Back in 2006, when Apple was still rumored to be working on a revolutionary mobile phone, many wondered if such device would be able to do core tasks like email and messaging as well as RIM’s BlackBerry. Months later, when the iPhone was officially announced at Macworld, the introduction of the device alone led some people to write that it was “already impacting its new competitors” – namely RIM, and its BlackBerry line of phones that had captured a great portion of corporate America. Yet, those people were right: the numbers are speaking for themselves now, and the many issues behind RIM’s poor management and marketing choices can be traced back to the iPhone’s introduction.

At Macworld 2007, a healthy-looking Steve Jobs said: “This is a day I’ve been looking forward to for two and half years. Every once in a while, a revolutionary product comes along that changes everything. […] Today we’re introducing three revolutionary products of this class.

Today Apple is going to reinvent the phone”.

Looking back at that day now, it’s a shared sentiment among those who have been following Apple for the past years that Steve touched his highest point in presentation style and product-unveiling skills with that keynote. Because while Steve may no longer be with us today, his words still resonate stronger than ever. On that day, Apple did reinvent the phone. And as it turns out, the revolution wasn’t just about multitouch and elegant hardware design.

It was about the software.

Later on during that keynote, Steve arrived at the third section of the presentation and iPhone feature set, which was also described as an “Internet communications device”. The first item in that slide was Rich HTML email – “for the first time, really rich email on a mobile device”, he said. Sure enough, the iPhone’s Mail app was demoed on stage to show off its rich HTML-parsing capabilities, which included inline images, rich text, support for phone numbers and web links, and more. When the iPhone went on sale six months later, on June 29, and debuted online to rave reviews from the press, many praised its email capabilities, among other things.

But then something happened in the following months. As Apple kept adding features to iPhone and refining its core apps including Mail, users and developers began wondering when Apple would allow for third-party apps to be installed on the device. For as much as Apple was adding new functionalities and fixes, there are always niches and sub-markets that Apple can’t address in new software releases – corporate email was one of them, as, admittedly, that were still several things Apple wasn’t adding to its email client to please business users from corporate environments. When Apple did confirm its plans to open up iPhone OS and offer an App Store, users wondered if it would be possible, like it still is on a Mac, to install replacements for the “core apps”, such as the browser, email client, or calendar application. In a somewhat unexpected and much criticized turn of events, Apple made it clear to developers that it would not accept third-party apps duplicating the functionality of build-in iPhone applications.

John Gruber has a good recollection of the events from 2008 – case in point MailWrangler, an email app that was rejected at the time.

I have a theory. It is more, well, emotional than logical. But it’s the only theory I can think of that makes any sense at all and fits the available evidence. The theory is that there is an unpublished rule that Apple — and in this case, where by “Apple” I really mean “Steven P. Jobs” — will not publish third-party apps that compete with or replace any of the four apps in the iPhone’s default “dock”: Phone, Mail, Safari, and iPod.

