read the MacStories overview)

I had the opportunity to try an Apple Watch after the presentation, and I found it to be much smaller than I was expecting, with a pleasant compact shape that felt just right on my wrist. Following the initial surprise, some of my suspicions were confirmed: I’m going for the 42mm model, I’ll get a Stainless Steel watch, and, as I argued many times in the past, I think Apple Watch is uniquely positioned to enhance personal fitness and health tracking.

Apple focused on three key built-in features of the Watch (timekeeping, communication, and fitness) and then cleverly went into a demo for a typical day in the life of an Apple Watch user, including third-party apps. I feel like Apple painted a concise, clear picture of the Watch that many aren’t seeing in their obsession to find a one-size-fits-all “use” of the device.

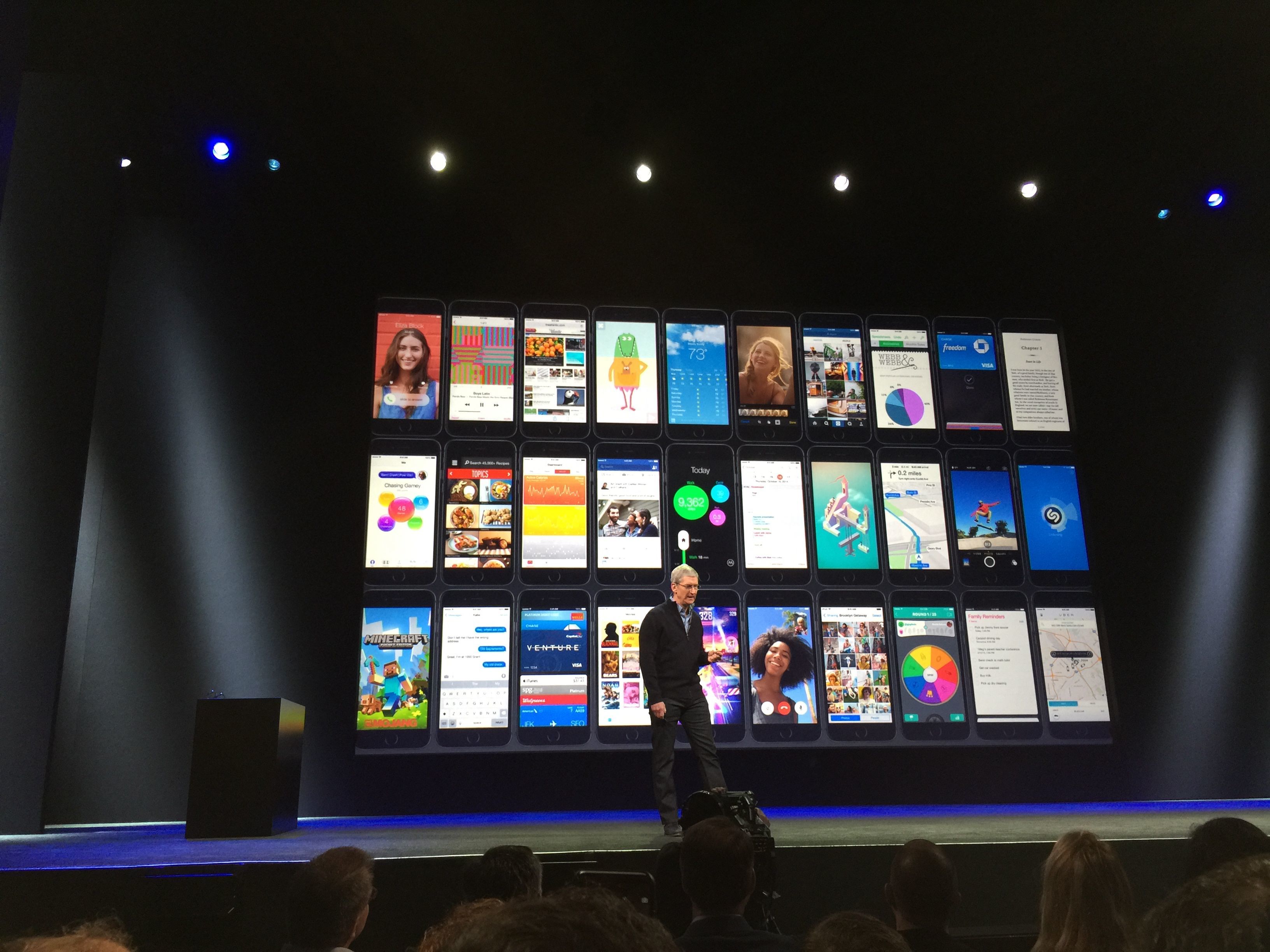

Apple has learned from the iPhone playbook after nearly seven years of App Store: what started as an iPod, a phone, and an Internet communicator is now an entire industry that spans entertainment, health, productivity, and dozens of other categories with over a million apps. The original iPhone launched with tentpole features focused on communication and the web, but it evolved into a mosaic of services and use cases that nobody could have imagined years ago. I believe the same will happen with Apple Watch, and sooner than we’re expecting because of the advantage granted by seven years of App Store.

