In following the interesting debate that has arisen with the release of iBooks 2.0, iBooks Author for Mac and a EULA that doesn’t allow authors to sell iBooks outside of the iBookstore, I’ve seen two kind of reactions: it’s either a draconian move or the “obvious choice” for Apple. I think the reasoning for Apple to release iBooks Author 1.0 today lies somewhere in the middle, so I’m trying to analyze this story from Apple’s perspective, if possible.

Earlier today I tweeted:

John Gruber posted similar thoughts on Daring Fireball:

Second, it’s about not wanting iBooks Author to serve as an authoring tool for competing bookstores like Amazon’s or Google’s. The output of iBooks Author is, as far as I can tell, HTML5 — pretty much ePub 3 with whatever nonstandard liberties Apple saw fit to take in order to achieve the results they wanted. It’s not a standard format in the sense of following a spec from a standards body like the W3C, but it’s just HTML5 rendered by WebKit — not a binary blob tied to iOS or Cocoa. It may not be easy, but I don’t think it would be that much work for anyone else with an ePub reader that’s based on WebKit to add support for these iBooks textbooks. Apple is saying, “Fuck that, unless you’re giving it away for free.

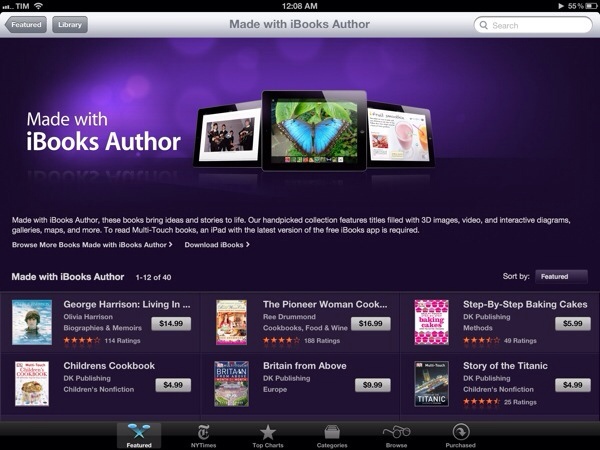

To recap: iBooks created with iBooks Author can be given away for free or sold through the iBookstore, where Apple takes a 30% cut. iBooks created with iBooks Author cannot be sold outside the iBookstore, as stated in the iBooks Author EULA

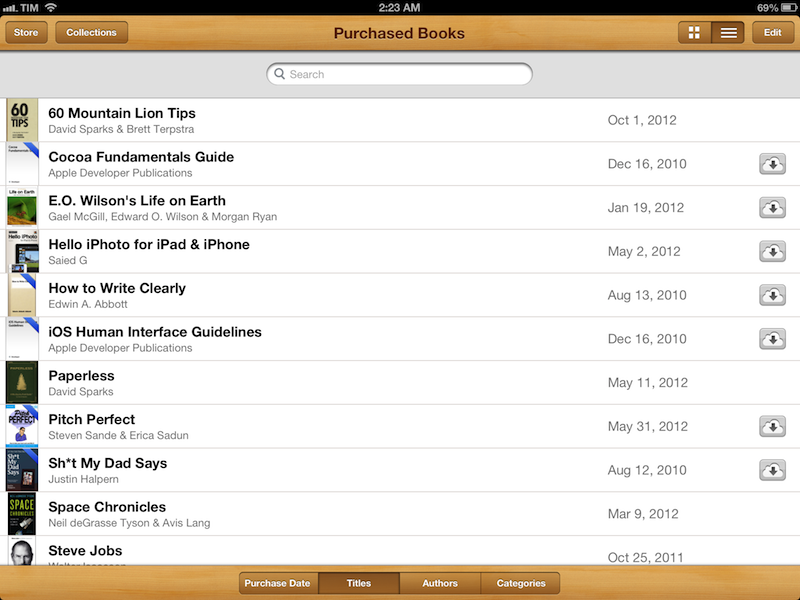

Now let’s consider the complicated scenario Apple must have faced when deciding as to whether iBooks Author 1.0 should have been a broader authoring tool, or a desktop editing suite for the iBookstore. Many devices nowadays are capable of displaying eBooks: smartphones, computers, tablets. There are several participants in the eBook race with the biggest player being Amazon, followed, I guess, by Apple with the iPad/iBookstore and many others including Barnes & Noble, Google, and so forth. eBooks are variegate: there are many file formats, different distribution networks with their own licenses and terms, different desktop editing programs that comply to a few standards, the most popular one being EPUB, which Apple also accepts for iBooks and the iBookstore. Apple is not alone in the eBook market.

Apple, however, doesn’t make much revenue off Internet services and the various Stores it operates. It’s a known fact iTunes and the App Store have been a break-even operation for many years, with the main goal of providing content and not making a serious profit. I assume the numbers for the iBookstore fall in line with iTunes and the App Store – Apple doesn’t make much money out of iBooks, nor did they ever plan to base their business on it. But: iBooks, apps and media are ways to get people to buy iOS hardware, which is where Apple makes money. Apple is a hardware company that produces fine software that helps them sell a lot of hardware. The iBookstore is, ultimately, a way for Apple to tell people that an amazing eBook reading experience is possible on iOS devices. iBooks is a brand that Apple should care to protect and maintain because it is associated with its main source of revenue – the hardware. Other companies, too, seem to understand that software and content drive hardware sales.