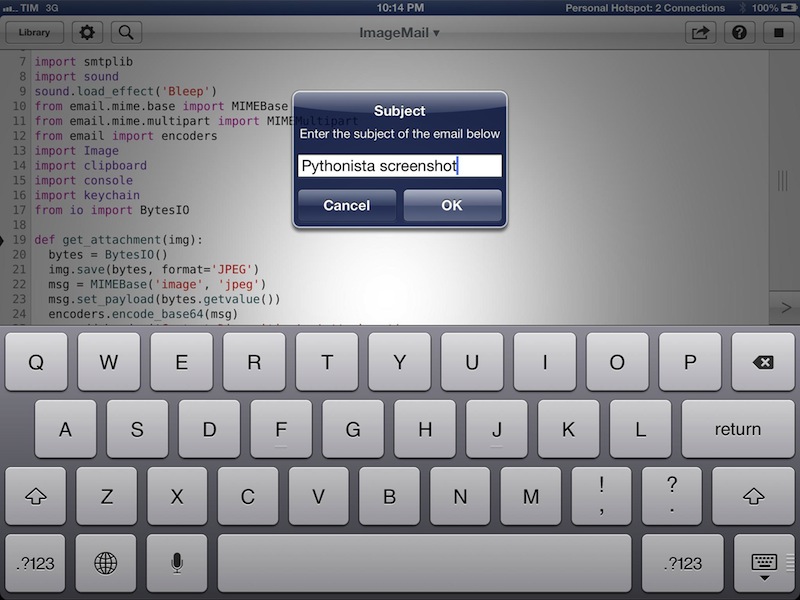

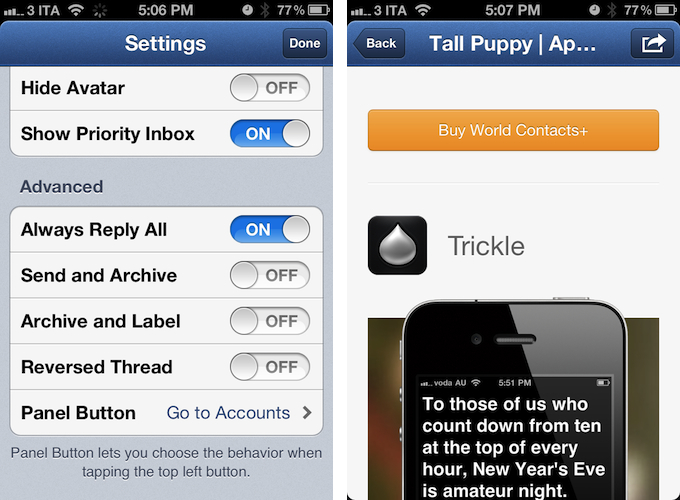

In the following years, in spite of App Store-related controversies showing up every once in a while, developers more or less “understood” how Apple’s approval process worked, and kept working on apps that would be “safe” for sale within Apple’s rules. Publishing a set of guidelines certainly helped in making things clear for everyone, but new apps that belonged to categories not mentioned in the guidelines would still appear in the App Store, forcing Apple to revise its guidelines or impose new limits. This often happens after new iOS technologies are made available to developers – a recent example is the banning of Notification Center utilities. However, one thing has been clear since MailWrangler’s rejection in 2008: full replacements for Apple’s system apps can’t be developed for the App Store. Developers can use the frameworks behind system features to develop third-party apps: Address Book companions, Calendar utilities, photo editing apps – these are all built using APIs and frameworks available publicly. The same has been true for browsers, which have to use Safari’s rendering engine, and alternative mail clients, which haven’t been exactly popular on the App Store, with the exception of Google’s Gmail app – an app that, however, is based on web views.