There’s no single use for the Apple Watch because there’s no single use for an iPhone, either. At a basic level, an iPhone is a phone and it connects to the Internet; similarly, a Watch shows time and is connected to an iPhone. But it was software that helped turn the iPhone into a revolutionary mobile computer, and it seems clear to me that Apple hopes the same will happen with the Watch. With a substantial difference: the Apple Watch will be worn.

We shouldn’t be arguing about a commonly accepted use of the Apple Watch. Everybody uses a computer differently, after all. Rather, a broader question remains: is the path for more useful, intelligent technology leading to wearable devices?

I’ve long argued on MacStories and Connected about the potential of devices that are on you and have access to a different subset of data and context about you and your habits. Unlike smartphones and tablets, wearables can take advantage of discrete interactions and information that wouldn’t be as easily tracked otherwise. This mesh of constant context and smaller chunks of interactions will redefine how we interact with our devices going forward.

From September 2014:

For one, Apple understands the importance of a device that’s in constant contact with your skin and built in sensors and a haptic feedback system to take advantage of that unique placement. And the extent of Apple’s interplay of custom hardware and software will, of course, only be clear years after Apple Watch 1.0.

With the first version of the Watch, Apple is starting with a few sensors to track activity and movement during the day, plus heart rate. In the demo I was given, sensing the user’s heart rate took just a couple of seconds and it seemed more accurate than apps like Health Mate and Instant Heart Rate, which use the iPhone’s camera and flash to calculate heart rate. Similarly, Apple’s solution for reminding users to stand up and move more appeared to be clever and elegant, with an intuitive circle-based UI and gentle reminders that tap you on the wrist.

From a fitness perspective, this is a powerful idea. A device that is always on me – on my skin – knows better than my iPhone when it’s time to move and how I’m feeling when doing so. I have been using my iPhone as a health and fitness assistant, but, by its own nature, the iPhone doesn’t have direct access to my body. This is why I’m excited to see how Apple Watch will work with exercise machines during workouts (which Apple announced on Monday) and apps like Run 5k, which will use sensors on the watch alongside an iPhone app to understand user fatigue when running and walking.

For me, the key to understanding Apple Watch is a willingness to accept that software, sensors, and the wearable form factor open a field of possibilities we still can’t fully grasp. Apple is describing what they consider the primary functionalities of the Watch, but I get the feeling that nobody knows what is going to happen, exactly. And that’s the point – instead of being a criticism to Apple for a lack of focus, this uncertainty should be regarded as excitement for a platform that’s already open to innovation.

Just as importantly, Apple is relying on traditional watchmaking traits such as finely crafted materials, lust, and a keen sense of fashion to get people to want and wear this device. This is a new field for the company: unlike tech (where purchase decisions are primarily driven by utility), most fashionable goods (and particularly luxury ones) appear to be bought almost irrationally. However, wanting to look nice, self expression, and desire aren’t irrational or inexplicable phenomena – they are simply different from the criteria used to evaluate consumer electronics products. This is why Apple Watch is such an interesting new venture – it’s a modern take on the traditional watch combined with a vision for the future of mobile software.

Technology is inevitably getting more personal because we want computers to help us in our daily lives, and our body is the next logical frontier. We’re seeing this in the software that’s being announced for Apple Watch. The aforementioned Run 5k will combine sensors and haptic feedback to know when you should slow down. Shazam will let you recognize songs and sing along without scrambling to find your phone. You’ll be able to scan boarding passes from your wrist (no more holding an iPhone and passport at the same time). Todoist will remind you to complete tasks with a gentle tap. All of this was, to an extent, already possible with an iPhone, but it’ll be faster, more convenient, timely, and personal with an Apple Watch. We’re on the cusp of seeing mobile interactions being redefined by the convenience of a wearable, and Apple’s edge will be the rich catalogue of the App Store.

That could also be the device’s initial problem, though. Because Apple Watch will be launched as a satellite device to the main iPhone experience, apps will be limited in capabilities and native apps (presumably more flexible and featured) won’t ship for a few months. It’ll be tricky to balance initial results from WatchKit apps with the promise of more powerful software coming down the road, but I’m confident that the first wave of Watch apps will prove to be useful and cool just enough to justify the utility aspect of the Watch (sheer fashion appeal possibly being, again, an even stronger factor at launch and over time).

After trying an Apple Watch, I’m also more convinced that successful Watch apps will be the ones that won’t try to cram entire iPhone experiences on the wrist. On the iPhone, the apps that have reinvented our approach to mobile technology are those that didn’t emulate PC software for the sake of feature parity. Similarly, Apple Watch developers should consider crafting apps that make sense for limited interactions and that use a different context to be useful. Based on the demo I had, Apple’s own communication features seemed like a great example of this. Rather than bringing the full iMessage experience to the Watch, Apple rebuilt its communication layer to be more intimate and personal with sketches, heartbeats, taps, and animated emoji.

Once I got into the mindset that all software will be reinvented in the transition to our wrist, I felt more comfortable about the big picture of Apple Watch. I’ll need more time to evaluate bands (the Milanese was smooth and beautiful), collections (the Sport’s satin finish is surprisingly cool-looking), and software navigation (the entire OS structure is different from iOS). But I’ve been thinking about the high-level perspective of Apple Watch (and wearables in general) for months, and these past few weeks have cemented my belief that, when it comes to software, the quest for a single use leads nowhere.

We want technology to help us every day. There’s no single way to achieve that.