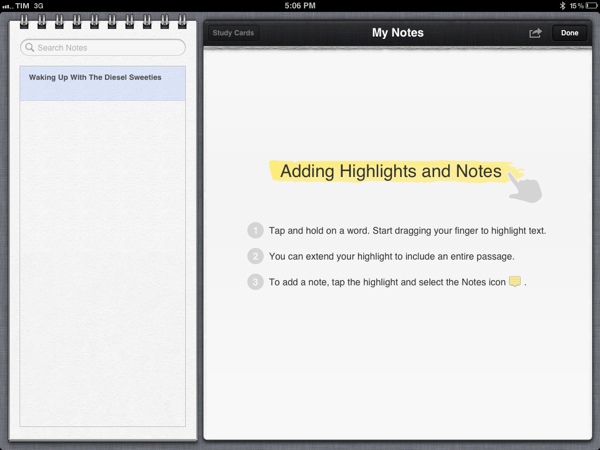

Because iBooks is Apple’s brand and platform now, Apple obviously wants to have some kind of control on the whole experience and distribution. And this is where things start to get tricky. On the App Store, apps have technical limitations that force them to go through the approval process before a user can install them. You can’t install apps in any other way, unless you’re willing to hack into your device’s operating system. Apps are made with Xcode and sold by developers enrolled in the iOS Developer Program. The setup is fairly similar with the iBookstore: iBooks are created in iBooks Author by writers/editors enrolled in the program, sold in the iBookstore so a user can download them. But there’s a big difference: we learn today that iBooks can be distributed for free elsewhere. This is not possible for iOS apps, and this is the reason I believe today’s announcement has been so controversial.

The problem, I think, is that allowing iBooks to be distributed for free anywhere but forcing authors to sell them only through Apple is seen as a pretentious move from a company that many were expecting to announce a grand plan to save the publishing industry today. It’s the sort of gray area that’s open to discussion and generally causes the sort of debates we’ve seen on the Internet. But, in fact, it is a move from a company that wants to make money: if you were to run a business you know it’s going to break even, giving away a great desktop application that costed thousands of dollars in research and development knowing that you’ll have to maintain it for years to come, wouldn’t you want to have products in your own Store and at least ask for a 30% cut?

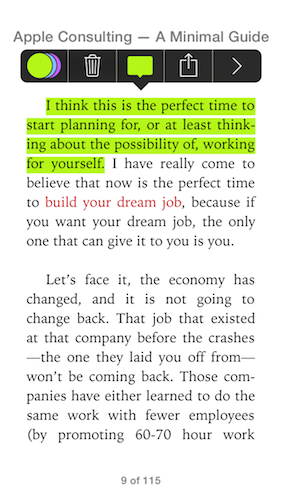

Others say the main issue is not with the 30% cut itself – we’re used to it now – it’s with the requirement of having paid editions of iBooks only in the iBookstore. It’s not like it’s technically impossible to sell them elsewhere, right? It’s not like apps – and that is correct. In theory, Apple could allow .ibooks files to become just another file format that you can distribute digitally online, and even sell it for a price as several designers do, for instance, with .psd files. But the problem lies deeper, not in the revenue cut but in the locking-in philosophy that is leading some people to believe this is akin to banning free speech. So let’s look at this from a more conceptual standpoint.

I mentioned above iBooks is a brand that is functional to Apple’s primary way of making money. Imagine this: if Apple were to allow distribution of paid eBooks anywhere, nothing could stop an author from selling it on other channels – I’d say Google and Amazon but let’s assume “his website” for now. What would stop this author from selling his iBook at a lower price on his website, and at a 30% more on the iBookstore to make up for Apple’s cut? And now with the second scenario: imagine Google rolling out support for .ibooks files in the eBookstore. Why would Apple want Google, of all companies, to get to brag about .ibooks? And even if it’s not about the .ibooks published format (of limited use outside of iBooks 2.0), why wouldn’t Apple require a small kickback for the result of a desktop program they gave you for free?

Keeping a brand, lock-in, revenue cut: it’s all part of a bigger plan, which is selling hardware people want because of the experience it provides. This experience is provided by content. Again, ecosystem.

So, in a way, iBooks aren’t too different from apps. I could even argue that in Apple’s vision, everything that goes through iTunes has some sort of exclusivity attached to it. Yes, even music and movies: iTunes Extras and LPs aren’t as popular as apps and books, but they’re an example of the integrated media/platform experience that Apple sells.

From my perspective, of course I would have been more excited to see a broader authoring tool announced today with no licensing terms for paid eBooks and full EPUB support. But as I’ve stated in a Twitter conversation with Jason Snell, this is a 1.0 version of a tool that was clearly meant for textbook publishers, and released today for other authors as well. What I could really argue is that it’s not like Apple doesn’t have the resources to come up with a full-featured authoring tool on Day One, and it would have been much better to appeal to all kinds of authors and audiences starting today with a great format and a great app. But: not all apps are perfect on day one. Not even Apple’s. Political speculation aside, I wouldn’t be surprised to know they had to get this out of the door today in preparation of the big iPad 3 launch. We’ll never know why iBooks Author was released today and not in two months with more features, but we know that Apple is a company that in the past months hasn’t been afraid of reversing a couple of unpopular decisions.

As usual, we wait.