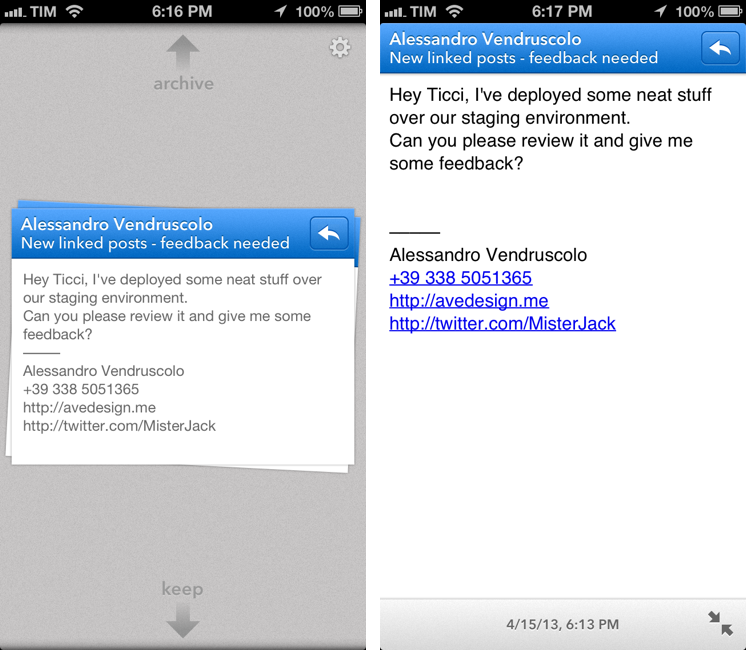

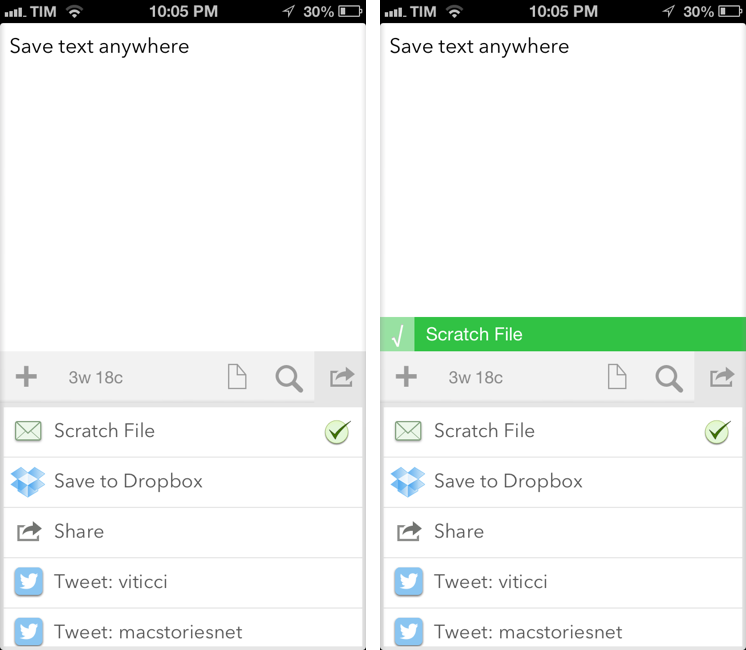

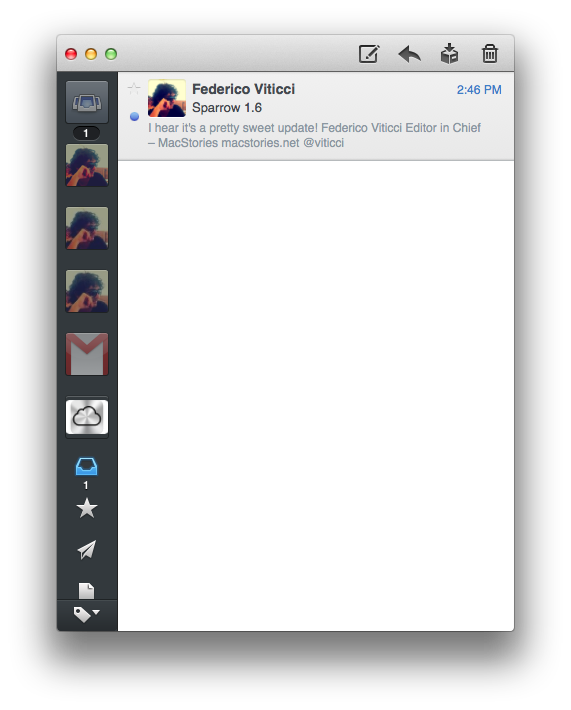

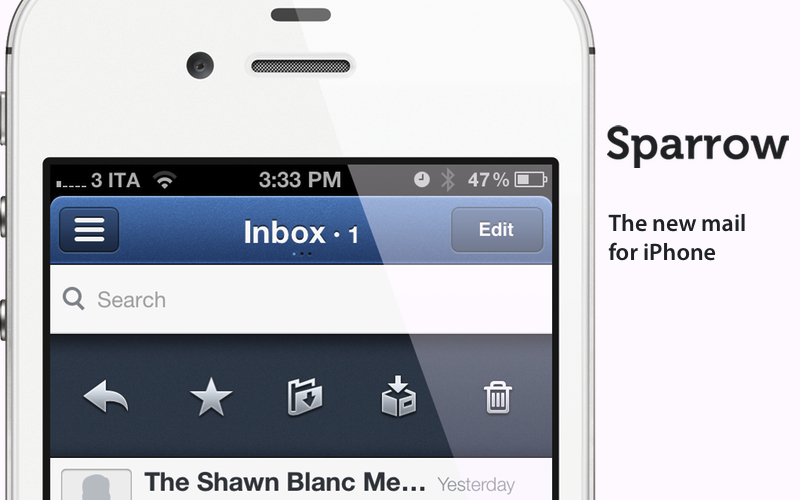

Today marks an important day in the history of the App Store. For the first time, Apple is letting a third-party developer sell a full-featured, custom email client that uses its proprietary email engine to iPhone users. Sparrow, already popular on the Mac and available on the Mac App Store, comes to the iPhone’s App Store today, and it promises to offer a newer, fresh take on email to lure back customers whose only choice since 2007 has been Apple’s Mail.app. Read more